The triumph of experience over knowledge

“Only connect.”

WHEN I WAS an undergraduate at London University, the movie production team, Merchant Ivory, came to our college, Royal Holloway, to film sequences for their film adaption of E. M. Forster’s Howards End.

It was a glorious time, not least because our humble academic institution had been turned into a film set bustling with famous actors costumed in Edwardian glamour but also the fact that one of my favourite authors was being brought to the silver screen.

All the novels of E. M. Forster (1st January 1879–7th June 1970) are literary classics in their own right along with Howards End—A Room with a View, A Passage to India, Maurice, Where Angels Fear to Tread, to name the most distinguished. Indeed, writing during a time of increasing technological advances and mechanization, marked by two world wars, Forster became a leading exponent championing the rights of the individual, the importance of the inner being and the value of personal freedom.

His short stories are lesser known but exhibit similar themes, “The Celestial Omnibus” being the most perfectly formed fable in its examination of the triumph of childhood innocence and wonder over literary snobbery and intellectual pretence. Reminiscent of Peter Pan and Alice in Wonderland, it is a supernatural tale of an unnamed boy with a healthy thirst for the imagination and life. Upon finding a blind alley opposite his home in Surbiton, marked by a signpost that simply reads, “To Heaven”, he thus embarks on an adventure of the profoundest kind, a journey that will take him to the very realm of the gods.

Piqued by his stuffy, middle-class parents’ dismissal of his discovery, he ventures out onto the twilight street to investigate the curious alleyway once and for all. Just as Percy Bysshe Shelley was seduced by the evening carolling of a skylark, the boy is beckoned towards something to which he feels inextricably drawn:

… at the present moment the whole road looked rather pretty, for the sun had just set in splendour, and the inequalities of rent were drowned in a saffron afterglow. Small birds twittered and the breadwinners’ train shrieked musically down through the cutting—that wonderful cutting which was drawn to itself the whole beauty out of Surbiton, and clad itself, like any Alpine valley, with the glory of the fir and the silver birch and the primrose. It was this cutting that first stirred desires within the boy—desires for something just a little different, he knew not what, desires that would return whenever things were sunlit, as they were this evening, running up and down inside him, up and down, up and down, till he would feel quite unusual all over, and as likely not would want to cry.

Exhilarated by the stirring for adventure, he tentatively enters the alley. By contrast, it proves to be empty, dank and claustrophobic and yet an enigmatic timetable is plastered to the wall, indicating the schedule of the “Sunrise and Sunset Omnibuses”, with their extra inducement of “Return Tickets!”

Oscillating between scepticism and longing, the boy decides to return the following morning at the break of dawn to determine whether the whole thing is an elaborate hoax. And thus, his fate is irrevocably sealed:

But the omnibus was there … It had two horses, whose sides were still smoking from their journey, and its two great lamps shone through the fog against the alley’s walls, changing their cobwebs and moss into tissues of fairyland.

The driver of the barouche is Sir Thomas Browne, seventeenth-century physician and freethinker, though the boy is unaware of his importance. Invited to join him up on the driver’s box, he proceeds to ask the man of his profession:

‘As a healer of bodies, I had scant success … But as a healer of the spirit I have succeeded beyond my hopes and my deserts. For though my draughts were not better nor subtler than those of other men, yet, by reason, of the cunning goblets wherein I offered them, the queasy soul was ofttimes tempted to sip and be refreshed.’

‘The queasy soul,’ [the boy] murmured; ‘if the sun sets with trees in front of it, and you suddenly come strange all over, is that a queasy soul?’

‘You have felt that?’

‘Why yes.’

Feeling a natural affinity with his new friend and driver that he has never experienced before with other adults, they ascend over London through the fog for well over two hours. Then suddenly, they are enveloped by thunder and lightning, which dissipate into a magnificent rainbow-bridge extending all the way towards Heaven.

‘But how beautiful! What colours! Where will it stop? It is more like the rainbows you can tread on. More like dreams.’

