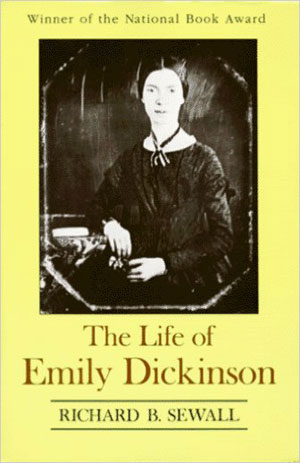

Reclusive poet who became the most celebrated poet of our time

“For love is immortality.”

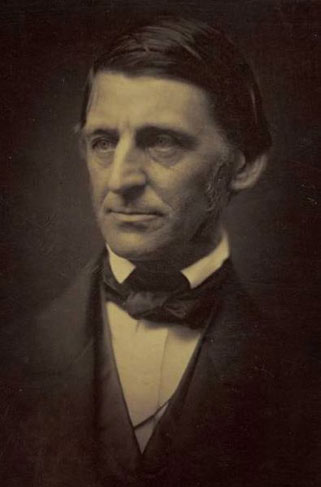

ORDINARILY, IT IS the great bastions of religion and science that lay claim to the search for discovering a unified vision of the world; however, a group of writers and thinkers would emerge in the United States, who also placed emphasis on transcendental knowledge and the belief that the soul was immanent in all creation.

Collectively known as the American Transcendentalists, the movement was a reaction to the intellectual rationalism of eighteenth-century Europe and the strict Puritan attitudes arising out of New England, brought to America by Protestant Pilgrim Fathers in the previous century.

The Transcendentalists’ chief exponent, Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), speaking of the Eternal Spirit or “Over Soul” commented that it constituted the “unity within which every man’s particular being is contained and made one with all other”.

Power of the pen

Born into this extraordinary transitional period of American history was the female poet, Emily Dickinson (10th December 1830–15th May 1886). Raised in a New England village, Amherst, her parents were respectable middle class folk with strong Calvinist roots.

Nonetheless, this was the time of the Second Great Awakening, the Puritan revival that was sweeping through New England. Unable to participate in this wave of religious fervour, she suffered an acute religious breakdown in her early childhood, which affected her for the rest of her life. She refused to associate herself with any religious domination, simply calling herself a “pagan”.

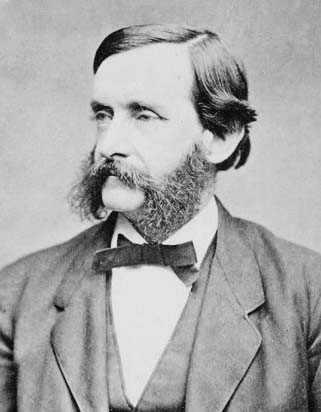

Although her calling as a poet started in her youth, Emily only started writing poetry in earnest in her late twenties. It was only then do we get a feeling of the full extent of her unhappiness and sense of isolation as a child. In 1862, she submitted four poems to the journal, Atlantic Monthly, whose editor, Colonel Thomas Wentworth Higginson, was less than enthusiastic about her verse. He found her poetry unruly and lacking any external structure. Moreover, he disliked Emily’s use of metaphor and allusion and consequently advised her to delay publication.

Photograph: [Public Domain]

Wikimedia Commons

Emily Dickinson wrote about many themes—death, Nature, romantic love. And yet despite the overt feeling of mutability and loss of the created world, there is always hope of eternal life. Like the Romanticists, her poetry is suffused with the mystical vision of a transcendental knowledge beyond all human comprehension:

I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,

And Mourners to and fro

Kept treading—treading—till it seemed

That Sense was breaking through—

And when they all were seated,

A Service, like a Drum—

Kept beating—beating—till I thought

My Mind was going numb—

And then I heard them lift a Box

And creak across my Soul

With those same Boots of Lead, again,

Then Space—began to toll,

As all the Heavens were a Bell,

And Being, but an Ear,

And I, and Silence, some strange Race

Wrecked, solitary, here—

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down—

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And finished knowing—then—

And then? The poet is poignantly silent.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Death of self

The annihilation of the self is a theme Emily returns to time and again:

Me and Myself—to banish—

Had I Art—

Impregnable my Fortress

Unto All Heart—

But since Myself—assault Me—

How have I peace

Except by subjugating

Consciousness?

And since We’re mutual Monarch

How this be

Except by Abdication—

Me—of Me?

The mistress of metaphor, Emily employs many images to represent her abstract ideas. As well as being aligned with the Transcendentalists, she has often been compared to the Metaphysical Poets, owing to her brevity of expression and use of complex conceits.

Photograph: Southworth & Hawes,

[Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

I cross till I am weary

A Mountain—in my mind—

More Mountains—then a Sea—

More Seas—And then

A Desert—find—

And My Horizon blocks

With steady—drifting—Grains

Of unconjectured quantity—

As Asiatic Rains

Not this—defeat my Pace—

It hinder from the West

But as an Enemy’s Salute

One hurrying to Rest—

What merit had the Goal—

Except there intervene

Faint Doubt—and far Competitor—

To jeopardize the Gain?

