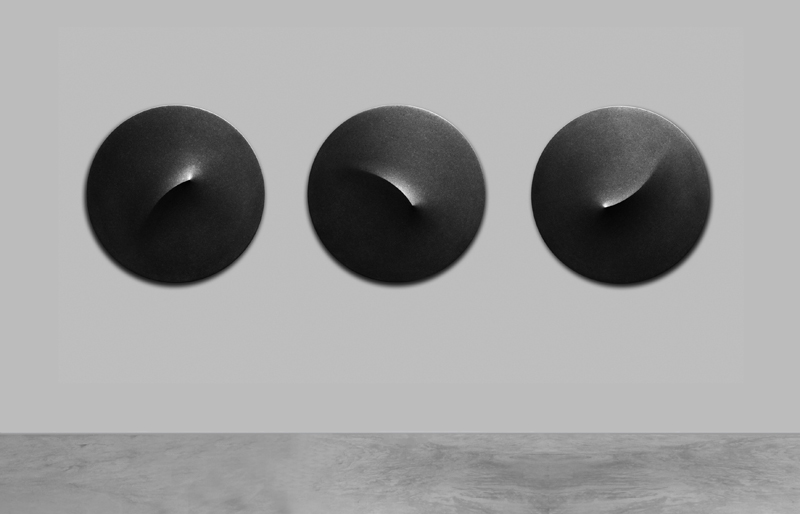

Photograph: © Stefano Baroni

Transcendentally charged

“For me, the process of sanding and polishing is to cancel out the working marks,

my traces, my ego, myself, until it becomes an independent entity.”

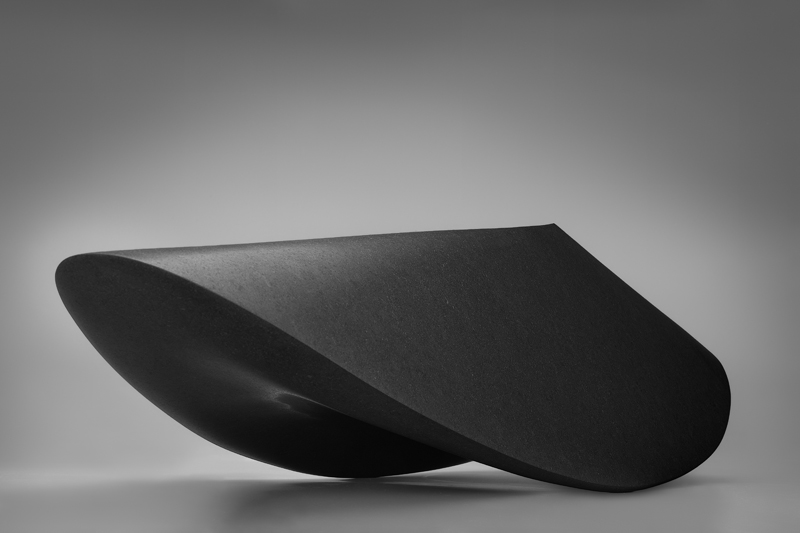

ARMEN AGOP is a multi-award-winning Egyptian artist of Armenian origin, who is best known for his spiritually charged paintings and sculptures. Working with elemental entities—black granite or canvas and ink—his creative offerings can be perplexing, often appearing as futuristic beings or UFOs, and yet simultaneously reminding us of the soberness of ancient Egyptian art with its powerful lines and simple formations.

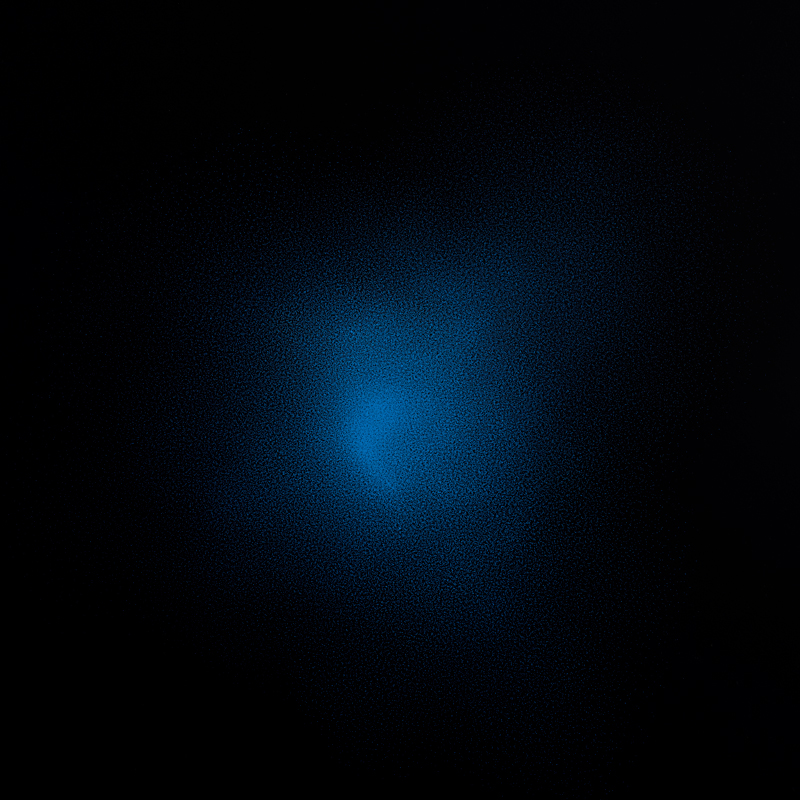

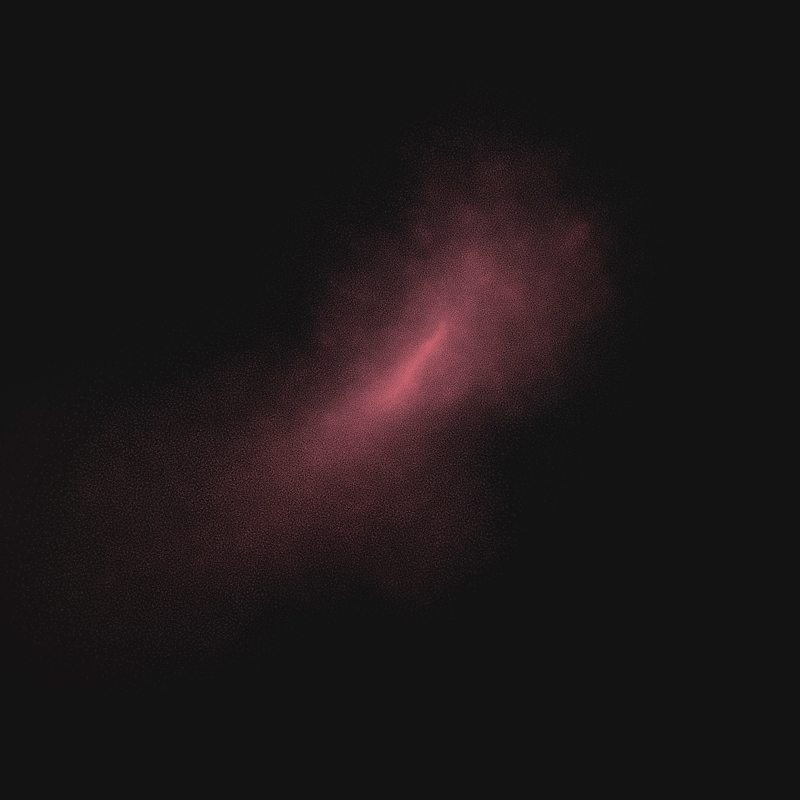

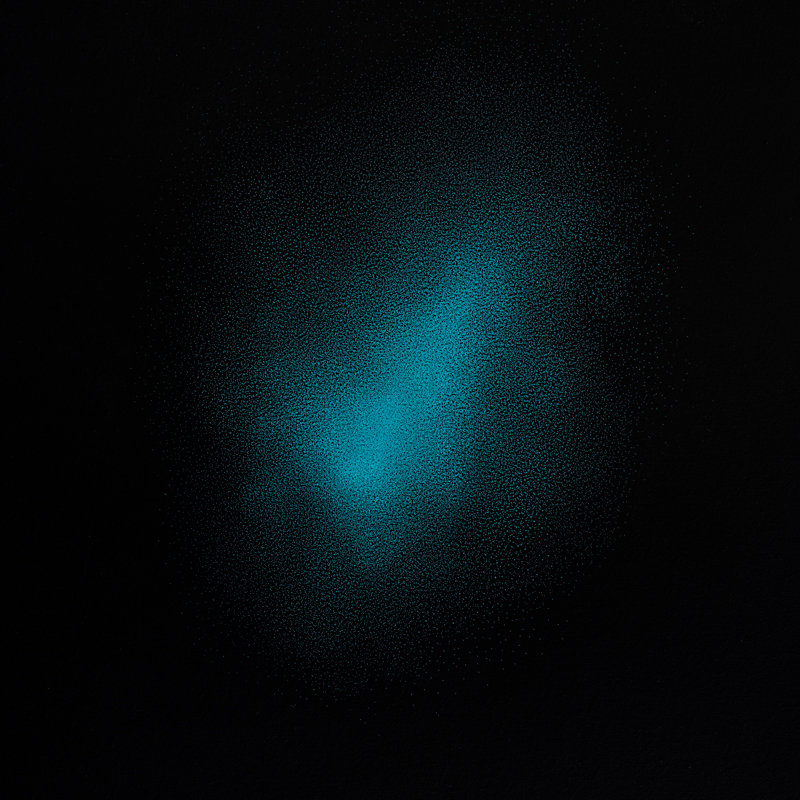

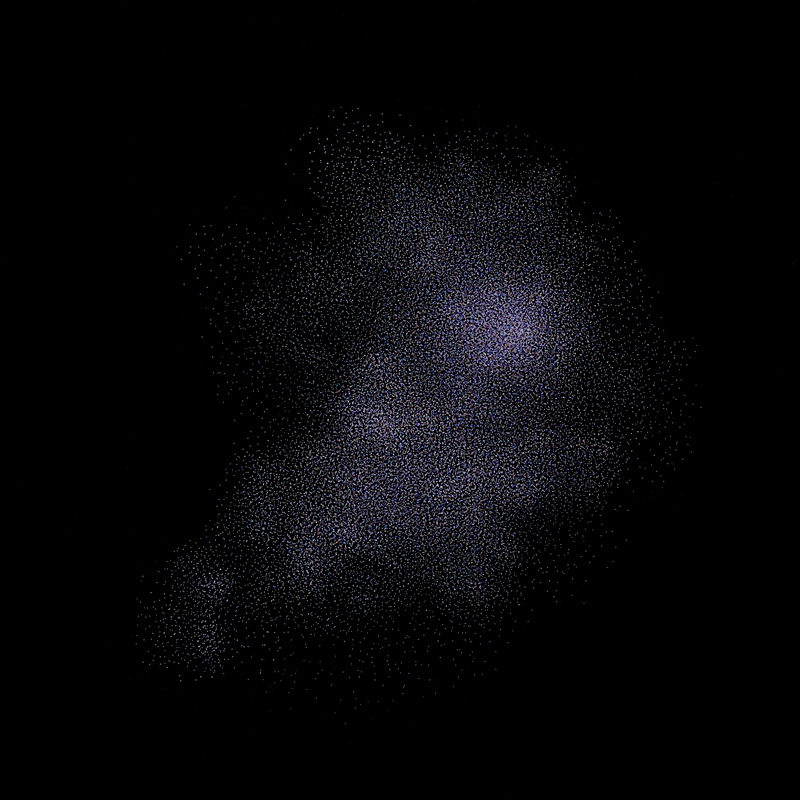

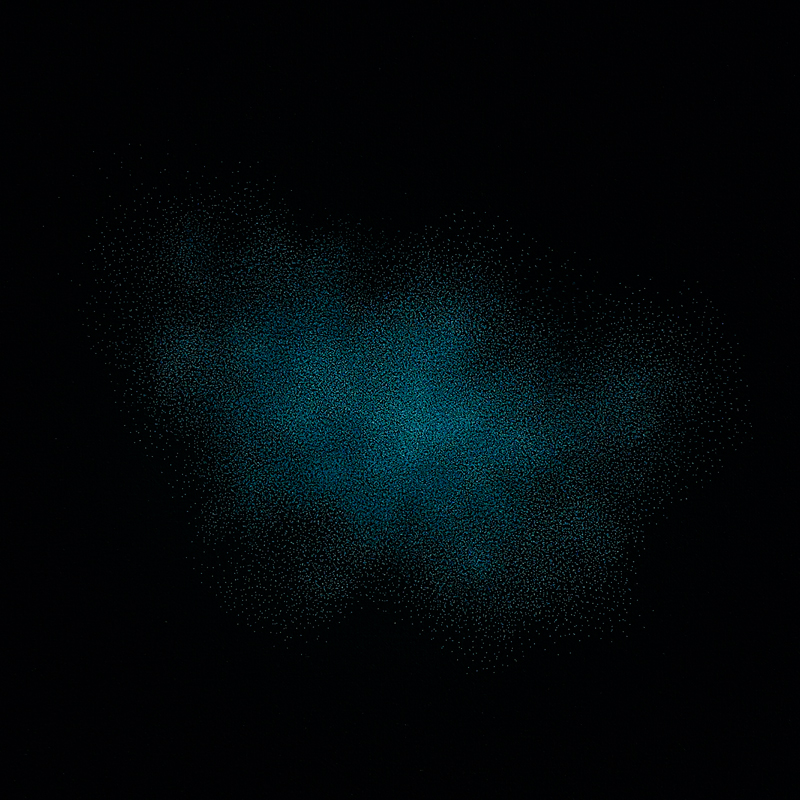

Describing in his own words his obsessive process being analogous to a contemplative practice, Armen’s latest paintings—recently showcased in the Taking Time exhibition at the prestigious Flora Bigai Arte Contemporanea gallery—are luminescent galaxies of points upon a black abyss, the act of composition akin to a meditative mantra, emerging and evolving through the passing of time, distilled in the very timelessness of his art. He currently lives and works in Pietrasanta, Italy.

Photograph: © Stefano Baroni

The dialogue we have with ourselves reflects our inner world. I believe the questions that artists ask themselves are the tangible differences perceived in their work. During our practice, we find ourselves in front of many questions and possibilities, so we come up with answers and make choices. The answers may change during a lifetime, questions too. Sometimes I realized I didn’t need to ask the question; I learned that there was nothing to understand. We tend to understand and misunderstand what many times doesn’t need to be understood, it just needs to be perceived.

I used to ask myself why humans go through sacrifices and insist on creating things that no one asked for or cares about. Looking at myself and what made me take this path, I see that I just drew, like any child, and never found a good reason to stop (I don’t know why others did). I played with lines, colour and form. Reaching a certain age, we discover that society calls that play, art, and those who practise it, an artist.

Photograph: © Meem Gallery

I still remember as a young teenager I went on a fishing trip with some friends to the countryside on the river Nile. I didn’t come back with any fish but I came back with a piece of limestone I found on the shore. I didn’t know why, it didn’t make sense to carry it all the way back and what was I going to do with it? I discovered that later, when I sculpted a portrait from it with the only tool that existed at home—a screwdriver.

I came back from that trip not with fish but with a whole universe, a discovery of a new instinct, even if I wasn’t aware of it at that time. So I realized that, in my case at least, it is simply an instinctive drive. That’s my way of being. When I am playing/doing/working, I am simply existing in my way. I believe artists are the ones who can’t ignore their instinctive drive.

I still continue playing. What I do in the studio is to follow instincts and interests. I explore and try to enjoy and discover and then maybe, during play, I come to something that intrigues me, something I believe in and then I can’t stop pursuing it obsessively. I carry on, blindly digging deeper, with an unexplainable belief, without any evidence that it can reach something interesting or valuable. Many times, it’s completely irrational, it becomes a matter of faith. Like a practice of praying. I believe that all art is playing seriously. I don’t work; I either play or pray.

Photograph: © Francesco Pelosi

A question that I never asked myself—as I just followed my instinct—but others have often asked, so it’s made me reflect, is: why granite?

I have a very intimate and obsessive relationship with granite. We complement each other. Granite is an ancient material that existed before us, so it is not accustomed to change very often or quickly; its hardness and compactness require time and slowness. So the slow process gives me time to discover what I really want to share with the material. Because it’s not only about what I want to do, it’s about what agreement we come to. It’s a meeting between me and another part of nature, the granite. Any piece of granite that you may see in nature stands with a certain pride, its presence dominates the surrounding space. It came out from the core of the globe, I believe for a reason, so to interfere with such an honourable part of nature is a big responsibility.

Photograph: © Stefano Baroni

And then the question arises, what sculpture would be worthy of transforming the nature of such a character like granite?

Our ancestors consistently engaged with stone, from creating their homes in the caves to tombs, from hunting tools to surviving/killing tools, from the gods to devils, from life to death. With such a connection, obviously, it can’t be interrupted easily. Somehow, I refer my obsessive relationship with granite to all of our past, with all our experiences and rituals. Granite requires a slow process, practising repetitive movements, which hardly show any progress. Praying and ritual habits usually consist of repetitive phrases, or in my case, gestures. This helps me to unite with myself first and then with the material.

Photograph: © Stefano Baroni

The human being has been very egocentric throughout history and the art of humans has been very self-centred; we created gods from our own likeness and devils, too. For a long time, the human mind limited the universe to itself. For me, a sculpture is an entity that somehow should be able to relate to the whole globe, as the globe is in relationship with a galaxy and the galaxy with the cosmos.

It is about extracting something from our interior universe through time and matter to the outside world, materializing the immaterial. By understanding that, I came to believe that art is beyond meaning. It transcends the individual and goes beyond you and me. So, I was driven to deprive my sculptures of any references, any trace of human gesture. My concern focused on articulating silence. So from self-centredness to self-renouncement.

Photograph: © Stefano Baroni

But is granite real matter? Granite requires time and for me, the most important aspect is the time spent between me and the material. The slowness and repetitive movements became rituals. A meditative aspect developed as part of my unification with the matter. The real matter became time. For me, it is not only about the form itself but about the connection between the interior world and the exterior universe.

The process of time and my ascetic approach developed more and more to a meditative process whereby choosing the smallest element possible, a point (0.1 mm pen tip), and applying it on a canvas, repeating it endlessly without lofty plans or pretentious claims, became a personal mantra, a gestural mantra. The point transcends from being a hermit and solitary in the sculptures to a member or part of a cosmic society, without losing its soberness or dignity on the paintings.

Photograph: © Stefano Baroni

Ancient, Contemporary or Transcontemporary? Having contact with many artworks from diverse periods of time, I wondered why I engaged with some works regardless of their historical time, both recent and ancient.

I believe that authentic art is timeless, it’s Transcontemporary. An artist is someone who is loaded with an authentic human experience and is able to discharge it through whatever medium—a stone, a word, a tone—but that’s not important; what’s important is that the matter remains charged and keeps on charging whoever comes into contact with it.

Photograph: © Giovanni Romboni

An artwork is a container of a human experience. A poem in a closed book is contained energy, ready for whoever reads it, wanting to be charged. Art is able to energize a part of us that is usually ignored. In my experience, the artworks that touch us deeply and manage to connect with us are artworks that have a rich internal world and vital inner connectivity with themselves. The hard part is the ability to detect it because it’s not about the obvious elements in an artwork; most of the time, it is about what is beneath that which is evident. It’s the unseen, the invisible. I believe that the appearance of the artwork is a big obstacle. We call it visual art but it’s all about the invisible.

Answers without questions … It was in the desert, where there seems to be nothing; that’s where I learned to see.

Photograph: © Francesco Pelosi

In front of every blank canvas or paper, I face nothingness. What breaks it is the desire of doing. With each blank paper, there is a new unknown to explore, a nothingness to go through. By doing it more and more, a hidden part of me is unveiled. After some time, it isn’t about me anymore but about the whole universe. By exploring my nature, I explore the universe’s nature. We are one. Each painting is a cosmic one, even if it’s a failure. When I make a painting, the painting makes me too.

When I shape a stone, in a way, I am reshaped. What we touch, touches us. It’s never only physical, even if we are not aware of it. I think artists are privileged, even when poor and unnoticed or unsatisfied, yet they still have the chance (while working or playing) to experience a moment of cosmic engagement. Because every authentic work of art is a cosmic event. Beyond time, beyond meaning and beyond self.

Photograph: © Giovanni Romboni

By exhibiting in many parts of the world, I have been surprised by the different responses of the viewer and I wondered why. In the East, for example, my work was attributed to Zen; in Scandinavia, they see it according to their pure design aesthetics; in the Middle East, to Sufism and asceticism.

So I realized that every culture reflects itself in what artists do and how they see it. Art unveils a hidden part of ourselves and revives the way we want to see the world. I think the silence in the work allows the viewer to exhale their inner world in the perceiving process.

Photograph: © Flora Bigai Arte Contemporanea

Post Notes

- Armen Agop’s website

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Henry David Thoreau: Walking

- Antony Gormley: Sculpted Space Within and Without

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Philip Jacobs: Dance of the Dervishes

- Rollo May: My Quest for Beauty