In a vision recalling an enactment of Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, a wondrous landscape unfolds before them, including a river, in which maidens are singing and playing with a golden ring. Indeed, the entire universe is resounding to the tune of the Rhinemaidens’ song.

Needless to say, the boy’s parents are unsympathetic to his tales of “Neverland” upon his return to his dreary, bourgeois existence and he is punished with caning and the memorizing of a passage from the poetry of Keats.

A visiting neighbour, Mr Septimus Bons, President of the Literary Society and an intellectual snob (“Bons”, despite overtly meaning “good”, is in fact “snob” spelt backwards), is perversely intrigued by the boy’s celestial adventure. He agrees to accompany him to the alley the following evening at sunset in order to verify for himself the mysterious story of the omnibus.

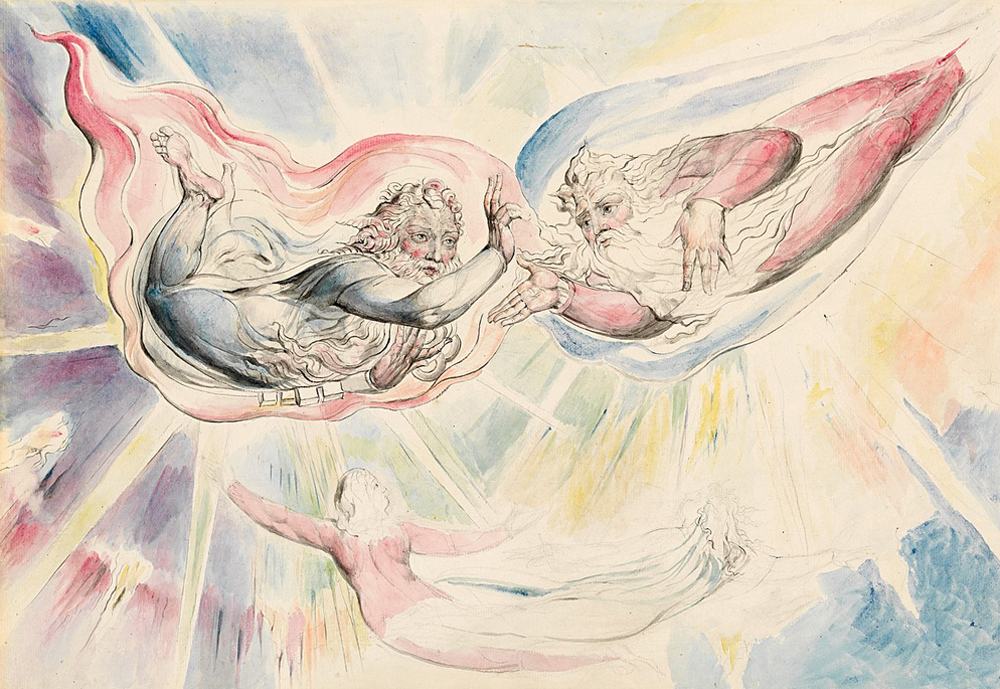

To his utter astonishment, Mr Bons witnesses the arrival of the barouche. This time, the driver is none other than Dante Alighieri, made explicit from the emended quotation from Inferno, which is placed above the carriage door:

‘Lasciate ogni baldanza voi che entrate’

(‘Abandon all self-importance, you who enter here’)

Characteristically, Mr Bons points out that “baldanza” is obviously an error, and that it should, in fact, read “speranza” (“hope”). Being a literary scholar, he cannot tolerate any form of deviation or inexactitude when it comes to the appreciation of the Greats, though sadly the irony is wasted on the self-righteous pedant.

As they take flight over the city, the boy, who is utterly in awe of his fellow traveller, innocently recounts the pantheon of literary and classical immortals he met on his previous trip. And yet his naive ebullience only serves to irritate Mr Bons all the more, who continues to correct all his historical errors.

