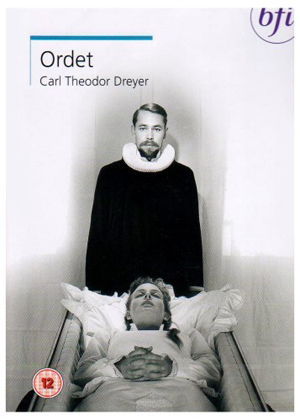

Carl Theodor Dreyer, Ordet

In the beginning was the word

Morten Borgen: And the rest of us, all the rest of us, we go straight down to hell to eternal torments, don’t we? Yes, that’s what you think, isn’t it?

Peter Petersen: Yes. Words, words, you have them all right.

—Carl Theodor Dreyer, “Ordet”

THE OPENING SHOTS of Carl Theodor Dreyer’s masterpiece, Ordet (The Word) must be some of the most iconic in cinematic history—set against a backdrop of swaying wheat and billowing laundry, a religious fanatic believing he is Christ the Saviour proclaims that only those who have faith shall enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

Adapted from the play by Kaj Munk, a Danish Lutheran priest, Ordet depicts a family torn apart by belief and religious ideology. Centred around the Borgen kin in the autumn of 1925, a devout widower and prominent member of the community, Morten (played by Henrik Malberg), has three sons: Mikkel (Emil Hass Christensen), the eldest, is agnostic and happily married to the pious Inger (Birgitte Federspiel), who is expecting their third child; Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye), who had a nervous breakdown whilst studying the philosophical works of Søren Kierkegaard, believes himself to be Jesus of Nazareth; and Anders (Cay Kristiansen), the youngest son, is lovesick for Anne (Gerda Nielsen), daughter of Peter Petersen (Ejner Federspiel), the leader of a local Inner Mission sect.

Photograph: © A/S Palladium

Actors can, according to my experience, be divided into two categories: those who build up their parts from the outside and those who build them up from within. The first ones shape the role almost like the sculptor who covers a wooden skeleton with clay until it has a human figure. He attaches great importance to details of makeup and costume and equips the figure with different ‘characteristic’ small features and gestures, e.g., a slightly stooping posture, a peculiar movement of the hands, a certain stroke with the glasses, a particular way of walking, a strange diction. Everything is deliberate, carefully considered and weighed, studied. When he has modelled in the clay long enough, the character stands as if ‘alive’ and the skilful actor of this category makes sure that the many details are assembled into a whole. But the role’s ‘ego’ never becomes identical with the actor’s ‘ego’. Even the most dramatic moments, the personal ‘ego’ stays outside, coolly contemplating, ready to correct if the physical ‘ego’ falls out of the role. This actor is thinking his role. He is acting.

The actor of the other category begins by identifying himself with the character he is to portray and he won’t be satisfied until his heart is beating in the other chest. He feels the part, he is the other person and, therefore, he cannot avoid convincing us. All that is essential to the actor of the first category becomes of secondary importance to this one. He can act with his own bare face and we will believe him because facial expressions, features, posture, walk and gestures are determined from within.

—Carl Theodor Dreyer, Dreyer in Double Reflection

Despite Danish filmmaker, Carl Theodor Dreyer (3rd February 1889–20th March 1968), making some of the most profound observations on the nature of the filmmaking process, not least the craft of acting itself, when viewed through twenty-first-century eyes, Ordet (1955) at first appears, somewhat paradoxically, to be staid, stilled and overly stage-managed in its delivery. And yet, we must remember that we are witnessing the art of a master director, one who intuitively understood the human condition, so when Inger suffers complications with her pregnancy, leading to her untimely death and her husband’s inconsolable grieving, the contrast of emotional states between the beginning and end of the film is such that we cannot help but weep along with him. Indeed, we are in no doubt that Mikkel Borgen is experiencing sensations of the most devastating kind, his world now ripped utterly asunder, and all flawlessly delivered by an actor delving deep within himself to make us, as audience, empathize with what he is feeling to be absolutely real.