At last—the Grace in sight—

I shout unto my Feet—

I offer them the Whole of Heaven

The instant that we meet—

They strive—and yet delay—

They perish—Do we die—

Or is this Death’s Experiment—

Reversed—in Victory?

The feminine mystique

Despite the literary freedom Emily Dickinson enjoyed in her poems, she was, however, subjugated to the prevailing nineteenth-century ideology regarding women, and in particular, ideas regarding whether or not a female poet should be published.

Emily was inconsistent on the issue, believing on the one hand equal rights should exist for both male and female artists, whereas on the other, she shied away from fame—in her own lifetime, she only published ten poems. It was only until after her death in 1886 of Bright’s disease that her vast corpus of work—1,775 short lyrics—was discovered, stitched into in packets known as fascicles, accumulated in a bureau drawer. It was her publisher, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who was left the main responsibility of editing and publishing her work.

As Emily grew older, she shunned the outside world more and more. Indeed her reclusive behaviour even saw her closest friends refused entry into the family home. Various myths have arisen to describe such a stance—agoraphobia; a literary “pose” enabling her to write; an unrequited love.

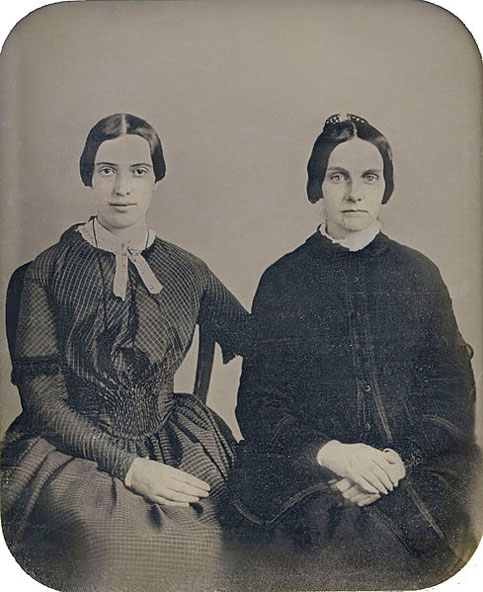

The only verified black and white photograph of Emily shows a thin, gaunt-faced young woman, with serious dark eyes, betraying no hint of emotion—a façade, perhaps, to the swathe of feeling beneath. Interestingly, however, in September 2012, the Amherst College Archives and Special Collections unveiled a new daguerreotype, proposing it to be Dickinson and her friend Kate Scott Turner (ca. 1859), though it has yet to be authenticated.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

The Master Letters

Despite the fact that Emily was perceived as being ambivalent to marriage and resenting the restraint it placed on a woman’s freedom, three draft letters were discovered after her death that deal with the nature of love. Collectively known as the Master Letters, they are directed to an unidentified lover and are the intimate confessions of her heart.

Some commentators have suggested suitable candidates, both single and married, male and female, the most notable being Susan Dickinson, her sister-in-law and poet in her own right (some feminist critics have identified a thread of homoeroticism in Emily’s verse).

Whomever the intended recipient, they reveal a side to Emily not prevalent in her poetry. In the three letters, the power of her emotion and heart-felt longing is breathtakingly moving. It is the second letter, however, which is unashamedly urgent and direct in its confession of her romantic feelings:

MASTER,

… I am older—tonight, Master—but the love is the same—so are the moon and the crescent. If it had been God’s will that I might breathe where you breathed—and find the place—myself—at night—if I [can] never forget that I am not with you—and that sorrow and frost are nearer than I …

Emily fantasizes about a possible relationship with the Master but there is an undertone of doom, of hope fading into the unrequited reality of her love. The letter can in fact be read as a microcosm of Emily’s life and her friendships with others. Not only did she remain single, she had not one sustaining relationship, Platonic or otherwise. It is said that such was the intensity of her personality, both intellectually and emotionally, that any possible friends or suitors simply shied away.

As with so many women who composed verse and prose with a radically unique style and meaning, she has only come to be appreciated after her death. And yet, like her male contemporary, Walt Whitman (1819-1892), whose immortal lines, “I celebrate myself, and sing myself”, in his poem, Song of Myself, inspired generations of mystical poets, so too do the haunting lines of Emily Dickinson:

Behind Me—dips Eternity—

Before Me—Immortality—

Myself—the Term between—

Death but the Drift of Eastern Gray,

Dissolving into Dawn away,

Before the West begin—

‘Tis Kingdom—afterward—they say—

In perfect—pauseless Monarchy—

Whose Prince—is Son of None—

Himself —His Dateless Dynasty—

Himself—Himself diversify—

In duplicate Divine—

‘Tis Miracle before Me—then—

‘Tis Miracle behind—between—

A Crescent in the Sea—

With midnight to the North of Her—

And Midnight to the South of Her—

And Maelstrom—in the Sky—

Post Notes

- Emily Dickinson Museum

- Dickinson Electronic Archives

- Emily Dickinson Archive

- Amherst College Archives and Special Collections

- Sappho: The Tenth Muse

- Matsuo Bashō: Deep Silence

- Roger Housden: Ten Poems for Difficult Times

- Liam Ó Muirthile: Camino de Santiago, Dánta, Poems, Poemas

- Archana Bahadur Zutshi: Poetic Candour