Garth Davis, Mary Magdalene

Open your eyes to the light

“Therefore let us atone,

And become fully human,

So that the Teacher can take root in us.”

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

AS I TYPE, archaeologists are exploring newly unearthed caves on the West Bank—the site close to where a collection of ancient manuscripts known as the Dead Sea Scrolls were previously discovered—and which may similarly reveal further written documents.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, a collection of Hebrew and Aramaic parchments, first came to prominence when they were discovered in 1947 in a series of caves in Jordan, at the north-western end of the Dead Sea in the area of Khirbet Qumran. The 600 or so manuscripts, originally written on leather and papyrus, have been attributed to members of a previously unknown Jewish brotherhood, similar in nature to the Essenes. The scrolls include manuals of discipline, hymn books, apocalyptic writings and biblical commentaries.

Arguably of greater importance, however, was the discovery of a clay jar, containing 13 papyrus leather-bound books composed of 52 texts, by a peasant named Mohammad Ali two years earlier in 1945 in the village of Nag Hammadi in neighbouring Egypt. Written in Coptic (the last stage of the Egyptian language) about a millennium and a half ago, they are translations from earlier texts composed in Greek. Collectively known as the Gnostic Gospels, they bring to light the extent to which more mystical teachings existed during this period. Focusing on a diverse range of subject matter, the Gnostic Gospels include creation mythology, discussions on the nature of reality and the soul, hagiography of the apostles, issues pertaining to the divine feminine and the teachings of Jesus Christ.

Photograph: © Transmission

It is believed that the Gnostic Gospels were widely known in their day; however, their circulation was suppressed, as their nondual message was too controversial in comparison to the more conventional teachings of the Canonical Gospels in the New Testament.

Of all the Gnostic documents, the mystical vision is none so beautifully and perceptively stated as it is in the Gospel of Thomas, the very same Thomas who took Christianity to India. At the beginning of his tract, he announces the immortal phrase, “Whoever finds the explanation of these words will not taste death.” His words could be used as a preface to the entire canon of Gnostic scripture, with their focus on the annihilation of the ego into the All:

Jesus said: I am the Light that is above

them all, I am the All

attained to Me. Cleave a [piece of wood], I

am there; lift up the stone and you will

find Me there.

—Gospel of Thomas

Photograph: © Transmission

Furthermore, issues pertaining to gender, a sore subject in certain quarters of the Christian community, are irrelevant when it comes to discovering and living the Truth:

They said to Him: ‘Shall we then, being children,

enter the Kingdom?’ Jesus said to them;

‘When you make the two one, and

when you make the inner and the outer

and the outer as the inner and the above

as the below, and when

you make the male and the female into a single one,

so that the male will not be male and

the female [not] be female, when you make

eyes in the place of an eye, and a hand

in the place of a hand, and a foot in the place

of a foot, and an image in the place of an image,

then shall you enter [the Kingdom].’

—Gospel of Thomas

Echoing the immortal phrase of the Gospel of Luke, Christ proclaims that the Kingdom of Heaven is within. Interestingly, the merging of “the male and the female into a single one” resonates with Jungian psychology developed centuries later—by reconciling our respective animus and anima, the left and right cerebral hemispheres, indeed order and chaos themselves, a process of individuation and personal transformation can be achieved.

It is of no surprise, therefore, that Jesus chose to include a female apostle to follow him: the enigmatic and, until very recently, misunderstood Mary Magdalene. A great deal of myth and legend surround her; for a start, it is unclear as to whether Mary of Bethany (Lazarus’ sister), the “sinner” who anointed Jesus’ feet with oils and Mary Magdalene herself are one and the same. Moreover, in the Canonical Gospels, she is presented as being possessed of demons and evil spirits, suggesting perhaps she was of unstable mind; by 591 CE, rather dismayingly, Pope Gregory had denounced her as a prostitute.

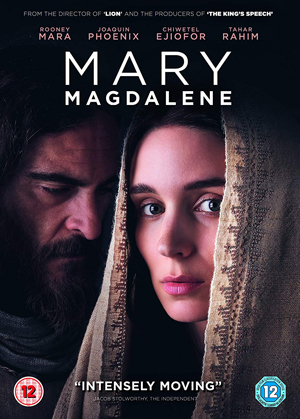

The discovery of the Gospel of Mary, however, has done much to reassert her rightful status, with her reputation further validated in the recently released movie, Mary Magdalene, exquisitely shot and acted, with Rooney Mara in the title role and Joaquin Phoenix as Jesus.

Photograph: © Transmission

In 1896, a fifth-century papyrus, written in Coptic, was bought in Cairo, which contained the text of the Gospel of Mary, together with a handful of other Gnostic manuscripts. Although not in the clay jar discovery, it is included in the Nag Hammadi library canon and known as the Berlin Codex. Whether Mary Magdalene composed the original document herself, we can only speculate.

