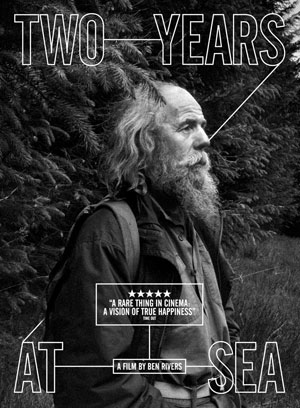

Ben Rivers, Two Years at Sea

Highlands hermit

We’re fed so much data, too much knowledge, too much information. I’m not interested in data. Obviously there’s some I want to know, but there’s an insistence that we need to be told everything and in a way that kills the imagination, which is a really important tool for humans. That’s one of the reasons why art is so important. I’m interested in making and watching films that can veer away from information and fact telling, so you’re not being told everything at every turn.

—Ben Rivers

IF I HAD to choose one film that had the capacity to convey cinematically the quintessential element of silence, that all-pervasive, mystical quality of “isness” saturating land and lake and lumber, Two Years at Sea would be my only and everlasting selection. Elegant and melancholic, Ben Rivers’ masterpiece exudes a quiet, minimalistic beauty, rarely seen in contemporary screenings. Indeed, such is its elegiac aesthetic, I have to pause the play button in order to momentarily compose myself as I am overtaken by its artistic refinement and oneiric grace.

Photograph: © Ben Rivers

Shot on an antique Bolex camera using black and white 16mm film stock, Two Years at Sea is an impressionistic portrait of Jake Williams, who lives a solitary life in a tumbledown farmhouse in the Cairngorms, a mountain range in the eastern Highlands of Scotland. With no discernible plot or narrative, we witness an eremitic man, hirsute and careworn, going about about his daily business seemingly without a care in the world.

Ordinarily, a filmmaker might be hard pushed to engage the viewer for over an hour’s worth of footage with negligible action and dialogue (“chesty cough” are the only words muttered within its 88 minutes’ duration as Williams examines a medicine bottle) and yet when we consider John Cage’s observation—“If something is boring after two minutes, try it for four. If still boring, then eight. Then sixteen. Then thirty-two. Eventually one discovers that it is not boring at all”—Rivers has taken this exemplum to its zenith whereby boring is transmuted into captivating, mysterious and utterly unique.

Photograph: © Ben Rivers

Originally, Rivers had made a much shorter piece entitled This Is My Land about Williams a few years earlier, which can now be viewed as a prelude to Two Years at Sea enabling his daily activities and rituals—making coffee, washing clothes, chopping wood—to be engaged with in their entirety, the effect being that we become completely engrossed with the task at hand, not unlike observing a Zen Buddhist practice, bringing us into the present moment and a life lived in the here and now.

In one particular sequence, in which Williams constructs a makeshift raft with plastic canisters and then floats off nonchalantly upon a calm stretch of icy-cool water (hinting at the seafaring years of the film’s title), the aperture exposure period is approximately ten minutes. As we watch transfixed, time slowly evaporates into the timeless as we similarly drift away upon a swell of mutually-shared stillness.

Photograph: © Ben Rivers

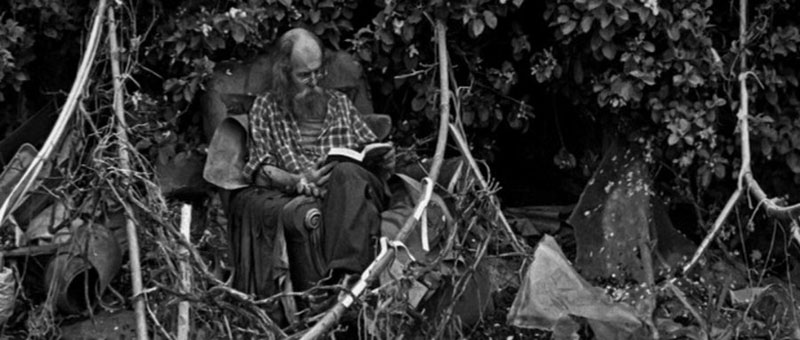

Despite moments of achingly beautiful scenery, the film never descends into the sentimental or precious; Williams’ cottage is a hoarder’s paradise, stuffed to the gunnels with appliances and objects in various states of disrepair. In one truly lovely moment, Williams is washing his clothes in an old, open twin-tub laundromat, his black cat perched atop a stool before it; utterly mesmerized, its inquisitive ears twitch back and forth in tune with the throb of the drum.

Elsewhere, we see books, letters, maps, vinyl records, photographs and other memorabilia alluding to an enigmatic past but one which is never explained. There is no requirement, nonetheless, to understand Williams’ history for all we need really concern ourselves with is a man represented to us who, despite being surrounded by the chaotic detritus of articles and gadgets, lives unencumbered by the ways of the world and an identity with a forsaken former life.

Ben Rivers, This Is My Land

An art-school graduate, Rivers has made over 30 short films to date, his repertoire leaning more and more towards sci-fi and post-apocalyptical societies, as well as outsiders living far removed from normal civilization as we know it. Furthermore, drawing on classic literature, such as Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis and the Norwegian author Knut Hamsun’s novel, Pan, which concerns a man who lives alone in the forest, Two Years at Sea is the apogee of Rivers’ preoccupation with solitariness and the independent life.

We must ultimately remember that the film lies along the magical cusp where fact and fiction intersect and that Williams’ role is, according to Rivers, an “exaggeration”, who he directs like an actor to perform specific shots. Touches of surrealism also abound, particularly when one of Williams’ caravans miraculously levitates up into the air, hovering tentatively above the treetops like an Arabian fable from The One Thousand and One Nights. Opening the door after his daily constitutional nap, Williams surveys the Aberdeenshire landscape from his newly elevated position, seemingly nonplussed, as if still ensconced within a dream.

Photograph: © Ben Rivers

As we bear witness to the changing seasons, the artisanal hallmarks of Rivers’ hand-processing—burns and bubbles and scratches—render an ever deeper quality to the overall aesthetic experience, whereby the celluloid itself encapsulates the very nature of the elements he is trying to represent: watermarks flicker over thunderclouds; light flares dance across a luminescent sky; grain pulsates in rhythm with a snowstorm. In the manner of American avant-garde cinematographer, Stan Brakhage, the physicality of the medium is quite literally part and parcel of Rivers’ art.

Indeed, Rivers joins an elite coterie of auteurs, including Béla Tarr, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Jean Cocteau, Andrei Tarkovsky and Michelangelo Antonioni who champion the depiction of beauty over and above everything else. The fact that Two Years at Sea won the prestigious FIPRESCI Award at the Venice International Film Festival in 2011 bears testament to such an illustrious inheritance.

Photograph: © Ben Rivers

As far as I am aware, Rivers has no specific metaphysical agenda to his work; and yet, for me at least, Two Years at Sea is suffused with such ineffable meaning, majesty and mystery, it evokes a deeply spiritual response. Perhaps it is the humble simplicity of Williams’ existence; the monochromatic gracefulness of Rivers’ filmmaking; the evocation of an effortless, unbounded silence that infiltrates the very depths of your being long after the final frame.

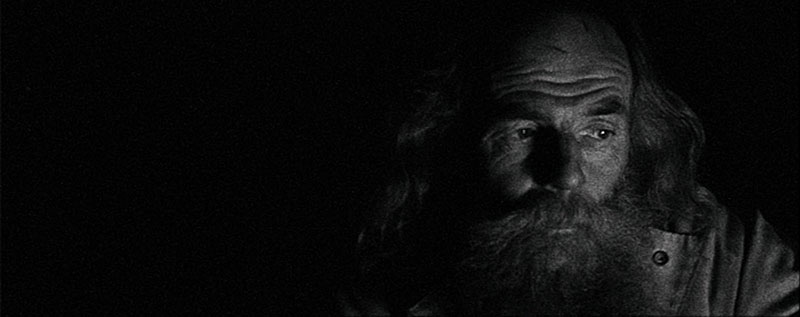

The closing shot is another extended take of Williams, lost in reverie before the dying flames of a sputtering fire. Shadows sculpt his weather-beaten features as we try and scrutinize the thought patterns of his mind. Perhaps he is thinking about nothing in particular—even mental commentary is extraneous to the film’s unfoldment it would seem—as the darkness stains Williams’ profile and his form is obliterated by the void. As with each and every viewing in which I partake of this spellbinding visual poem, I too feel my own identity sail away, finally submerging unto an omnipresent, undifferentiated sea.

Photograph: © Ben Rivers

With a lot of my films over the years I’ve been interested in spaces and objects as a way to build a portrait of a person, an understanding of who they might be without that straightforward telling. So that’s the strategy for Two Years at Sea, to give the audience these clues to a past. There’s still plenty of room to decide who the person in that photograph is, or where an object or a piece of music comes from. So the Indian music in the film is significant to Jake’s life, there’s a reason why it’s there; it’s music he bought when he was working as a merchant seaman and going to markets. I like the idea that you don’t have to know all the answers and it’s fine not to know. You’re still getting a pretty intimate view of someone but it’s a moment in time.

The rest of it you can think about because you’re never going to find out everything about a person. Even if I made a really straightforward documentary with loads of talking and everything explained you’re still never going to know the person. I’m much more interested in making something that is not necessarily about that person. I’m interested in working with that person collaboratively to make something new, to make something that exits just for itself.

—Ben Rivers

Post Notes

- Ben Rivers’ website

- Ben Rivers on Vimeo

- The White Review interview with Ben Rivers

- Jean Cocteau: The Art of Cinema

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinematic Genius

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul: Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Paula Marvelly: A Singular Man

- Carlos Reygadas: Japón

- Carl Theodor Dreyer: Ordet

- Abbas Kiarostami: 24 Frames

- Kaneto Shindo: The Naked Island

- Maya Deren: A Study in Choreography for Camera

- Lisandro Alonso: Jauja