W. W. Norton, The Making of The Red Book

How an existential crisis precipitated an artistic masterpiece

[I:] I feel that I must speak to you. Why do you not let me sleep, as I am tired? I feel that the disturbance comes from you. What induces you to keep me awake?

[Soul:] Now is no time to sleep, but you should be awake and prepare important matters in nocturnal work. The great work begins.

[I:] What great work?

[Soul:] The work that should now be undertaken. It is a great and difficult work. There is no time to sleep, if you find no time during the day to remain in the work.

[I:] But I had no idea that something of this kind was taking place.

[Soul:] But you could have told by the fact that I have been disturbing your sleep for a long time: You have been too unconscious for a long time. Now you must go to a higher level of consciousness.

[I:] I am ready: What is it? Speak.

[Soul:] You should listen: To no longer be a Christian is easy. But what next? For more is yet to come. Everything is waiting for you. And you? You remain silent and have nothing to say: But you should speak. Why have you received the revelation? You should not hide it. You concern yourself with the form? Is the form important, when it is a matter of revelation?

[I:] But you are not thinking that I should publish what I have written? That would be a misfortune. And who would understand it?

[Soul:] No, listen! You should not break up a marriage, namely the marriage with me, no person should supplant me … I want to rule alone.

[I:] So you want to rule? From whence do you take the right for such a presumption?

[Soul:] This right comes to me because I serve you and your calling. I could just as well say, you came first, but above all your calling comes first.

[I:] But what is my calling?

[Soul:] The new religion and its proclamation.

[I:] Oh God, how should I do this?

[Soul:] Do not be of such little faith. No one knows it as you do. There is no one who could say it as well as you could.

[I:] But who knows, if you are not lying?

[Soul:] Ask yourself if I am lying. I speak the truth.

—Black Book 7, C. G. Jung, quoted in The Red Book, Liber Novus

Image: © Philemon Foundation

and W. W. Norton & Company

IN A WORLD awash with psychological, philosophical and metaphysical theories on just about every single aspect of cognitive experience, it is a revelation and a wonder to discover a literary and artistic masterpiece, unknown to the public eye until only a few years ago, composed by probably the greatest exponent of the human condition ever to have lived.

Akin to T. S. Eliot composing his seminal poem, The Waste Land, in the wake of a nervous breakdown, Carl Gustav Jung was similarly experiencing his own interior crisis, precipitated by the acrimonious split from his mentor, Sigmund Freud, as well as a series of apocalyptic precognitive visions heralding the outbreak of the First World War.

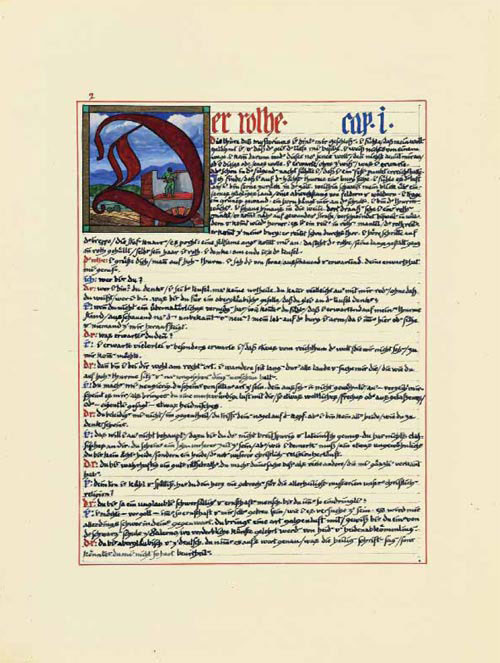

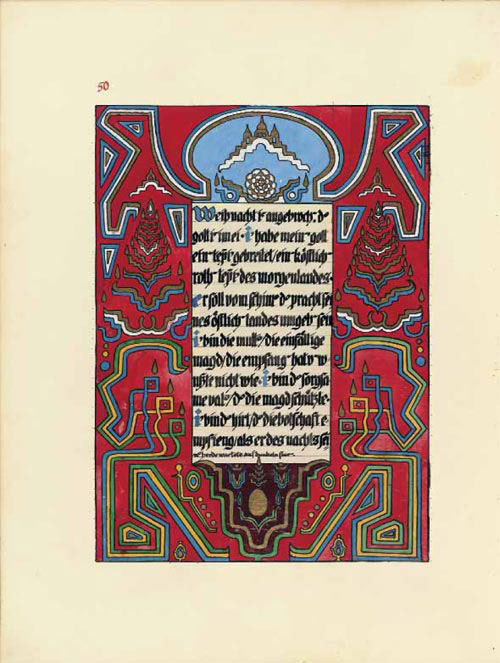

Out of this emotional maelstrom and yet not published in full until 2009, Jung’s The Red Book, also known as Liber Novus (New Book), is a breathtaking calligraphic and illuminated pilgrimage of self-analysis and inner transformation, resulting in his sublimest ever work.

Image: © Philemon Foundation

and W. W. Norton & Company

When I had the vision of the flood in October of the year 1913, it happened at a time that was significant for me as a man. At that time, in my fortieth year of my life, I had achieved everything that I had wished for myself. I had achieved honour, power, wealth, knowledge, and every human happiness. Then my desire for the increasing of these trappings ceased, the desire ebbed from me and horror came over me. The vision of the flood seized me and I felt the spirit of the depths, but I did not understand him. Yet he drove me on with unbearable inner longing and I said:

‘My soul, where are you? Do you hear me? I speak, I call you—are you there? I have returned, I am here again. I have shaken the dust of all the lands from my feet, and I have come to you, I am with you. After long years of long wandering, I have come to you again. Should I tell you everything I have seen, experienced, and drunk in? Or do you not want to hear about all the noise of life and the world? But one thing you must know: the one thing I have learned is that one must live this life.

‘This is the way, the long sought-after way to the unfathomable, which we call divine. There is no other way, all other ways are false paths. I found the right way, it led me to you, to my soul. I return, tempered and purified. Do you still know me? How long the separation lasted! Everything has become so different. And how did I find you? How strange my journey was! What words should I use to tell you on what twisted paths a good star has guided me to you? Give me your hand, my almost forgotten soul. How warm the joy at seeing you again, you long disavowed soul. Life has led me back to you. Let us thank the life I have lived for all the happy and all the sad hours, for every joy, for every sadness. My soul, my journey should continue with you. I will wander with you and ascend to my solitude.’

—C. G. Jung, The Red Book, Liber Novus

Image: © Philemon Foundation

and W. W. Norton & Company

Carl Gustav Jung (26th July 1875–6th June 1961) was a Swiss psychotherapist and psychiatrist who at the end of his thirties suffered an intense “confrontation with the unconscious”. Up until this point, life had rewarded him with everything he could possibly yearn for and yet all his outward accomplishments had left him feeling inwardly bereft.

Moreover, during his turbulent and unhappy childhood, Jung was able to perceive his mind as being both the source of his suffering as well as its panacea, developing two distinct and alternating personalities enabling him to cope: Personality No. 1, extraverted and interested in the ways of the world; and Personality No. 2., solitary and yearning for communion with the divine:

Naturally I compensated my inner insecurity by an outward show of security, or—to put it better—the defect compensated itself without the intervention of my will. That is, I found myself being guilty and at the same time wishing to be innocent. Somewhere deep in the background I always knew that I was two persons. One was the son of my parents who went to school and was less intelligent, attentive, hard-working, decent, and clean than many other boys. The other was grown up—old, in fact—sceptical, mistrustful, remote from the world of men, but close to nature, the earth, the sun, the moon, the weather, all living creatures, and above all close to the night, to dreams, and to whatever ‘God’ worked directly in him.