Dreyer was no stranger to portraying the inner psychological states of his characters, the ebb and flow of emotion, the poetry of the human face. His tour de force, La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (The Passion of Joan of Arc) (1928) starring Renée Jeanne Falconetti as the eponymous heroine, is regarded as a landmark in the history of cinema, not least in its attention to close-ups, lighting and short-cuts. But whereas La Passion belongs to the world of silent pictures and is rooted in tragic historical drama, Ordet uses fictional storytelling within a domestic setting to convey existential themes and the possibility of spiritual transcendence through the use of sumptuous cinematography, ambient sound and the power of the human voice. (Interestingly, like her character, Federspiel was actually pregnant during the film’s production and Dreyer tape-recorded her labour pains while she was giving birth, later using the recording as a sound effect in the finished film.)

Photograph: © A/S Palladium

And now we come to the real question, namely: Where does the possibility of an artistic renewal of film lie? I, for my part, can see only one way: abstraction—but, in order not to be misunderstood, I hurry to define the word ‘abstraction’ as an expression for the perception of art which demands that an artist shall abstract from reality in order to reinforce its spiritual content, whether this is of psychological or purely aesthetic nature. Or said even more succinctly: Art shall represent the inner and not the outer life. Therefore, we must get away from naturalism and find alternatives in order to introduce abstraction in our pictures. The ability to abstract is the prerequisite. Abstraction gives the director a possibility to reach outside the fence behind which naturalism has enclosed the film. Cinema must work itself away from being a purely imitative art. The ambitious director must seek a higher reality than the one he obtains just by putting his camera up and copying reality. His pictures have to be not only visual but also spiritual experience. What is important is that the director share his own artistic and spiritual experiences with the audience, and abstraction gives him this possibility by allowing the director to replace objective reality with his own subjective perceptions …

This is the task of any creative artist: To let himself be inspired by reality and after that withdraw from it in order to give the work the form that the inspiration suggested to him. Therefore, the director must have the liberty to transform reality so that it will correspond to the inspired, simplified scene he has standing in his consciousness, for it is not the director’s aesthetic sense that should yield to reality—no, the opposite: reality should obey his aesthetic sense. For art is not imitation but subjective selection and so the director will include only what is necessary for a clear and spontaneous overall effect.

—Carl Theodor Dreyer, Dreyer in Double Reflection

Reading Dreyer’s elegant expositions on the raison d’être of his artistry gives an acute insight into his metaphysical vision, whereby the ontological realms of the outer and inner existence are naturally able to co-exist. In a truly brilliant scene shortly before Inger’s death in childbirth, the beams of the headlights of the doctor’s car are thrown through the window against the living room wall, casting abstract shadows and foretelling her imminent passing from this world, exemplifying Dreyer’s aesthetic sensibility to ethereal effect.

Mirroring the same geometrical play of light from the net curtains behind her, the final scene depicting Inger in her coffin similarly establishes the film’s supernatural quality and, through the prophetic words of Johannes Borgen, reveals to both the other characters and audience alike the possibility of a renewed and resurrected life through the grace and word of God. Indeed, the contrast between brightness and dark, the howl of the wind and the relentless ticking of the grandfather clock subtly alert us to the mystical dimension from the very outset, thus making the film’s shocking dénouement both miraculous and the most inevitable conclusion of all.

Photograph: © A/S Palladium

… the shooting script itself ought to be worked out by the film director—and by nobody else. It is definitely the film director’s job—and his alone. The screenplay can and should be made by the author and the director in collaboration but the director alone should have responsibility for the (shooting) script. It is he who is intermediary between script and screen. He has to visualize the writer’s thoughts. It is he who has to ‘see’ the images, not only ‘see’ the individual images but ‘see’ them in their changes and succession. It is he who creates the rhythm of the film through the selection and linking together of the motifs. The composition of the script is, therefore, the director’s rightful work, in the very truest sense of the word and if he doesn’t resist with his hands and feet other people who meddle in it, he lacks understanding of what the real task of direction consists in.

To let others work out a script for a director would correspond to giving a fully worked out drawing to a painter and asking him to put the colours on. Just as, for the artist’s eye, lines and colours constitute an indivisible whole, so too, for the film director, composing the picture and directing are inseparably connected. Therefore, a shooting script is not ‘technical’ but, in the highest degree, an ‘artistic’ matter. Through the script the director proves if he is an artist or not. From which it again follows that the director’s collaboration in the preparation of the manuscript is not only desirable but absolutely necessary. For only he, in his thoughts, is capable of carrying the lines of the manuscript further into the shooting script because he is the only one in whose mind the many elements a film consists of are fused into a unity.