When the rainbow materializes once again beneath the carriage, the boy is positively ecstatic at the sight of the hero, Archilles, who is standing sentry on the bridge. Mr Bons, however, is terrified by the personification of the Greek warrior. He demands of the driver to take him home, back to the comfort of his suburban library with its secondhand knowledge, rather than be party to this extraordinary and overwhelming experience:

‘Save me! … I have honoured you. I have quoted you. I have bound you in vellum. Take me back to my world.

Dante Alighieri, however, is unimpressed:

‘I am the means and not the end. I am the food and not the life. Stand by yourself, as that boy has stood. I cannot save you. For poetry is spirit; and they that would worship it must worship in spirit and in truth.’

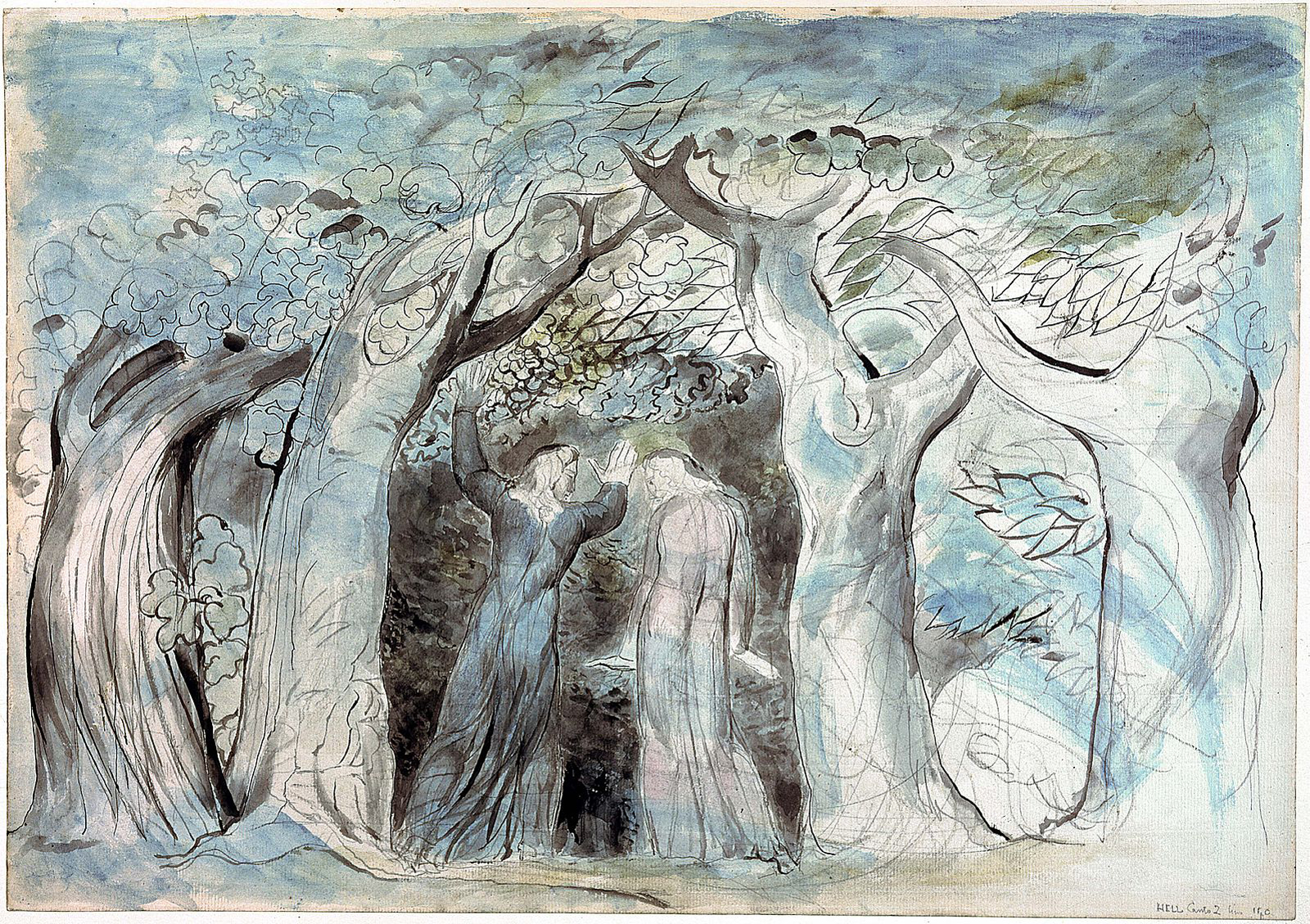

William Blake, St Peter and St James With Dante and Beatrice.