—C. G. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections

Image: Public Domain

Nonetheless, as he divorced himself from Personality No. 1 in order to experience a more authentic way of being exhibited through Personality No. 2, Jung realized that he lacked any coherent sense of a personal mythology, one by which he could navigate and fulfil his life’s purpose and direction, and which would lead him to actualization of the Self:

I was driven to ask myself in all seriousness: ‘What is the myth you are living?’ I found no answer to the question, and had to admit that I was not living a myth, or even in a myth, but rather in an uncertain cloud of theoretical possibilities which I was beginning to regard with increasing distrust … So in the most natural way, I took it upon myself to get to know ‘my’ myth, and I regarded this as the task of tasks—for—so I told myself—how could I when treating my patients, make due allowance for the personal factor, for my personal equation, which is yet so necessary for a knowledge of the other person if I was unconscious of it.

—The Collected Works of C. G. Jung, C. G. Jung, quoted in The Red Book, Liber Novus

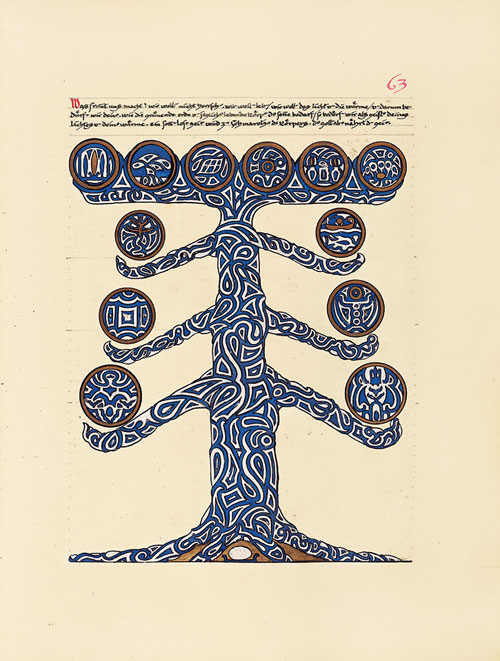

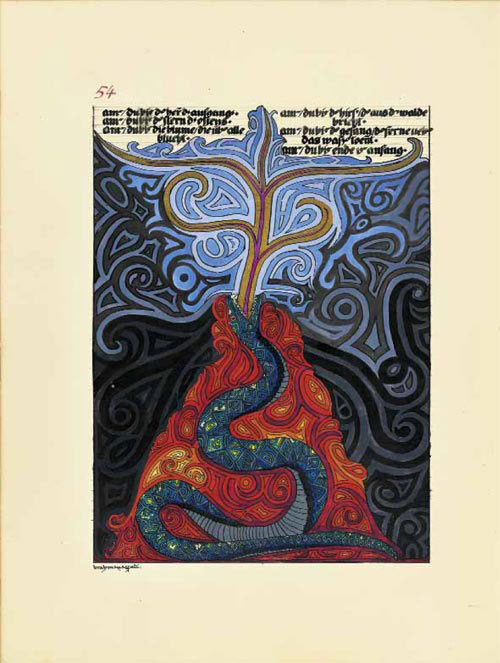

And thus, embarking on his own metanoia and drawing on his artistic talents developed as a child when he studied art and paitining, Jung started to record his inner fantasies into a series of six black journals, which he subsequently transcribed into a large, red leather folio, vividly illustrated with magnificent mandalas and mythological symbols, similar to a mediaeval manuscript in the manner of Hildegard of Bingen or the illustrated relief etchings of William Blake.

Image: © Philemon Foundation

and W. W. Norton & Company

I said to myself, ‘What is this I am doing, it certainly is not science, what is it?’ Then a voice said to me, ‘That is art.’ This made the strangest sort of impression upon me, because it was not in any sense my impression that what I was writing was art. Then I came to this, ‘Perhaps my unconscious is forming a personality that is not me, but which is insisting on coming through to expression.’ I don’t know why exactly, but I knew to a certainty that the voice that had said my writing was art had come from a woman … Well I said very emphatically to this voice that what I was doing was not art, and I felt a great resistance grow up within me. No voice came through, however, and I kept on writing. This time I caught her and said, ‘No it is not,’ and I felt as though an argument would ensue.

—Black Book 2, C. G. Jung, quoted in The Red Book, Liber Novus

Reminiscent to the Soliloquies of Augustine presented as an inner dialogue between himself and “Reason” who counsels the saint on the nature of his soul, Jung was in effect carrying on the genre of interior philosophical discourse by writing letters to his anima, the feminine aspect of his psyche.

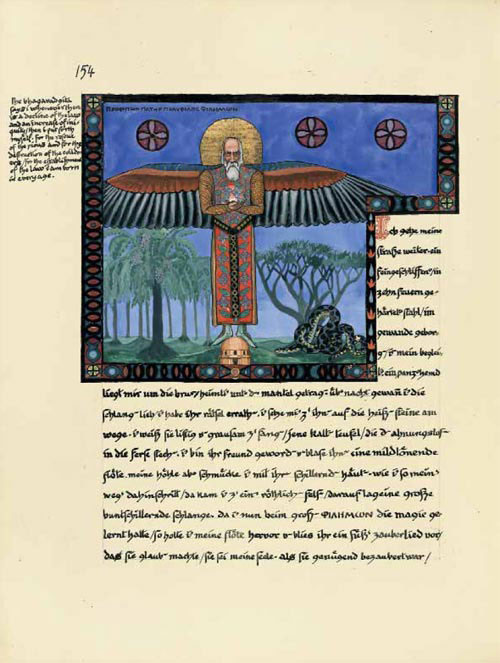

Moreover, being also deeply influenced by his close readings of Dante’s Commedia and Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, Jung similarly mirrors both their style and structure within his own work, utilizing the character of Philemon, a ghostly holy man with large, blue kingfisher wings, who emerges towards the end of the book as his mentor and guide.

Image: © Philemon Foundation

and W. W. Norton & Company

Indeed, Jung’s detailed and exacting self-analysis would inform the very basis of his unique approach to psychotherapy, which he would later call Analytical Psychology, its central tenet being the concept of “individuation”, an inner psychological transformation, whereby the personal and collective unconscious are brought into consciousness, through dreams and active imagination, and thus assimilated into the entire personality, rendering it into an integrated whole:

My soul spoke to me in a whisper, urgently and alarmingly: ‘Words, words, do not make too many words. Be silent and listen: have you recognized your madness and do you admit it? Have you noticed that all your foundations are completely mired in madness? Do you not want to recognize your madness and welcome it in a friendly manner? You wanted to accept everything. So accept madness too. Let the light of your madness shine, and it will suddenly dawn on you. Madness is not to be despised and not to be feared, but instead you should give it life … If you want to find paths, you should also not spurn madness, since it makes up such a great part of your nature … Be glad that you can recognize it, for you will thus avoid becoming its victim. Madness is a special form of the spirit and clings to all teachings and philosophies, but even more to daily life, since life itself is full of craziness and at bottom utterly illogical. Man strives toward reason only so that he can make rules for himself. Life itself has no rules. That is its mystery and its unknown law. What you call knowledge is an attempt to impose something comprehensible on life.

—C. G. Jung, The Red Book, Liber Novus

Despite the emotional turmoil that plagued Jung, forcing him to resort to yoga practices and even clinging on to the table in order to keep himself together, he persevered in compiling his artistic and literary magnum opus, knowing that the very salvation of his own soul was at stake.

