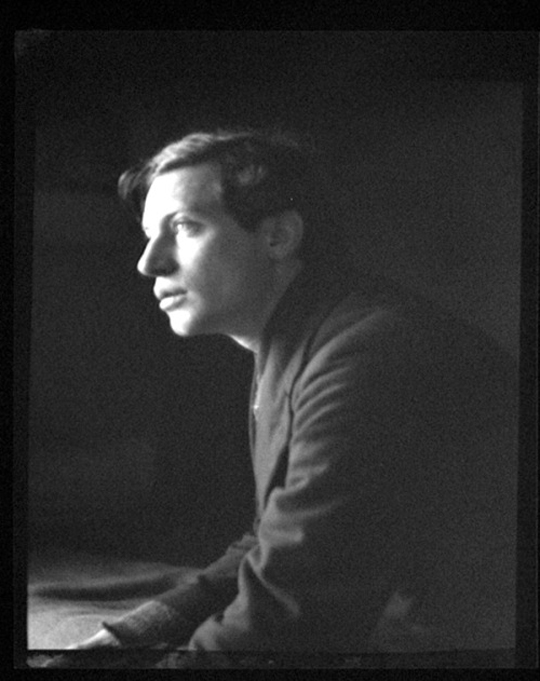

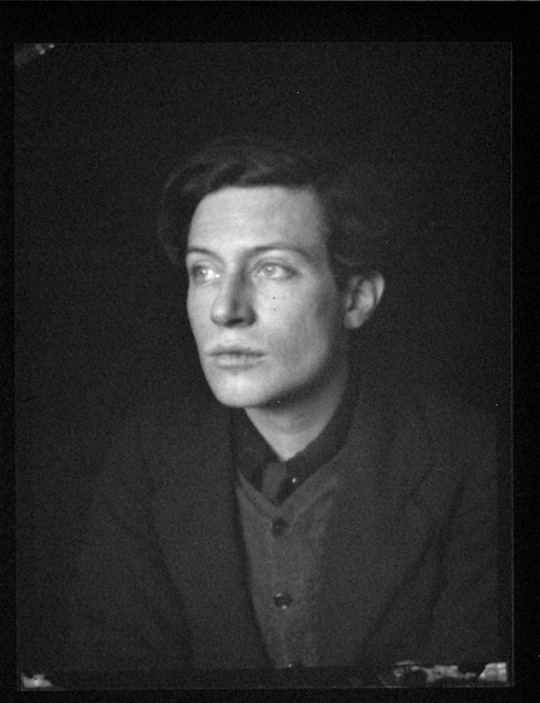

Photograph: © Estate of Duncan Grant. All rights reserved, DACS 2018

The Light of All Lights

All things were made by Him; and without Him was not anything made that was made.

In Him was life; and the life was the light of men.

And the light shineth in the darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not …

That was the true Light, which lighteth every man that cometh into the world.

He was in the world and the world was made by Him, and the world knew him not …

And the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us … full of grace and truth.

