Antony Gormley, Sculpted Space Within and Without

The art of Consciousness

“It’s wonderful to see art in a museum but it is institutionalized. I don’t like the idea of the artwork as something that requires special conditions. I would like it to be universal.”

A FEW YEARS AGO, I lived for 18 months or so in a caravan in the south of France. Despite being at the bottom of my parents’ garden, I was to all intents and purposes isolated from the rest of the world. It sounds bohemian in many respects and yet it was a deeply challenging experience—my parents were both very poorly at the time (and hence the reason why I was there in the first place) and the extremes of temperature (from 50 degrees Celsius to sub zero) coupled with the resident wildlife (spiders, snakes, mosquitoes, ants, plus the occasional feral cat) nearly drove me insane.

By far and away the most taxing element of the experience, however, was the enforced solitude for hours at a time, ticking by relentlessly and predictably day after day, like the ebb and flow of the sea. As Antony Gormley says in his inspirational talk, which still remains to this day my favourite TED presentation of all, I initially dreaded the singular confinement in such an intemperate sarcophagus-like space, with only my thoughts as companions and confidantes.

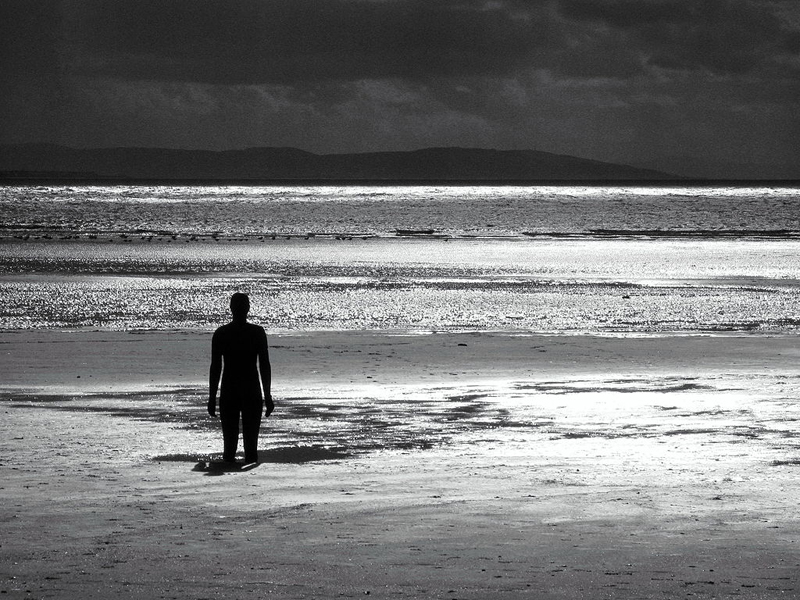

Photograph: Keith Page, [CC BY-SA 2.0] Wikimedia Commons

When I was a child—I don’t know how many of you grew up in the ’50s—I was sent upstairs for an ‘enforced rest’. It’s a really bad idea. I mean, after lunch, you know, you’re six, and you want to go and climb a tree. But I had to go upstairs to this tiny little room that was actually made out of an old balcony. It was incredibly hot, small and light, and I had to lie there. It was ridiculous! But anyway, for some reason, I promised myself that I wasn’t going to move, that I was going to do this thing that Mummy wanted me to do. And there I was, lying there in this tiny space, hot, dark, claustrophobic, matchbox-sized, behind my eyes … But it was really weird—after this went on for days, weeks, months, that space would get bigger and darker and cooler until I really looked forward to that half an hour of enforced immobility and rest, and I really looked forward to going to that place of darkness.

—Antony Gormley, TED Talk

The French philosopher, Blaise Pascal, in his Pensées, famously said, “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” And he’s right. It is the perpetual yearning for sentient and sensory experience beyond the confines of our immediate position, in front of our eyes as it were, that drives our restless being into emotional pain and psychological purgatory. For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his own soul?

Like Gormley, the enforced rest in my caravan meant I similarly had to face myself, embrace the inner darkness, and thus, I too came to love the immobility and silence of my condominium cell where, paradoxically, a rich interior life was revealed to me and The Culturium website was born.

Photograph: Chris Howells, [CC BY-SA 3.0] Wikimedia Commons

Do you mind if we do something completely different? Can we all just close our eyes for a minute? Now, this isn’t going to be freaky. It isn’t some cultic thing. It’s just I would like us all to go there. I’m going to do it too. We’ll all be there together …

So close your eyes for a minute. So here we are, in a space, the subjective, collective space of the darkness of the body. I think of this as the place of imagination, of potential, but what are its qualities? It is objectless. There are no things in it. It is dimensionless. It is limitless. It is endless.

Okay, open your eyes …

That’s the space that I think sculpture—which is a bit of a paradox since sculpture is about making material propositions—but I think that’s the space that sculpture can connect us with.

—Antony Gormley, TED Talk

Educated at a Benedictine boarding school and then the University of Cambridge where he read Archaeology, Anthropology and the History of Art, Sir Antony Mark David Gormley, OBE (born 30th August 1950) travelled to India and Sri Lanka to learn about Buddhism before returning home to complete his sculptural studies at Saint Martin’s School of Art and the Slade School of Fine Art in London.

Across a career spanning more than 40 years, he has used sculpture as a means to examine the human condition not only in its relationship to space and time but also to investigate the noumenal nothingness in which everything in creation is contained. Moreover, explaining how his strict Catholic childhood and his subsequent search for illumination in the Indian subcontinent influenced his decision to become an artist and sculptor, he said: “If you are brought up a Catholic you may lose your Catholicism but the fact is it has marked you for life. And the need to replace its belief system with something else becomes your life’s work.”

Photograph: Ian Mcallister, [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Dark matter now placed against a horizon … If minds live in bodies, if bodies live in clothes, and then in rooms, and then in buildings, and then in cities, do they also have a final skin, and is that skin perceptual?

The horizon …

Is art about trying to imagine what lies beyond the horizon? Can we use, in a way, a body as an empty catalyst for a kind of empathy with the experience of space-time as it is lived, as I am standing here in front of you trying to feel and make a connection in this space-time that we are sharing? Can we use, at it were, the memory of a body, of a human space in space to catalyse a firsthand experience of elemental time?

—Antony Gormley, TED Talk

Indeed, the spiritual component of Gormley’s work, none so beautifully personified than the human sculptures intermittently submerged in the spuming sea as part of the installation, Another Place, move me so very deeply that I yearn to stand right next to them and discern what exactly it is that holds them transfixed as they stare, unwaveringly, out to the ocean’s seam.

Like silhouetted bodhisattvas, their inner resolve and stillness evoke an intuitive desire to dive deep within our very own inner selves to dissolve unto the darkness and reconnect with the limitless and dimensionless space of the elemental void.

Photograph: Andrew Dunn, [CC BY-SA 2.0] Wikimedia Commons

For me, art is not about objects of high monetary exchange. It’s about reasserting our firsthand experience in present time. As John Cage said, ‘We are not moving towards some kind of goal. We are at the goal, and it is changing with us. If art has any purpose, it is to open our eyes to that fact.’

—Antony Gormley, TED Talk

I am utterly unable to connect wth most post-modernist art—be it the visual arts, performing arts or literature—that champions art for art’s sake, devoid of anything sacred or profound or meaningful. And yet, once in a while, a pharos of brightness produces a body of work of such artistic creativity, imbued with an inner wisdom, that I thank God for these aesthetic alchemists who walk amongst us, blessing us and bestowing us with their transcendental light.

Post Notes

- Antony Gormley’s website

- Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui & Antony Gormley: Sutra

- Paolo Sorrentino: The Great Beauty

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Ron Rosenstock: The Invisible Light

- Jerry Katz: Let the Scene See You

- John Ruskin: On Art and Life

- Danila Tkachenko: Escape

- John Cage: Silence

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Guy Laramée: Onde Eles Moram

- Bill Viola & Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Anna Gillespie: Give Me Shelter