Image: © Philemon Foundation

and W. W. Norton & Company

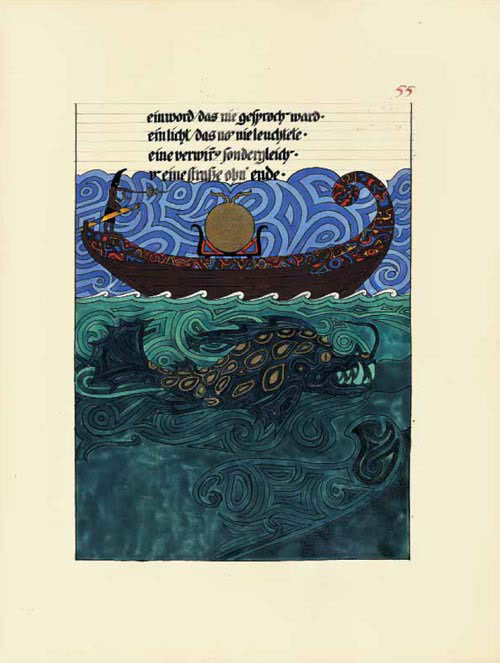

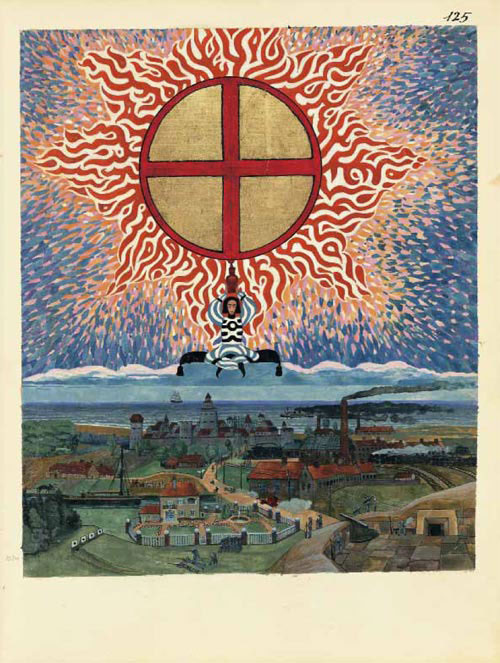

The Red Book is the zenith of Jung’s life achievements, enshrining a legacy of interlacing threads: self-knowledge; the interplay between the masculine and the feminine; learning and scholarship; the significance of symbols; madness; solitude; the nature of the human soul.

Moreover, it presents us with a schema of the individuation process itself, as the soul embarks on its passage, nekyia, to the psychic underworld, returning ever refreshed, rejuvenated and renewed. Indeed, in his therapeutic practice, Jung would encourage his patients to create their own mythology through writing and drawing and painting—to generate their very own Red Books:

I should advise you to put it all down as beautifully as you can—in some beautifully bound book … It will seem as if you were making the visions banal—but then you need to do that—then you are freed from the power of them … Then when these things are in some precious book you can go to the book & turn over the pages & for you it will be your church—your cathedral—the silent places of your spirit where you will find renewal. If anyone tells you that it is morbid or neurotic and you listen to them—then you will lose your soul—for in that book is your soul.

—Analysis Notebooks, C. G. Jung, quoted in The Red Book, Liber Novus

Image: © Philemon Foundation

and W. W. Norton & Company

Jung read widely in both Western mysticism and Eastern philosophy—even travelling to India in 1938—developing a bespoke psychological definition of the self, the archetype of wholeness, which he equated with the Hindu notion of Brahman/atman, though it always remained a theoretical ideal and something to which to be aspired, rather than the eternal, a priori reality already present within.

And yet The Red Book is no philosophical tract or erudite thesis embroiled in theory and platitude; it is the artistic unfoldment of one man’s profound inner journey through an alchemical creative process, culminating in a beauteous manifestation of transcendence, illumination and truth:

I, too, lived—which I had not done before, and which I could still do. I lived into the depths, and the depths began to speak. The depths taught me the other truth. It thus united sense and nonsense in me. I had to recognize that I am only the expression and symbol of the soul. In the sense of the spirit of the depths, I am as I am in this visible world a symbol of my soul, and I am thoroughly a serf, completely subjugated, utterly obedient. The spirit of the depths taught me to say: ‘I am the servant of a child.’ Through this dictum I learn above all the most extreme humility, as what I most need.

—C. G. Jung, The Red Book, Liber Novus

Post Notes

- T. S. Eliot: A Man Out of Time

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Eric Nicholson: William Blake’s Vision of the Book of Job

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- Spiros Stathoulopoulos: Meteora

- Rollo May: My Quest for Beauty

- Kahlil Gibran: Poet, Painter, Prophet

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- Albert Camus: Jonas or The Artist at Work

- Mark Rothko: The Artist’s Reality