Carlos Reygadas, Japón

The sacrifice

Before going on to the particular problems of the nature of cinematic art, I feel it is important to define my understanding of the ultimate aim of art as such. Why does art exist? Who needs it? Indeed, does anybody need it? These are questions asked not only by the poet but also by anyone who appreciates art … [T]he goal of all art … is to explain to the artist himself and to those around him what man lives for, what is the meaning of his existence. To explain to people the reason for their appearance on this planet; or if not to explain, at least to pose the question …

In a very real sense every individual experiences this process for himself as he comes to know life, himself, his aims. Of course, each person uses the sum of knowledge accumulated by humanity but all the same, the experience of ethical, moral self-knowledge is the only aim in life for each person and, subjectively, it is experienced each time as something new.

Again and again, man correlates himself with the world, racked with longing to acquire, and become one with, the ideal which lies outside himself, which he apprehends as some kind of intuitively sensed first principle. The unattainability of that becoming one, the inadequacy of his own ‘I’, is the perpetual source of man’s dissatisfaction and pain. And so art, like science, is a means of assimilating the world, an instrument for knowing it in the course of man’s journey towards what is called ‘absolute truth’ …

Art is born and takes hold wherever there is a timeless and insatiable longing for the spiritual, for the ideal: that longing which draws people to art … in artistic creation the personality does not assert itself, it serves another, higher and communal idea. The artist is always a servant and is perpetually trying to pay for the gift that has been given to him as if by a miracle.

—Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema

IT TOOK ME several days to recover from watching Japón by Carlos Reygadas (born October 1971). A mesmerizing meditation upon the human condition—specifically the nature of death, both literally and existentially—, its essence seeped so very deeply into my soul, I was left feeling simultaneously devastated as well as utterly transformed. Inspired by the visionary films of Andrei Tarkovsky, the Mexican auteur’s outstanding debut feature is a testament to the fragility of life counterpointed by the power of love and devotional faith.

Unlike the psychological realism of present-day motion pictures, Carlos Reygadas joins an elite league of directors who champion a transcendental style of filmmaking or “slow cinema”, which is hallmarked by its focus on nominal plot and dialogue, panoramic landscapes and diegetic acoustics, coupled with an emphasis on paying attention to the here and now in a quest for absolute truth and the meaning of our very existence. Indeed, founding forefathers, Yasujiro Ozu, Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer and Andrei Tarkovsky, paved the way for Carlos Reygadas and his contemporaries, namely Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Béla Tarr, Theo Angelopoulos, Ben Rivers, Abbas Kiarostami and Apichatpong Weerasethakul, to name but a few, offering us a minimal and ethereal aesthetic, elevating their craft into the realm of sacred art.

Photograph: © Mantarraya Producciones

Cinema is primarily about capturing existence. It’s the part that I appreciate most about the medium. The camera records things that are actually happening, even if it has been staged, which is often the case in commercial cinema. Recording life is the essential aspect for me. I make films to acknowledge that I’m alive. I want to know who I am and why we’re here. What can you think about if not ordinary life and all the mysteries that flow from it? All my thoughts and feelings are connected to experiences in my daily life. Life is experiencing through our senses. When you see, smell, touch and feel, you communicate with other people and with the things around us. Sensuality is the main tool.

—Carlos Reygadas

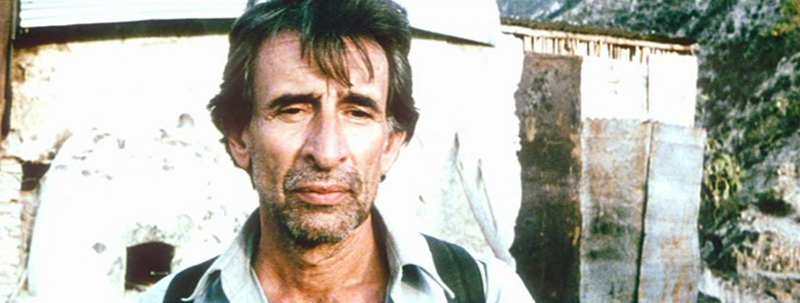

On the face of it, the plot of Japón is fairly straightforward: an unnamed man (played by Alejandro Ferretis) in the midst of an existential crisis leaves Mexico City and heads to the remote countryside village of Ayacatzintla in the state of Hidalgo, where he intends to end his life. The opening sequence—moving from a darkened motorway underpass replete with glowing tailgates into the daylight of the city, flanked by tenement buildings and billboards, then yielding to dirt roads and lush vegetation—is heightened with one of the film’s few orchestral accompaniments, taken from the final movement of Shostakovich’s 15th Symphony. As we transition from urban to rural life, the mood is set—grandiose, intense, singular—and our journey unfolds from the familiar into the unknown.

Taking lodgings with an old Indian woman (played by Magdalena Flores) named Ascen (short for Ascención) in her ramshackle abode on an escarpment of a desolate canyon, The Man, who is a painter, is plagued with suicidal thoughts and yet he is reticent about following them through to any kind of permanent conclusion. As the days and weeks pass in the vastness of the natural landscape, he is viscerally reinvigorated by his landlady’s humble and tender humanity, as well as his newly found rustic existence; slowly but surely his will to live returns, reawakening within him formerly dulled senses and repressed desire.

Photograph: © Mantarraya Producciones

My goal is to observe life and not to mystify it. What I film is simply matter that exists in the world. A person or object may have a particular meaning within the context of the film but I don’t see them as having an inherent conceptual identity. If I say the word ‘tree’, you don’t necessarily need to see the tree because you have learned since you were a child how to conceptualize the tree. In most narrative films, things—whether it’s a bird, a human body, a cloud, a car or a sound—exist as devices that only serve to tell a story. This is true for the actors as well. These types of films do not allow the viewer to see the actors as people existing in the world. Instead, the viewer sees a mask moving around in a costume and wearing lots of make-up. My goal is to bring out the individuality of each person or object and to capture something of their essence. I’m not interested in filming the mask. This is why you see the particular bodies in the films. If they are not ‘conventional’ —if they are considered old, ugly or fat—I couldn’t care less; they are all people and they are all equally beautiful. Filming people as they are is my way of showing them respect.

—Carlos Reygadas

Stunningly shot in 16mm panoramic cinemascope, Japón is the epitome of transcendental artistry—cicadas pulse in the grass, wind susurrates through the leaves, rain thrums on the roof. And yet the beauty of the arid landscape is in stark contrast to the tumbledown dwellings and bestial cruelty, which keep the film from descending into sentimentality and pretty pastiche. In an early scene, walking through agave fields with the aid of a cane, The Man meets a young boy hunting fowl, who presents him with an injured bird, barely alive, being incapable of snapping its neck himself. “My fingers are not strong enough,” he says, handing the bird to The Man, who promptly rips off its head and casts it onto the ground. We then see the head in close-up, instinctively blinking and gasping for life.

I actually retched upon my very first viewing but have subsequently found great beauty in this particular shot—the composition, the textures, the way in which the colour of the feathers blend into the mottled terrain. One could say that the decapitated bird is a metaphor for The Man himself: disembodied and broken, struggling to breathe. It is his silent sojourn into the serenity and stillness of the Mexican scenery that will finally liberate him and set him free.

Photograph: © Mantarraya Producciones

Typically, we have either an omniscient or a first-person narrator. But there’s probably another more fluid mode and this is the way I work. It’s closely related to the way I dream, it’s a space where nothing is very clear. We don’t always know who’s speaking or where things come from but there is a flow that connects everything. During the process of writing a film, I experience a similar perception. I spend a long time thinking about a film before putting a letter on paper; once started, I’m able to write the entire screenplay in two or three days. You can compare this with a trance-like state that allows visions to emerge. Even to me, it is not entirely evident how this happens.

—Carlos Reygadas

Reflecting upon the director’s words reminds me of American writer, Carlos Castenada, whose mystical visions formed the very basis of his writings, in which he expounded his apprenticeship with a self-proclaimed Yaqui Indian Sorcerer, don Juan Matus from Sonora, Mexico. Indeed, both Reygadas and Castenada are seemingly able to access the realm of the Wholly Other, bringing back its esoteric secrets and presenting them with a unique and deeply personal proclamation of what it is like to experience, and be at one with, the flow of life.

Moreover, speaking in an extended interview in the special features section on the DVD, Carlos Reygadas says his films, specifically Japón, explore the way which his characters are motivated by their unconscious impulses, not even known to their conscious minds. In his striving for purity of intent and authenticity of purpose, with the exception of Alejandro Ferretis who plays The Man, all of Carlos Reygadas’ dramatis personae, in true Bessonian style, are portrayed by non-professional actors. It is difficult to imagine how it could have been any other way.