Mary is believed to have come from Magdala on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee and was the first human being to witness the resurrected Christ. More specifically, Jesus initiated her into the mystical teachings and the knowledge that everything in the universe ultimately returns to its roots, the eternal source of all, the primordial One:

‘What is matter?

Will it last forever?’

The Teacher answered:

‘All that is born, all that is created,

all the elements of nature

are interwoven and united with each other.

All that is composed shall be decomposed;

everything returns to its roots;

matter returns to the origins of matter.

Those have ears, let them hear.

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

The opening sequence of Mary’s gospel sounds more akin to a passage from an Upanishad than a Christian text. The Teacher then goes on to speak of the nature of life and the ultimate reality of the universe. By detaching oneself from the physical world, he tells her, inner tranquillity can be found:

‘Attachment to matter

gives rise to passion against nature.

Thus trouble arises in the whole body;

this is why I tell you:

“Be in harmony …”

If you are out of balance,

take inspiration from manifestations

of your true nature.’

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

Photograph: © Transmission

Similar to Eastern teachings, the gospel purports that salvation comes from being free of all our identifications and desires. The Teacher then instructs Mary that heaven is not a place located in a future, distant land; it is present in the here and now. It is within:

‘Be vigilant and allow no one to mislead you

by saying:

“Here it is!” or

“There it is!”

For it is within you

that the Son of Man dwells.

Go to him,

for those who seek him, find him.’

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

Mary asks the Teacher how it is possible to achieve this, to find the inner Son of Man:

‘Lord, when someone meets you

in a moment of vision,

is it through the soul that they see,

or is it through the Spirit?’

The Teacher answered:

‘It is neither through the soul or the Spirit,

But the nous between the two

Which sees the vision …’

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

Nous in this context is conscious awareness (from “noumenon”); it is the universal witness, if you will, that unites the soul and Spirit into One. As the Teacher says:

There where is the nous, lies the treasure.

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

Photograph: © Transmission

In the light of the Gnostic interpretation of Jesus’ words, Christian teaching takes on a whole new meaning. Knowing, therefore, that the creation is rooted in the One, the concept of original sin becomes redundant. The Teacher declares:

‘There is no sin.

It is you who make sin exist,

when you act according to the habits

of your corrupted nature;

this is where sin lies.’

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

In other words, there is nothing inherently bad with human nature; it is the indulgence of one’s erroneous habits that is the problem and constitutes the only “sin”. (Interestingly, the original word, hamartia, generally mistranslated as “sin” actually means “missing the mark”; similarly, metanoia is not “repentance” but “turning about of the mind”.)

The Teacher then continues:

This is why the Good has come into your midst.

It acts together with the elements of your nature

so as to reunite it with its roots.

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

The Good, personified as Christ the Saviour, has, therefore, come to remove the veil of ignorance in order to reunite humankind with the One and All.

Photograph: © Transmission

The Gospel of Mary is one of the most radical and yet timeless expositions of the Truth. And yet these profound words are uttered by a woman! Indeed, Peter challenges Mary on this very point:

‘How is it possible that the Teacher talked

in this manner with a woman

about secrets of which we ourselves are ignorant?

Must we change our customs,

and listen to this woman?

Did he really choose her, and prefer her to us?’

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

But Matthew leaps to her defence:

‘Surely the Teacher knew her very well,

for he loved her more than us.’

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

Mary’s stature is further upheld in another Gnostic manuscript, the Gospel of Philip. In startling frankness, Jesus’ special relationship with Mary is made explicit:

The Lord loved Mary more than all the disciples and often used to kiss her on the mouth. When the others saw how he loved Mary, they said, ‘Why do you love her more than you love us?’ The Saviour answered them in this way: ‘How can it be that I do not love you as much as I love her?’

—Gospel of Philip

Photograph: © Transmission

There is a breathtaking scene towards the end of the film, Mary Magdalene, in which the newly arisen Christ and Mary sit together outside the city walls of Jerusalem. After telling her not to lose heart, Jesus smiles at Mary, who in turn returns his loving gaze, before they both descend into bashful laughter. It is an intensely tender moment as they sit in the majestic peace and stillness of the Judaean landscape.

As the only disciple to be at both Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, it is little wonder, therefore, that Mary Magdalene was finally given formal recognition by the Vatican in 2016 as the Apostle of the Apostles and her legacy was legitimized both through the publication of her gospel and the cinematic portrayal of her extraordinary life.

‘Henceforth I travel toward Repose,

where time rests in the Eternity of Time;

I go now into Silence.’

Having said all this, Mary became silent,

for it was in silence that the Teacher spoke to her.

—Gospel of Mary Magdalene

Post Notes

- Transmission Films

- Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love

- Teresa of Ávila: The Ecstasy of Love

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Xavier Beauvois: Of Gods and Men

- Ismaël Ferroukhi: Le Grand Voyage

- Shūsaku Endō: Silence

- Spiros Stathoulopoulos: Meteora

- Pavel Lungin: The Island

- The Cloud of Unknowing

- Michael Molinos: The Spiritual Guide