—Carl Theodor Dreyer, Dreyer in Double Reflection

Dreyer is often affiliated with a group of auteurs—founding forefathers Yasujiro Ozu, Robert Bresson and Andrei Tarkovsky; and then later, Nuri Bilge Ceylan, Béla Tarr, Theo Angelopoulos, Ben Rivers, Abbas Kiarostami and Carlos Reygadas—who are proponents of a transcendental style of filmmaking or “slow cinema” whereby the sacred realm of human existence is an integral element of the drama. Indeed, without doubt, Ordet is on a parallel with Tarkovsky’s Stalker, one of the greatest films ever to be made in terms of its homage to all that is divine and other-worldly.

Moreover, reiterating Dreyer’s words that it is the director’s sole responsibility not only to create a feeling of unity within the artistic and spiritual vision of the movie itself but also to ensure the entire physical experience be a unified whole, it is little wonder, therefore, that the resulting combination garnered Ordet the Golden Lion at the 16th Venice International Film Festival in 1955.

Photograph: © A/S Palladium

There is a certain resemblance between a work of art and a person. Just as one can talk about a person’s soul, one can also talk about the work of art’s soul, its personality. The soul is shown through the style, which is the artist’s way of giving expression to his perception of the material. The style is important in attaching inspiration to artistic form. Through the style, the artist moulds the many details that make it whole. Through style, he gets others to see the material through his eyes. Style is not something that can be separated from the finished work of art. It saturates and penetrates it, and yet is invisible and indemonstrable. All art is a single person’s work. But a film is created by a collectivity and a collectivity cannot create art unless an artistic personality stands behind it and acts as a driving force.

The first creating impulse for a film comes from the writer whose work is the actual foundation for the film. But from the moment the poetic foundation is laid, it is the director’s task to give the film its style. The many artistic details are born through this initiative. It ought to be his feelings and moods that colour the film and that awaken corresponding feelings and moods in the spectator’s mind. Through the style, he infuses the work with a soul—and that is what makes it art. It is for him to give the film a face—namely his own. Because it is like this, we directors have a very large responsibility. We have it in our hands to lift the film from industry to art, and, therefore, we must go to work with seriousness, we must want something, we must dare something, and we must not jump over where the fence is lowest. If film as an art is not to come to a standstill, we must work to create a mark of style, a mark of personality in the film. Only from this can we expect renewal.

—Carl Theodor Dreyer, Dreyer in Double Reflection

In the hands of a lesser director, the filming of Ordet would have, most probably, drowned under the weight of its oppressive religiosity and theological rhetoric about Christianity and the nature of faith; with Dreyer infusing his unique style—nay, his very soul—upon the narrative, however, he reveals unto us a world where God is incarnate in ordinary, everyday existence.

Moreover, by making Inger the central focus of the film and thereby choosing to alter the ending of Kaj Munk’s play to suit his subjective selection, Dreyer demonstrates how love and wisdom triumph over intellect and reason, how suffering can be transfigured into beauty and how there is a still and silent place where words are no longer needed and death may be transmuted into life.

Photograph: © A/S Palladium

Style in an artistic film is the resultant of many different components such as the play of rhythms and lines, the mutual tension of colour surfaces, the interaction of light and shadow, the camera’s gliding rhythms—all of which, together with the director’s interpretation of the material as an image-generating factor, is decisive for his artistic form of expression—his style! If he confines himself to a soulless, impersonal copy of what his eyes are seeing, he has no style. But if he, in his mind, takes what he sees and works it into a vision and if he builds up the images of the film in accordance with this vision, regardless of the reality that inspired him, then his work will bear the holy stamp of inspiration—then the film will have style, for style is the imprint of personality in the work.

—Carl Theodor Dreyer, Dreyer in Double Reflection

Post Notes

- Pavel Lungin: The Island

- Satyajit Ray: Charulata

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Paula Marvelly: The Monasteries of Meteora

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinematic Genius

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Instant Light

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Ben Rivers: Two Years at Sea

- Terrence Malick: The Tree of Life

- Carlos Reygadas: Japón

- Lisandro Alonso: Jauja