Garden Museum, Howard Sooley: Prospect Cottage

An open door to soul

“Busie old foole, unruly Sunne,

Why dost thou thus,

Through windows, and through curtaines call on us?

Must to thy motions lovers’ seasons run?

Sawcy pedantique wretch, goe chide

Late schoole boyes and sowre prentices,

Goe tell Court-huntsmen, that the King will ride,

Call countrey ants to harvest offices;

Love, all alike, no season knowes, nor clyme,

Nor houres, dayes, moneths, which are the rags of time …

Thou sunne art halfe as happy as wee,

In that the world’s contracted thus.

Thine age askes ease, and since thy duties bee

To warme the world, that’s done in warming us.

Shine here to us, and thou art every where;

This bed thy centre is, these walls thy spheare.”

—John Donne, “The Sunne Rising”

DRIVING TO PROSPECT COTTAGE from Sussex through verdant, tree-lined lanes is something of a shock as one turns into the Dungeness Estate on the spit of the coast of Kent. An unfolding landscape of alien, minimalist beauty shrouded in a diaphanous azure haze provokes the opening lines of Derek Jarman’s last feature film, Blue, to arise in mind: “Oh blue, come forth; oh blue, arise; oh blue, ascend; oh blue, come in!”

Despite being the beginning of autumn, the landscape is saturated in sunshine as I crunch my way over shingle to the home of British painter, theatre designer, filmmaker, poet, gay rights activist and gardener Derek Jarman (31st January 1942–19th February 1994), where he lived during the final eight years of his life before dying from an AIDS-related illness.

Nearly 30 years after his death, Prospect Cottage remains a site of pilgrimage for people from all over the world who come to be inspired by Jarman’s artistic legacy, yet it is only recently that one can actually go inside and witness his private sanctuary firsthand. Thanks to Keith Collins (1966–2018), Jarman’s close companion in his final years to whom he bequeathed Prospect Cottage, Creative Folkestone has been entrusted with the custodial initiative of allowing the right to public access, with ongoing financial patronage from the Art Fund, Tate and other private sponsors.

When I came to Dungeness in the mid-eighties, I had no thought of building a garden. It looked impossible: shingle with no soil supported a sparse vegetation. Outside the front door a bed had been built—a rockery of broken bricks and concrete: it fitted well. One day, walking on the beach at low tide, I noticed a magnificent flint. I brought it back and pulled out one of the bricks. Soon I had replaced all the rubble with flints. They were hard to find, but after a storm a few more would appear. The bed looked great, like dragon’s teeth—white and grey. My journey to the sea each morning had purpose.

I decided to stop there; after all, the bleakness of Prospect Cottage was what had made me fall in love with it. At the back I planted a dog rose. Then I found a curious piece of driftwood and used this, and one of the necklaces of holey stones on the wall, to stake the rose.

The garden had begun.

I saw it as a therapy and a pharmacopoeia.

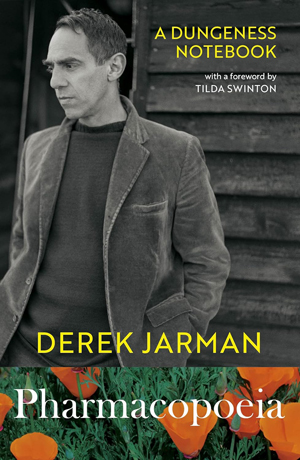

—Derek Jarman, Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook

A charming anecdote, outlined in his journals, tells of the purchase of Prospect Cottage. In 1986, on a spring afternoon drive through Kent looking for bluebell woods to use as a location for his forthcoming feature, The Garden, starring Tilda Swinton, Jarman suggested to Keith Collins that they should eat at the Pilot Inn, Dungeness, renowned for serving “simply the finest fish and chips in all England”.

Deciding to visit the lighthouse afterwards, Jarman mentioned that there was a beautiful fisherman’s cottage en route and should it ever be for sale, he would probably offer to buy it. Nearing the modest Victorian abode, with its black-tarred silhouette checkered with yellow door and window frames, they noticed the “For Sale” sign hanging provocatively outside, the sheer improbability of the coincidence making the purchase inevitable.

Prospect Cottage subsequently became a source of inspiration and creative hub for Jarman, together with his friends and fellow collaborators, devoting his time and energy to his multidisciplinary practices—filmmaking, art, writing and gardening.

The summer is over. The corn harvested. The fields are ploughed. The ploughman wears chocolate brown corduroy. Brown is the colour of riches. The man who owns acres is a rich man, both in pocket and hopefully in soul. For the soul is deep … a peaceful brown. However much you possess in life, even if your land stretches beyond the horizon, in death you will end up with six foot.

The woods and hedgerows turn the innumerable shades of brown from yellow to red. I ran back and forth in the dying light of October; catching the gold-brown leaves as they fell from the chestnut trees before they touched the earth and were swept up into the bonfire. Each leaf caught in the air brought you a lucky day. They floated slowly in spirals, as we threw sticks for the conkers, which we warmed in the oven till they were as hard as stone, then fought each other bruising our knuckles.

—Derek Jarman, Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook

One of the most important artists and gay rights activists of his generation, Derek Jarman made groundbreaking avant-garde cinema, such as Sebastiane (1976), Jubilee (1978) and Caravaggio (1986), garnering praise for their audacious homoerotic content.

It would be Blue (1993)—part art installation, part requiem—that became his iconic masterwork. Drawing inspiration from the French performance artist, Yves Klein (1928–1962), whose concept of “the void”, a place where the individual could steep in the profound inner world of their subjective experience and imagination, was expressed via large-scale monochrome canvases painted in a pigment known as International Klein Blue (IKB) or Pantone 286C.

In similar vein, Jarman used IKB as the visual backdrop to his confessional film, over which he superimposed a biographical narrative and distinctive sound design, outlining his reflections on life and love as the AIDS virus continued to wreak havoc on his body. Specifically, the degeneration of his eyesight precipitated a permanent blue vision, prompting him to ask poignantly: “If I lose half my sight will my vision be halved?”

At first, people thought I was building a garden for magical purposes—a white witch out to get the nuclear power station. It did have magic—the magic of surprise, the treasure hunt. A garden is a treasure hunt, the plants the paperchase.

I invest my stones with the power of those at Avebury. I have read all the mystical books about ley-lines and circles—I built the circles with this behind my mind. The circles make the garden perfect—in winter they take over from the flowers. There was magic and hard work in finding the coloured stones for the front: white, difficult; grey, less so; red, very rare.

Some of the flints are over a foot high: these are the central hub; some are grey, a few very white and a warm brown, the others mottled white and grey. The bricks, washed smooth by the tide, bring a jolly flash of red.

—Derek Jarman, Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook

Approaching the front garden of Prospect Cottage, I notice that the red and orange poppies of my summer visit have vanished, making the simple geometric patterns of circles and squares all the more striking, which are marked out by flints and stones, offset by driftwood totems standing proud amidst clumps of gorse and tufts of sea kale.

To the left of my peripheral vision looms Dungeness Nuclear Power Station, now non-operational, its angular concrete structure standing soulless against the skyline. In perfect counterpoint, the lefthand exterior wall of the cottage is embossed with the impassioned words of John Donne’s poem, “The Sunne Rising”, in powerful testament to the preciousness of life and the shameless, secret pleasures of human relationships.

A small group of visitors are already waiting on the doorstep—two official curators and a couple from a neighbouring county—as the wind whips our hair and the bright afternoon sunlight temporarily blinds our view. Then, on the dot of 12:30 p.m., our names checked against the register, we all step silently inside.

Prospect Cottage, its timbers black with pitch, stands on the shingle at Dungeness. Built eighty years ago at the sea’s edge—one stormy night many years ago waves roared up to the front door threatening to swallow it … Now the sea has retreated leaving bands of shingle. You can see these clearly from the air; they fan out from the lighthouse at the tip of the Ness like contours on a map.

Prospect faces the rising sun across a road sparkling silver with sea mist. One small clump of dark green broom breaks through the flat ochre shingle. Beyond, at the sea’s edge, are silhouetted a jumble of huts and fishing boats, and a brick kutch, long abandoned, which has sunk like a pillbox at a crazy angle; in it, many years ago, the fishermen’s nets were boiled in amber preservative.

There are no walls or fences. My garden’s boundaries are the horizon. In this desolate landscape the silence is only broken by the wind, and gulls squabbling round the fishermen bringing in the afternoon catch.

—Derek Jarman, Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook

As we walk reverentially around the five rooms appendaged to a narrow, central corridor (sitting room, study, studio, bedroom and kitchen) with a conservatory adjunct at the back, it is difficult to describe the overwhelming impact of imbibing the atmosphere of Derek Jarman’s inner sanctum. Indeed, entering the sacred atmosphere of the south-facing lounge, decorated with holey stones and vivid abstracts, precipitates an unexpected rush of emotion as I find myself wiping away tears.

Similarly, the study opposite at the front of the cottage, panelled in boat wood with its shrine of knick-knacks paying homage to an unknown deity, is where one can truly appreciate the cottage’s magical prospect of the garden, shingle beach and overarching sky. Positioned right in front of the window, Jarman’s salvaged writing desk is where he would regularly compose poetry and gardening notes in his distinctive calligraphy, as dawn broke each morning over the distant shoreline.

Then we move deeper into the cottage. First, the studio, with its tubes of paint and pots of brushes, a portrait of Derek Jarman by Maggi Hambling (apparently painted from memory) matrixed in IKB and an impressive glass-cabinated bookcase showcasing Jarman’s exquisite taste in literature—the novels of Jack Kerouac, horticulture manuals, plays by William Shakespeare. Next, Jarman’s wooden-panelled bedroom, bare and monastic, adorned with a provocative picture of Christ hanging on the cross. And finally, the kitchen where the glowing red hips of a dog rose outside the galley window frame the view of the power station beyond.

I find it mysterious that all the years that have passed should lead to Prospect Cottage—perhaps it is the tin roof which reminds me of the Nissen huts of an RAF childhood in its forties, so thrifty and far distant; maybe it is the flower bed which runs in front of the house—it has the same limps of concrete from some long-demolished fortification as those in Abingdon and Kidlington; or the stoves which roar in the wind; or maybe the name Prospect.

Today there is solitude, a half-hour has elapsed without a car passing and the phone is silent, and though it’s cold I’m well wrapped up in my grey sweater and an old corduroy jacket—as worn as a moss-grown wall. I feel higgledy-piggledly. No appetite today.

A view of boats fuzzed by the dismal rain that patters on the metal roof. The smallest money spider is building a web on the desk light, so fine that my breath swings it back and forth. It’s possible to be alone here.

—Derek Jarman, Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook

As our guides point out the significance of an objet d’art here, a photograph there, I try to imagine what it would actually be like to live at Prospect Cottage and discover to my utter delight that Creative Folkestone offers residencies as well as special research and development opportunities for those wanting to experience intimately Jarman’s home, not as a static museum trapped in the bygone past but as a living attestation to the beauty of art and the creative process.

Our final destination is the conservatory at the northern end of the cottage, which is now drenched in afternoon sunshine, accessed by a connecting corridor, hung with gardening tools, paintings and yet more cabinated bookshelves. There is a visitors’ ledger on the coffee table, which I dutifully sign, trying to conjure up my feelings into a succinct single sentence of appreciation before we exit through the back door and the tour comes to a close.

The rear garden is less formal than the front being more wild and scattered, with rusted metal jags and stubborn mounts of broom and gorse. As there are no fences in Dungeness to mark out the perimeters of properties, Prospect Cottage blends naturally into the surrounding landscape, reaching out as far as the distant horizon.

A hallucinatory dusk, washed with colours to drive Monet to suicide. At sunset the brightest sickle moon appeared in a gentle blue sky; minute by minute tethering in intensity it stayed until just before midnight.

Night clear as a bell—the blue passed through violet with strands of rose and old gold to become a deep indigo. So etched were the moon and stars they seemed to have been cut out by a child to decorate a crib.

The night sky here is a riot that outshines the brightest lights of Piccadilly; the stars have the intensity of jewels. So flat is the Ness that those stars that lie at the horizon touch your very feet and the moon tips the waves with silver.

The nuclear power station is a great ocean liner moored in the firmament, ablaze with light: white, yellow, ruby. Whilst round the bay the lights stretch from Folkstone to Dover. High above, jet liners from the south flash silent in the stars. On these awesome nights, reduced to silence, I walk across the Ness.

Never in my many sleepless nights have I witnessed a spectacle like this …

—Derek Jarman, Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook

On previous visits, I have walked across the grinding waves of shingle, weaving through upturned boats and abandoned fishermen’s huts, finally reaching the seam of the sea, often in a state of exhaustion.

Today, I am happy simply to drive slowly along Dungeness Road, up towards the lighthouse and take in the view more effortlessly—birds swooping onto telegraph wires, laundry billowing on clothes lines, the Snack Shack selling the daily catch of fish.

Then the foreboding structure of the power station comes into view and yet despite its austere exterior, I suddenly feel strangely capitated by its ominous beauty. Accepting of all that is. At peace.

The rain and fine warm weather have quickened the landscape—brought the saturated spring flowers early. The dead of winter has passed. Today Dungeness glowed under a pewter sky—shimmering emeralds, arsenic, sap, sage and verdigris greens washed bright, moss in little islands set off against pink pebbles, glowing yellow banks of gorse, the deep russet of dead bracken, and pale ochre of reeds in clumps set against the willow spinney—a deep burgundy, with silvery catkins and fans of ochre yellow stamens fringed with the slightest hint of lime green of newly burst leaves.

This symphony of colour I have seen in no other landscape. Dungeness is a premonition of the far North, a landscape Southerners might think drear and monotonous, which sings like the birch woods in Sibelius’ music.

From my home I can see the sun clamber out of a misty sea. It wakes me through the bedroom window and then stays with me all day. There are no trees or hills to hide it. When it sets over the flatlands in the west I sit and watch it on a throne-like chair that I rescued from a rubbish dump. I never miss the setting sun, however cold the weather.

—Derek Jarman, Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook

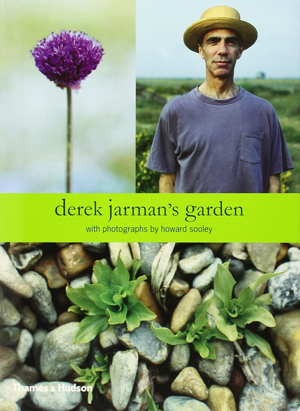

In 1989, the photographer, Howard Sooley, was commissioned to take pictures of Derek Jarman and Prospect Cottage, who was similarly captivated by his inspirational visits to Dungeness, his fondness for the garden and their profoundly enduring friendship.

Indeed, Sooley continued to visit Jarman until his death, joining him on trips scavenging for flotsam on the shingle beach and to local nurseries to buy plants, as well as driving him back and forth between St Bartholomew Hospital and Prospect Cottage when Jarman became increasingly frail and infirm.

Born out of their mutual respect for the other’s artistic practice, Jarman and Sooley subsequently collaborated on a book of photography and journal entries depicting their horticultural work together, which was published shortly after Jarman’s death—a fitting tribute to a remarkable garden and an even more remarkable gardener.

The gardener digs in another time, without past or future, beginning or end. A time that does not cleave the day with rush hours, lunch breaks, the last bus home. As you walk in the garden you pass into this time—the moment of entering can never be remembered. Around you the landscape lies transfigured. Here is the Amen beyond the prayer.

Dante, at the beginning of his journey back along the great antique sprial, entered this realm in a dark wood.

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

Mi ritrovai per una selva oscura

Ché la diritta via era smarritaIn the middle of our life’s journey

I found myself in a dark forest

Because the straight path was lost—Derek Jarman, Pharmacopoeia: A Dungeness Notebook

*

Images: Paula Marvelly, Prospect Cottage & Dungeness

(CC BY-SA 4.0) The Culturium

Post Notes

- Creative Folkestone: Prospect Cottage

- Howard Sooley: Photographs of Prospect Cottage

- Virginia Woolf: A Room of One’s Own

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Matsuo Bashō: The Narrow Road to the Deep North

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Henry David Thoreau: Walking

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Rollo May: My Quest for Beauty

- Alan Watts: Cloud-Hidden, Whereabouts Unknown

- Jack Kerouac: Alone on a Mountaintop

- Jean Cocteau: Chapelle Saint-Pierre de Villefranche-sur-Mer

- David Lynch: Catching the Big Fish