Photograph: © Mantarraya Producciones

Everything we do has both a physical and a spiritual dimension. The two exist simultaneously. This is true for sex. For me, personally, there’s no more spiritual way of expressing love than through a sexual act. Love is caring for and desiring another person and it can be expressed in different ways. It can be through conversation and talking about what you feel and what you see. It can be caressing and kissing them, and it can be about going as far as you can with someone physically, as sexual intercourse. These are all expressions of love, they can happen with your lover or with a stranger you’ve just met. It’s about two people sharing a bond and it doesn’t matter who they are or what sex they belong to. It’s just about experiencing together the most powerful physical connection possible. In Japón, the man begins to feel alive again while he is staying with Ascen. It’s not that he wants to have sex with her because he loves her. It’s that together they create a bond. Sex occurs to them because they feel a powerful attraction and they just let go.

—Carlos Reygadas

As the film progresses, we witness an intimate connection develop between the principal protagonists by way of fleeting and touching moments spent together—conversing about art, smoking marijuana, drinking ice tea—so much so that their sexual intercourse is a natural expression of their bond. Scenes of physical intimacy can be unsettling to watch (and no doubt to act) and yet their union is deeply moving, despite the fact that it is ostensibly awkward and mechanical, as well as subverting stereotypical notions of how sex between two people should be portrayed. The Man’s coital release evokes a surge of emotion whereupon he breaks down and weeps, only to be comforted by Ascen’s healing hands; her body may be frail and withered and yet it is she who manifests psychological and spiritual strength.

The poignancy of their lovemaking is brought into further relief by its juxtaposition to the previous scene set inside a church during the Eucharist when the sacramental bread and wine are transubstantiated into the body of Christ. And so it is with our protagonists: their offering unto one another consecrates their corporeal exchange giving new life to The Man by way of Ascen’s self-sacrifice, both sexually to him and then later, indirectly, in her submission of property rights to her nephew.

Photograph: © Mantarraya Producciones

[I]f I could talk about these things, I would probably be a writer instead of a filmmaker. It is my intuition that sharpens my searching and feeling. Making a film is about wanting to acknowledge that I am alive and to communicate with other people. It’s not necessarily about transmitting ideas. It’s more about relating to others on a more basic level. This is the core and the goal. Reality is never simply a collection of facts. It’s composed of our thoughts, memories, dreams and projections of the future. These are ineffable things that the cinema strives to depict.

—Carlos Reygadas

The closing scenes of Japón are utterly heartwrenching. In a final artistic homage to Andrei Tarkovsky and the iconic sequence in Stalker, in which the main protagonists take a journey along a disused railway line, the dénouement of Carlos Reygadas’ masterpiece is an emotional revelation, made all the more poignant by the ethereal score of Arvo Pärt’s Cantus. The camera sarabands between landscape and sky and sleepers as we are held spellbound in our yearning to understand what has happened to Ascen. When the lens finally comes to a standstill, we are forced to behold her inevitable fate.

Furthermore, as we ourselves project the unfinished story into the future, Ascen’s oblation breathes eternal life through our anonymous protagonist, whose own reality has been rejuvenated, regenerated, reborn. Despite not being lovers in the conventional sense and their lives taking dramatically different directions, it is the very act of loving itself that ennobles their spirits and dignifies their hearts. Indeed, Carlos Reygadas’ Japón is a visual tour de force, embodying the Tarkovskian metaphysical vision of elevating the mundane to the miraculous through the ascensional power of beauty manifested through the creative exposition of art.

Photograph: © Mantarraya Producciones

I see it as my duty to stimulate reflection on what is essentially human and eternal in each individual soul, and which all too often a person will pass by, even though his fate lies in his hands …

In the end everything can be reduced to the one simple element, which is all a person can count upon in his existence: the capacity to love. That element can grow within the soul to become the supreme factor, which determines the meaning of a person’s life. My function is to make whoever sees my films aware of his need to love and to give his love, and aware that beauty is summoning him.

—Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema

Post Notes

- Mantarraya Producciones

- Interview with Carlos Reygadas, Extra Extra Magazine

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinematic Genius

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Instant Light

- Leo Tolstoy: A Confession

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Sergei Parajanov: The Colour of Pomegranates

- Ben Rivers: Two Years at Sea

- Michelangelo Frammartino: Le Quattro Volte

- Liam Ó Muirthile: Camino de Santiago, Dánta, Poems, Poemas

- Teresa of Ávila: The Ecstasy of Love

- Marie Menken: Arabesque for Kenneth Anger

- Lisandro Alonso: Jauja

Join Our Newsletter