—John 1:3-5, 9-10, 14

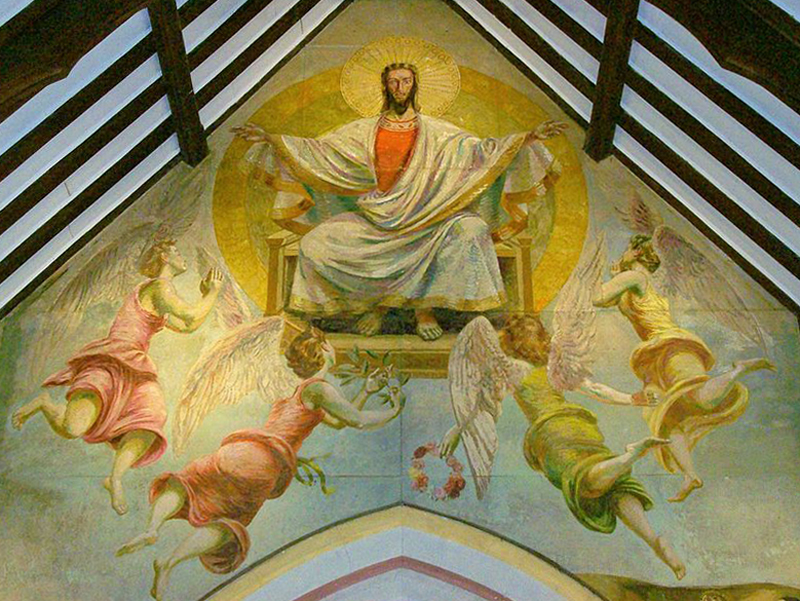

I AM sitting in the final pew of Berwick Church. I am alone and as I look up above the chancel towards Duncan Grant’s Christ in Glory, I feel somewhat disappointed. Ominous shadows bleed from the rafters, drenching the Saviour’s form in darkness and gloom.

Behind me, I hear the click of the main door latch and I sense the presence of another. And then a female voice, empathic and gentle, whispers: “Do you want me to turn on the light?” Suddenly, the nave is bathed in radiant luminosity and the gloriousness of Jesus and his angels manifest before me … and I gasp.

How to describe in words the overwhelming feeling of bearing witness to one of the most beautiful religious artworks I have ever seen? As I meet Christ’s eyes, Calvary-sky blue, I realize I am also looking into the very face of Duncan Grant himself.

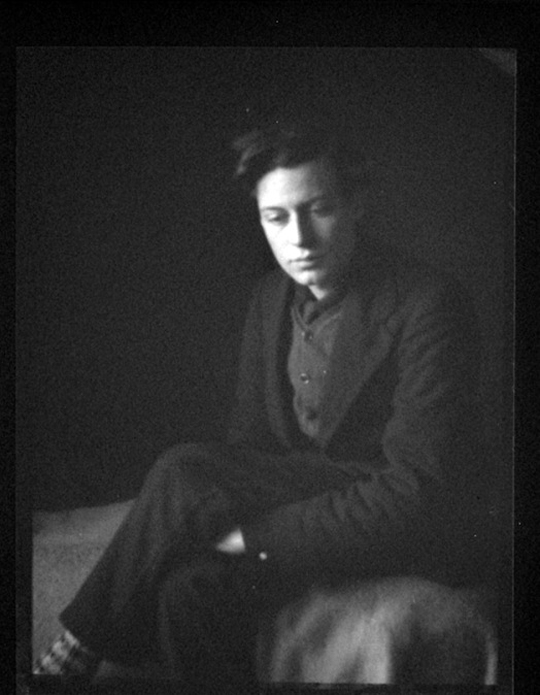

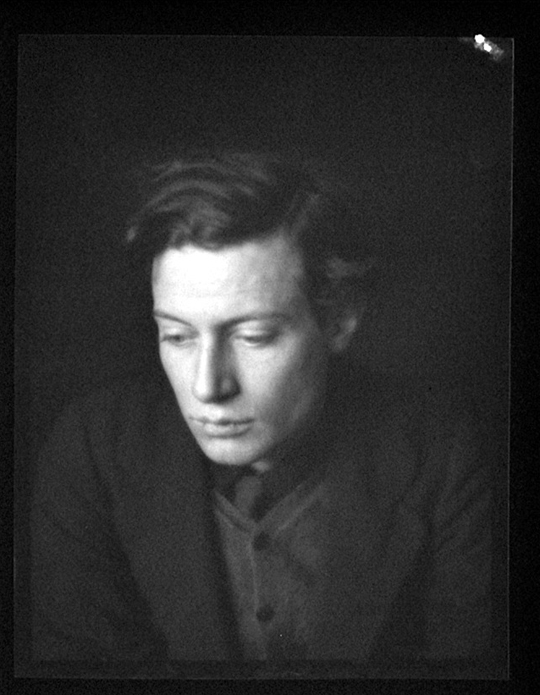

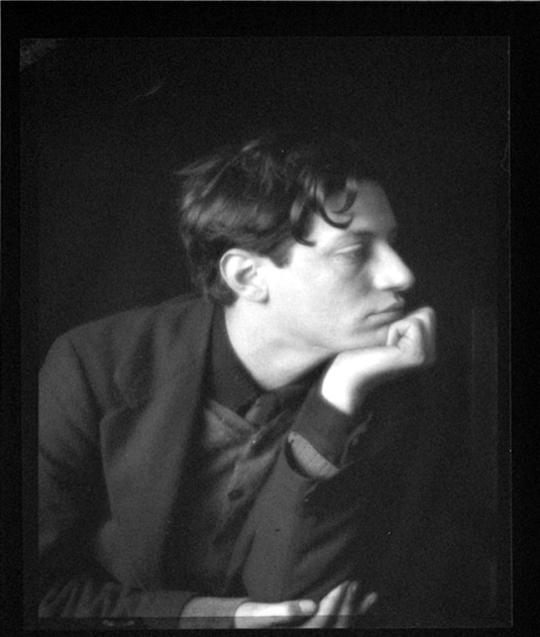

Photograph: Public Domain

In November 1939, World War II already unleashed on Europe only two months earlier, George Bell, Bishop of Chichester from 1929 until 1958, sat down and wrote a preliminary draft paper entitled, “Artists and the Church in War Time”, outlining his thoughts on the role of art in a society traumatized by conflict. An artist in his own right—a poet—he intuitively understood the way in which the religious life of a community could be linked with the creative spirit of contemporary art, the Church itself being a natural environment for the expression of mystical experience:

… Artists are exceptionally hard hit by the war. And yet it is more important than ever to keep the arts alive, with all that they represent, in times like these. In days not less unsettled long ago, the Church offered all manner of opportunities to the Artist—the sculptor, the painter, the craftsman as well as the architect. The evidence of their genius and their skill is to be found in the Churches and the Cathedrals all over England. Could not the Church, as part of its sense of inestimable value of spiritual things, renew its association with the Artists of different kinds today? By such a re-association it would do much, not only for the Artists but for the community as a whole. What is needed is a lead. It is important to begin. Even small beginnings help, and small beginnings may well point the way to larger efforts.

Photograph: Public Domain

Moreover, drawing on the sentiments of T. S. Eliot’s “Notes Towards the Definition of Culture” in which the Modernist poet states that “the culture of Europe could not survive the complete disappearance of the Christian faith … If Christianity goes, the whole of our culture goes,” Bishop Bell was only too acutely aware that in allowing contemporaneous artists to decorate Berwick Church, he was preserving, in essence, the very foundation of Western civilization itself. Speaking at a conference in 1944 entitled “The Church and the Arts” at his episcopal seat in Chichester after the completion of the first phase of paintings, Bishop Bell expressed his passionate belief:

It is a commonplace that we are living now in the midst of a great spiritual crisis. I believe that the Church and the Artist together have a big contribution to make to mankind, not least England, in relation to it. What we all need, what the world needs, is Order, a Pattern, a sense of purpose, a Philosophy, a Faith. The Church as a Faith and the Artist with his vision has the genius and the capacity to meditate Order and to represent the Faith. Certainly, the Church needs the Arts very badly … I want to see Art playing a much larger part in people’s lives and I also want to see religion making a much larger contribution to the tradition and atmosphere in which people live.

Photograph: Public Domain

And thus, Duncan Grant, together with Vanessa Bell (sister to Virginia Woolf and no relation to Bishop Bell) and Quentin Bell (son of Vanessa), were all commissioned by the Bishop to paint the interior walls of Berwick Church, an ancient rural parish church dating back to the eleventh/twelfth century situated in East Sussex in the south-east of England.

Despite the fact that both Duncan, Vanessa and Quentin were all atheists, they threw themselves wholeheartedly into the project, producing a fusion of traditional and contemporaneous artistic scenes from nature—the Four Seasons and the Pulpit panels—as well as the Scriptures—the Nativity, the Annunciation, the Sacraments—with Vanessa declaring, “… on the whole we accept every suggestion and read our Bibles diligently.” Indeed, in a sermon in October 1943 to commemorate the progress of the work, Bishop Bell remarked that the paintings were a “call to worship—a call to adore”.

Photograph: Public Domain

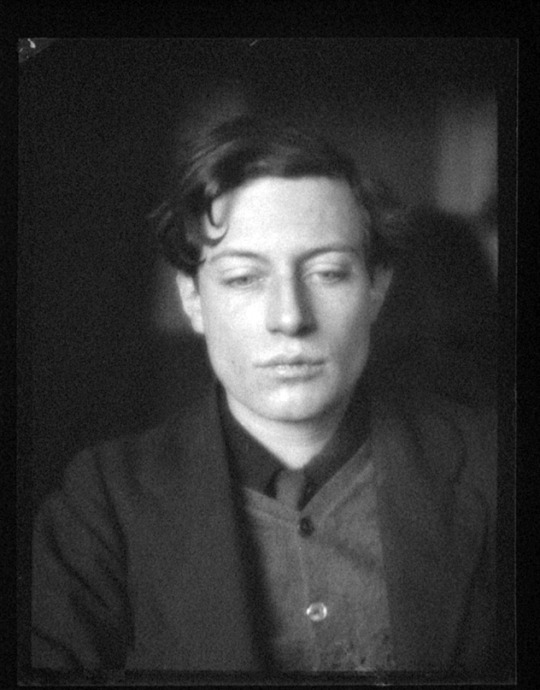

The three Bloomsbury artists contributed in their own unique way to the decorative scheme of Berwick Church and yet it is Duncan Grant (21st January 1885–8th May 1978), as lead artist, who captures my attention the most. An only child born in Scotland, he spent his formative years growing up in India and Burma where his father served as an army officer, returning at the age of nine to board at Rugby School, where his art teacher introduced him to the work of Pre-Raphaelite painter, Edward Burne-Jones. And yet, it would be after his confirmation and while a student at the Westminster School of Art that Duncan appears to have had a profound mystical encounter:

I was painting with orange, yellow and crimson. I was working from the window of my small bedroom looking down the village street of Streatleigh on Thames in Berkshire. I must have reached the age of 17 … I remember having a sort of visionary experience, I can only call it that because it had a curiously objective outside-of-myself sort of character. ‘You must go out into the world,’ my inner voice said, ‘and learn all that there is to know and be seen in the world of painting. The impressionists you must see and learn from and then there are other things going on at this very moment of which you know nothing.’ I realized that all this was true and made up my mind to follow the advice of this inner voice.

Photograph: Public Domain

The inner voice would eventually lead Duncan to execute one of the most outstanding paintings of his entire artistic career, Christ in Glory, which forms the centrepiece of Berwick Church. No doubt, he would have taken inspiration from his days in India and the rich, exotic colours that dominate Asian painting. He would have also been acquainted with the patterns and geometric shapes of Asian art, which are a means of enabling spiritual contemplation—indeed, the upper design of Christ in Glory is centred around a yellow circle with radiating arcs in a manner similar to a Buddhist mandala, a visionary blaze of celestial triumph.

Similarly, in the spirit of the Eastern Orthodox Church, icons are considered to have sacramental power, facilitating oneness with the divine and communion with a deeper collective unconscious. The head of Duncan’s Christ clearly displays similarities to Byzantine iconography, with the enlarged forehead denoting a heightened intellectual capacity, which in the Eastern Christian tradition is given supreme importance over and above all other aspects of the human psyche, rendering him the personification of wisdom.

Photograph: Public Domain

Christ in Glory is quite simply beautiful. I could gaze at it for hours, lost in the Saviour’s outstretched golden arms, his regard acting as a centripetal force, mesmerizing me with the power of his eyes. As the rest of the corporeal world is turning about him, time stops as I connect with the omnipresent soul of the universe and the cosmic still point at the centre of all created things.

Akin to Matisse’s La Danse, the angels move in graceful, excited motion at his feet in a state of ecstatic bliss and gravitational suspension. I feel almost giddy from the orbital movement and energy of Duncan’s compositional piece. This is in distinct opposition to the static figures, standing as sentinels, at the bottom of the mural, rooted in the temporal world and contextualizing the painting overall, with references to World War II as well as portraits of the then rector of Berwick Church, Revd George Mitchell, and Bishop Bell. The chancel arch and screen similarly enhance the boundary between the secular world and the transcendental realm.

Photograph: Public Domain

The ambiance of Berwick Church is of a Renaissance chapel bathed in Mediterranean sunshine. Despite its small scale size, there is a sense of spaciousness to the interior making me feel deeply at ease as I am inextricably transported to another clime and rejuvenated by the aesthetic shift. Indeed the inclusion of trompe l’oeil windows further enhances an otherworldly quality to the overall schema, the circularity of their openings offering a portal to eternal peace and emptiness beyond.

As the French philosopher and mystic, Simone Weil, wrote in her seminal, Gravity and Grace, and the need to create space in which the divine spirit can penetrate: “Grace fills empty spaces but it can only enter where there is a void to receive it and it is grace itself which makes this void.”

Photograph: Public Domain

I step outside of the church. To the south of the churchyard, through a gap in the trees, is a solitary bench, idyllically positioned to imbibe the breathtaking panoramic view of the Downs escarpment from Windover Hill in the east towards Firle Beacon in the west. It is a brilliant sunny day and the painterly prospect renders me overwhelmed by the sheer visual beauty of nature’s palette similarly captured by the Bloomsbury artists—yellow rape, blue sky, green fields.

As my heart opens out to the Arcadian vision cast before me, the pain of unconscious wounds rises up to the surface of my being and long, hot tears are suddenly streaming down my cheeks. Rather than wipe them away and cover my shame under a handkerchief, I let my eyes surge and swell to the rhythm of the emotional tide coursing through my body and veins.

Photograph: Public Domain

I become conscious of my mortality, that if I have three score years and ten years to walk this earth, I only have a couple of decades remaining and feel that I am far from ready to leave this blessed life. How I so want to accomplish a myriad of artistic projects of my own, develop a meaningful spiritual practice … and suddenly I am consumed by regret, self-pity and remorse.

And then a voice from the catacombs of my subconscious calls unto me, a quotation from the Book of John: “I have come into the world as light so that whoever believes in Me may not remain in darkness” (12:46). An apparition of the Saviour’s face as tangible as Christ in Glory itself suddenly rises up before me. A syzygy of spirituality and art. I close my eyes and drink deeply of his loving gaze, abandoning myself to a life that is unfolding simply as it is, and his ocular luminescence and I become one.

Photograph: Public Domain

oOo

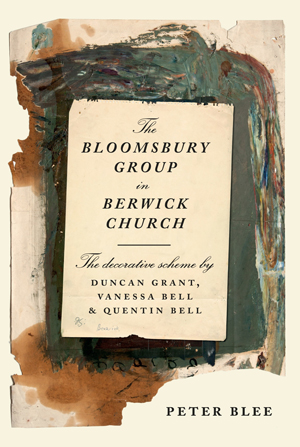

Peter Blee, Rector of St Michael and All Angels, Berwick together with the neighbouring churches of Alciston, Arlington, Selmeston and Wilmington, is the author of a stunning monograph on the cultural context and decorative scheme of the Berwick murals, entitled The Bloomsbury Group in Berwick Church, which provided the research material for the above article.

He is also currently engaged in a project to raise £950,000 in donations in order to conserve the paintings and stabilize their environment for the future, whilst developing the church’s vision of working creatively with small groups of vulnerable and disadvantaged individuals.

If you would like more information about the Berwick (Sussex) Conservation Trust or even feel inspired to consider offering a financial gift towards the conservation project, you can either download a brochure or else visit the Berwick Church website.

Post Notes

- St Michael and All Angels, Berwick Church website

- Charleston

- Monk’s House, National Trust

- Jean Cocteau: Chapelle Saint-Pierre de Villefranche-sur-Mer

- Paula Marvelly: Sacra di San Michele

- Henri Matisse: Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence

- Paula Marvelly: Sanctuaire Notre-Dame de Laghet

- Krishnamurti’s Notebook

- Marc Chagall: All Saints’ Tudeley