Image: Public Domain

It is quite literally the end of the road for the consummate dilettante, Mr Bons. As his nemesis befalls him, the boy is crowned with leaves by the gods.

Forever the supreme storyteller, Forster points us to the perils of any form of intellectual arrogance and academic pedantry, and the price that must be paid—the death of integrity, authenticity, one’s very own inner soul—advocating instead a love of poetry and literature, indeed all the Creative Arts, for their own pleasurable sake.

In our contemporary digital world, in which pseudo-intellectuals and literary pundits are pontificating their ideas all over the internet, E. M. Forster’s elegant masterpiece is a prophetic gem.

Post Notes

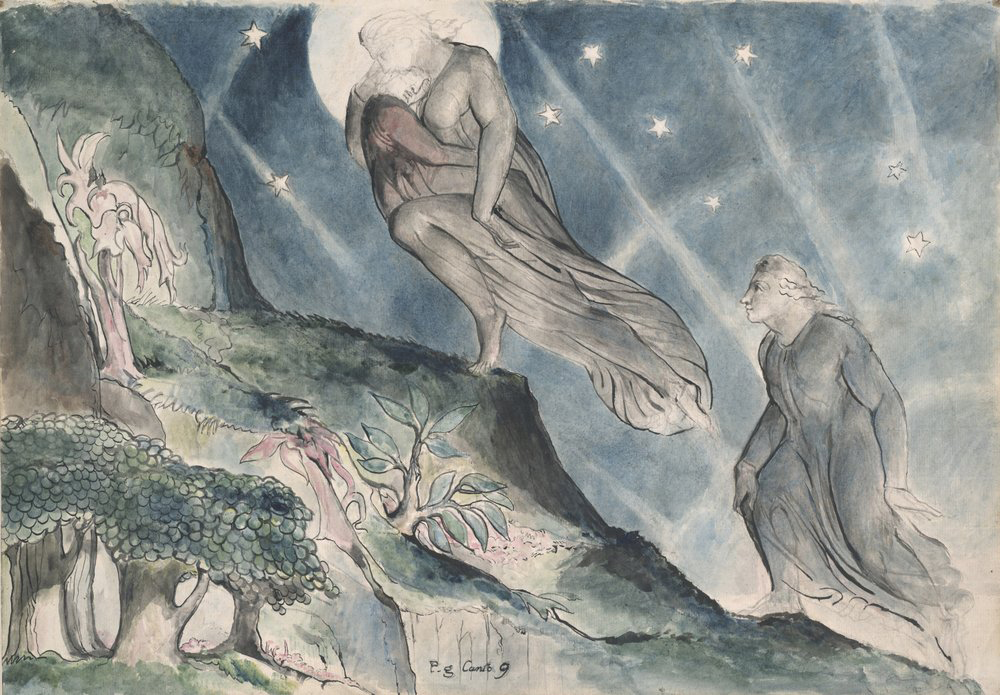

- Feature image: William Blake, Dante and Virgil Penetrating the Forest, Public Domain

- Merchant Ivory Productions

- Jack Kerouac: Alone on a Mountaintop

- Writers & Artists Spirituality Series

- Leo Tolstoy: The Three Hermits

- Hermann Hesse: The Journey to the East

- Matsuo Bashō: The Narrow Road to the Deep North

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: The Over-Soul

- Rollo May: My Quest for Beauty

- Alan Watts: Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme