Image: Public Domain

Towards a more perfect future

“Real beauty knocks you a little bit off-kilter.”

—David Byrne

CAROL RAPHAEL is an American book editor, writer on the arts and photographer currently living in Portland, Oregon. Her writings have appeared in magazines such as EnlightenNext magazine (formerly known as What Is Enlightenment? magazine) and the German publication Evolve, as well as newspapers and various national and international arts periodicals. She has travelled widely and lived in France, Italy and the UK.

A regular contributor to The Culturium, in this month’s guest post Carol examines the nature of beauty, specifically the pulchritudinous aesthetic of the visual arts. By taking inspiration from a wealth of illustrious examples, she argues for a return to the harmonious compositional elements that elevate the soul ever upwards, so wanting in our postmodernist age.

Beauty is a topic of endless fascination and one that is constantly in flux as cultures transform. What constitutes beauty is never fully resolved. Treatises from humanity’s finest thinkers have been devoted to nailing down beauty’s elusive qualities for centuries. Whether it’s embellishing the human body or decorating our surroundings, the allure of beauty has occupied the human imagination since the beginning of recorded history, if not before.

Pleasing the eye and observing that which pleases the eye are the provenance of beauty. The visual arts—painting, drawing, sculpture, architecture—in particular, originated in the desire to bring meaning, uplift, and grace to life. It is the beauty we create, rather than the beauty we find in nature or a pretty face that I want to address. Specifically, I’d like to look at beauty in the context of our contemporary, postmodern world.

Up until recently, art and beauty were linked. To make a work of art meant to make a beautiful object or image, even if the subject matter was less than gracious—say, a battle scene or a mythological rape. Take Greek art, for example. Combat scenes and warriors were common themes on vase paintings from the earliest periods of Greek art, and the story of Leda and the swan, in which the god Zeus takes the form of a swan to seduce Leda, is not uncommon in ancient Greek art. Though depicting acts of violence, the subject matter was portrayed with elegance, proportion, fine drawing, and emotional restraint.

One of the great paintings of early Renaissance art is a battle scene: the Battle of San Romano by Paolo Uccello. Images of lances, spears, armour, fallen horses, and wounded soldiers are used to transform the confusion and chaos of the event into a scene of harmonious forms, complex patterns of richly coloured shapes, and ornate and luscious detailing, all with a remarkable mastery of the newly discovered technique of linear perspective. Yes, honouring Florence’s victory over its arch-rival Siena was the purpose of the painting, but in Uccello’s hands, the reality of warfare is elevated to a meditation on the underlying structure of the physical world.

Image: Public Domain

Beauty as an essential characteristic of painting or sculpture was rejected in the early part of the twentieth century, and for good reason. A group of artists in Europe and the United States known as the Dadaists reacted to the atrocities that were occurring as World War I broke out. In the midst of slaughter and destruction, the only sane response for artists, they posited, was to refuse to make art of beauty and meaning. The world had gone crazy, and art should reflect that madness by being itself nonsensical and without beauty.

In a sense, the Dadaists opened a Pandora’s box of art taboos. As the century unfolded, more and more expectations about what constituted a work of art were discarded. At the same time, the market for art expanded exponentially, making the purchase of a work of art for many people as much an act of financial investment as it was an affirmative aesthetic response on the part of an art connoisseur. What came to be valued most in art was, as art critic Robert Hughes pointed out, the shock of the new. Add to that the escalating price tag associated with that shock value, and a situation developed that today we take for granted: auction sales in the millions of dollars for a piece such as a gleaming stylized puppy sculpture or a dishevelled postcoital bed or an obese woman splayed on a shabby couch. In short, objects and images that flaunt their disdain for beauty, serious content, or universal truth sell.

Under such circumstances, the return of beauty in art would not only be a balm to the eye but a significant way to imbue art with meaning and purpose again. Here’s why.

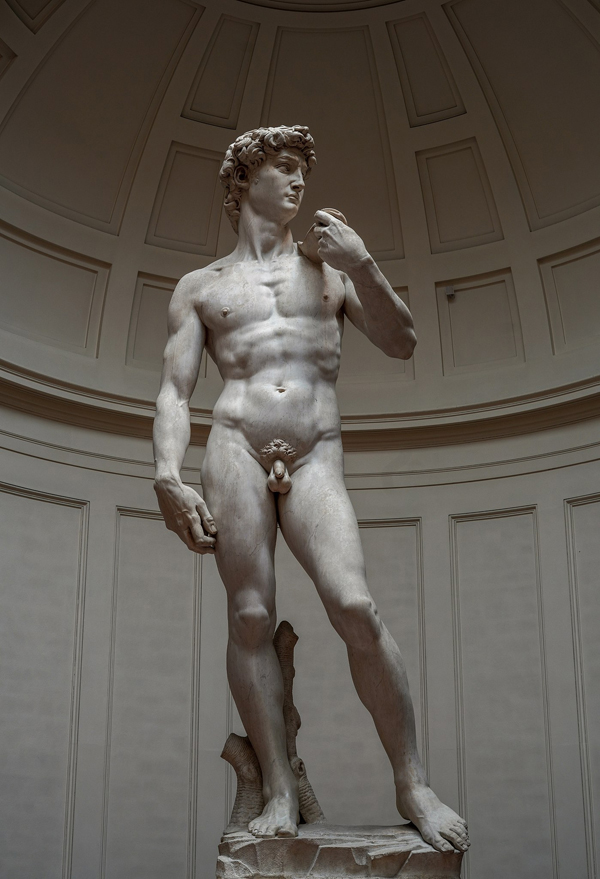

First, beauty takes your breath away, at least momentarily. You come to rest, are silenced, in awe. While working as a tour guide in Florence, Italy, I took nearly all my clients to see Michelangelo’s noble, larger-than-life marble sculpture David. And every time I turned the corner in the Accademia Gallery and saw the heroic youth standing at the end of the hall, I would stop in my tracks. Not once was I unmoved by the extraordinary beauty of Michelangelo’s masterpiece.

Image: Public Domain

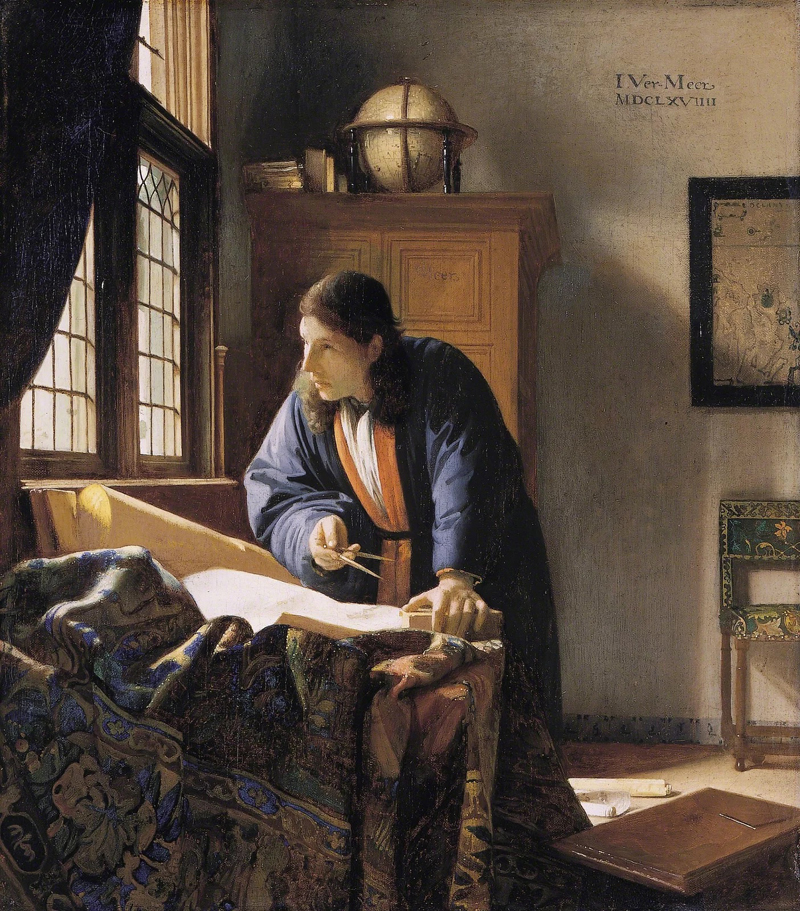

In those moments of stillness, when confronting beauty, many things can happen. Perhaps most important, we forget ourselves. Absorbed by the luminosity of a painting by the seventeenth-century Dutch painter Jan Vermeer or lost in the intricacies of a sensuous line in an etching by Rembrandt van Rijn, we forget where we are and who we are. Simone Weil referred to this loss of self-centeredness as ‘de-centering’. Our attention is not occupied with how we appear to others—the narcissist’s self-concern—but with what appears before our eyes. We see a vision of perfection. We see a glimpse of the divine. For the divine is godly perfection.

Image: Public Domain

Harvard professor Elaine Scarry, in her book On Beauty and Being Just, makes the case that this temporary dropping of self-preoccupation that beauty can elicit also promotes justice. When beauty opens our hearts, she proposes, our capacity to care for what is just and true expands. Indeed, the triumvirate of values—truth, beauty, and goodness—has long served as a cornerstone of Western philosophical thought and deserves deeper consideration than this brief essay allows.

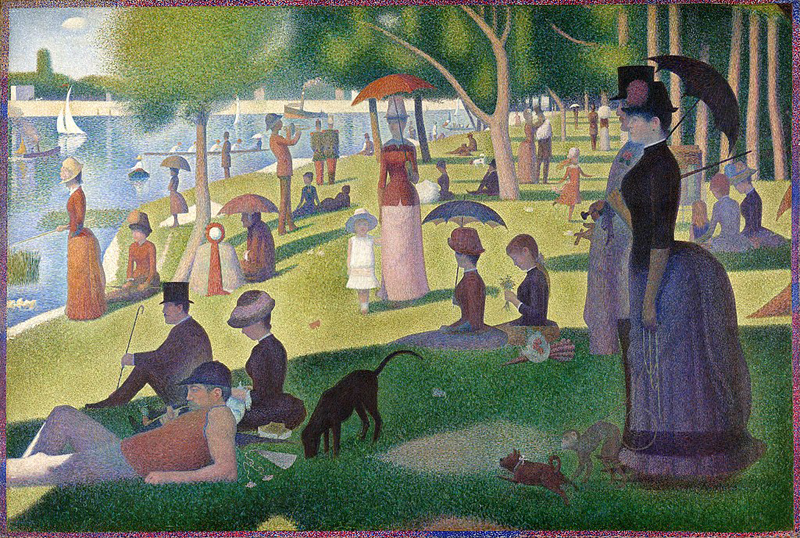

Image: Public Domain

Beauty also sharpens our awareness. Awakened by the beauty we observe in a great work of art, such as Georges Seurat’s stately pointillist tableau A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, our vision becomes enlivened and our perception is heightened. That vision, I’d like to suggest, has as much to do with observing art and the outer world that surrounds us as it does with knowing the inner landscape of our dreams, meditations, and aspirations. The outer stimulus feeds an inner response and vice versa. What we see takes us deep within ourselves, and awakening to the most intimate sense of who we are impels us to respond to the external world. Often when we see a beautiful image we are inspired to create beauty ourselves, whether we are artists or not. We long for more beauty in the world, and we strive for the splendour that we want to behold. Beauty is the ultimate attractor. It pulls us out of ourselves and tempts us with the possibility of ever more beauty and more perfection. It arouses us to do better.

The Jesuit priest, scientist, and visionary Pierre Teilhard de Chardin said, ‘More primordial than any idea, beauty will be manifest as the herald and generator of ideas.’ He understood the power of art to express spiritual energy, which he believed was first produced on earth symbolically in art. It is this spiritual and evolutionary function of beauty—the power to generate life-affirming change—that is so vital to the visual arts and culture in general, and it is what is intentionally absent in much postmodern art.

Certainly, the horrors of warfare that the Dadaists were protesting are still with us today and show little sign of abating. If anything, our tolerance for conflict and suffering seems to be increasing. But eschewing beauty does not have the impact it did a century ago. Indeed, our acceptance of the inelegant, the lewd, and the ugly may have inured us to pain rather awakened us to its horror.

I’d like to suggest that restoring the centrality of beauty in art may offer a small way to change course. In addition to offering respite from so much that is tawdry in our world, it would be an opportunity to value beauty not for its own sake, but for its capacity to inspire more positivity, harmony, and shared humanity. It just may be that an appreciation of beauty can help lead us to a more perfect tomorrow.

[This article first appeared with minor modifications in the

March–May 2009 edition of EnlightenNext magazine.]

Post Notes

- Victor Kossakovsky: Gunda + Marie Amiguet & Vincent Munier: The Velvet Queen

- Scott Guyon: Why Beauty Matters

- Paolo Sorrentino: The Great Beauty

- Rupert Spira: A Meditation on I Am

- Paul Cézanne: La Montagne Sainte-Victoire

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Jean Cocteau: Chapelle Saint-Pierre de Villefranche-sur-Mer

- Henri Matisse: Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- Mark Rothko: The Artist’s Reality

- Bill Viola & Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth