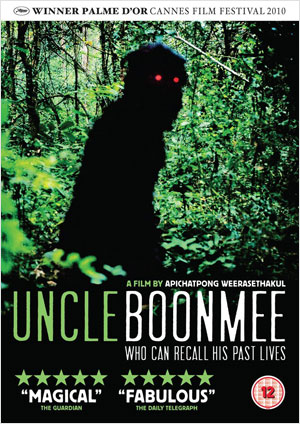

Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives

Facing darkness, finding light

“Deep down, I know that reflection is an illusion. Is it an illusion?”

“You’re the same person I’ve always revered.”

“That’s an illusion too.”

THERE IS SUCH beauty, profundity and elegance about auteur Apichatpong “Joe” Weerasethakul’s (born 16th July 1970) magical masterpiece that, like a meditation practice, upon repeated reviewing it yields ever deeper realms of spiritual illumination and wonder.

Winner of the prestigious 2010 Palme d’Or at Cannes, the film draws inspiration from the true account of a man simply named Uncle Boonmee, who had recounted to a Buddhist abbot the memories of his past lives as he prepared for his imminent death. Blending political references to a 1960s’ Communist uprising as well as personal recollections of his own father’s passing, Weerasethakul’s Uncle Boonmee is the tale of a successful hill farmer, diagnosed with acute kidney failure, who has returned home to the Thai countryside in order to die surrounded by his family and close friends.

Fantastical and dreamlike, this is a love letter to magical realism at its most magnificent; believing his fatal illness to be the result of bad karma, Weerasethakul’s protagonist is visited by the ghost of his deceased wife and his long-lost son, in the form of a monkey spirit, both coming to nurse and support him during the transmigration of his soul into a future self.

Photograph: Strand Releasing

Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives is one of the most sublime and utterly spellbinding pieces of cinematic art I have ever experienced. From the outset, we are mesmerized by a mystical realm populated by humans and ghosts and animals, whereby the boundaries between life and death are blurred, and all is not quite what it seems.

Drifting from one remembrance to another, the film beguiles us with its stream of consciousness montage. The ambient soundtrack—the pulsing of cicadas, the susurration of foliage, the thrumming of bees—lulls us into a somnolent stupor, surrounded by transmigrating spirits and reincarnating souls.

It is a mysterious and mythological dreamland and yet palpably counterpointed with the very real and modern threat of cultural annihilation and the haunting danger of prospective military action.

Photograph: Strand Releasing

Structured itself like a series of past lives, each major sequence is shot in a specific cinematographic élan. The opening chapter of a bull sniffing the twilight air, then breaking free of its tether to run loose through a lush meadow, is slowly and sumptuously filmed, with shades of Andrei Tarkovsky; its overall significance left to linger in the subterranean layers of our minds.

A later scenario involving a family evening meal is staged as the set of a 16mm TV drama, with precise posturing and formal lighting, framed within crisp and well timed dialogue. Here we meet the arrival of Boonmee’s dead wife, who materializes out of thin air; notwithstanding their initial surprise, she is then welcomed like an expectant dinner guest and asked, somewhat ironically, “You must be hungry.”

And then towards the end of the film, a series of still photographs, both macabre and humorous, of teenage soldiers holding Boonmee’s tethered monkey son, captured in a dystopian future, evoke the iconic La Jetée by Chris Marker in their static and prophetic vision of a totalitarian society yet to come.

Photograph: Strand Releasing

The most poignant and yet utterly surreal sequence unfolds in a moonlight scene set by a waterfall. A disfigured Thai princess, lamenting the loss of her youth and beauty, gazes into the pool, whereupon her reflection is transmuted into a lithe and attractive young woman. She then instructs her male servant to embrace her, which he dutifully enacts, albeit without any feeling or eye contact.

The princess is understandably devastated and sends him away, collapsing in grief by the pool. Through her tears, she discerns a male voice arising from the watery deep, telling her that she is blessed with inner beauty way beyond her female counterparts.

Transfixed by the aqueous spirit, manifesting in the form of a catfish, she immerses herself into the water, jettisoning jewellery and casting off clothing, whereupon she is seduced in a swirling surge of bubbling evanescence. What does it all mean? We are left bewildered only if we stop to ponder its significance; akin to Terrence Malick’s, The Tree of Life, the aesthetic beauty of the scene is bewitching enough.

Photograph: Strand Releasing

In the final chapters, Uncle Boonmee treks through the jungle with his family to a secluded cave atop a mountain, the birthplace of his first life, in preparation for his journey to his next embodiment. The chamber is encrusted with crystals, which glisten in the light of his torch. As he settles down in the darkness, the red eyes of monkey spirits radiate in the far reaches of the forest. By sunrise, Boonmee will be gone.

Despite all the supernatural elements, Uncle Boonmee is a deeply human film. Ironically, it is the very simplicity of living—watching TV, eating honeycomb, killing moths—that elevates it into a deeply poetic testament of the very nature of mortal existence, augmented by the choice of non actors for the lead roles.

And yet, just as John Cage exhorted us to dwell on the seemingly mundane and inconsequential in ever-increasing temporal increments, by the act of our lingering on the ordinary a little while longer, Apichatpong Weerasethakul transports us to the realm of the extraordinary and beyond, indeed towards the transcendental life and spirit of the very universe itself.

Post Notes

- Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s official website, Kick The Machine

- Strand Releasing

- Terrence Malick: The Tree of Life

- Ben Rivers: Two Years at Sea

- Kim Ki-duk: Spring, Summer, Autumn, Winter … and Spring

- Carl Theodor Dreyer: Ordet

- Lisandro Alonso: Jauja