How Russian filmmaker turned movie-making into transcendental art

“What is art? Like a declaration of love: the consciousness of our dependence on each other. A confession. An unconscious act that nonetheless reflects the true meaning of life—love and sacrifice.”

HAVING BEEN FAIRLY bookish all my life, I only came to the work of Andrei Tarkovsky well into my forties, I am ashamed to admit. And yet perhaps that wasn’t such a bad thing after all, in that my maturer, artistic sensibility was able to appreciate the overarching beauty and subtlety of Tarkovsky’s films far greater than my younger, more naïve self.

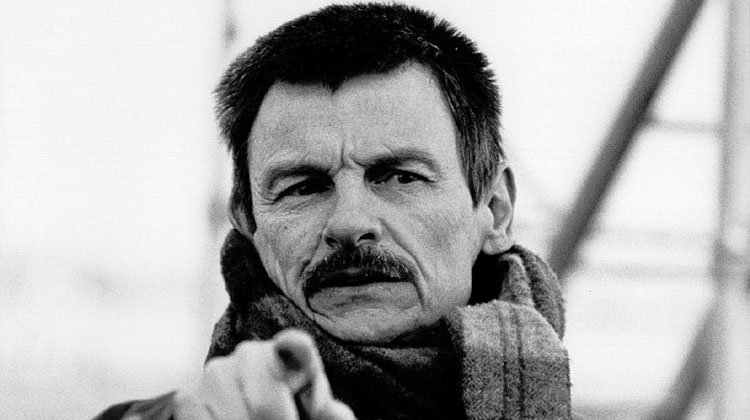

Andrei Arsenyevich Tarkovsky (4th April 1932–29th December 1986) was a Russian writer and filmmaker, film editor and theorist, theatre and opera director. His films are some of the greatest of all time: Ivan’s Childhood, Andrei Rublev, Solaris, Mirror, Stalker, Nostalghia and The Sacrifice.

Tarkovsky’s work reflects a deep preoccupation with the metaphysical and the spiritual realms, as well as unconventional dramatic structure and a distinctively unique use of the cinematic lens. Indeed, Ingmar Bergman, the Swedish filmmaker, said of him:

Tarkovsky for me is the greatest [director], the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream.

Photograph: Festival de Cine Africano de Córdoba, [CC BY-SA 2.0] Wikimedia Commons

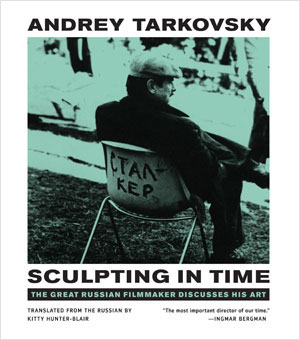

Sculpting in time

Tarkovsky felt a particular dissatisfaction for the increasing popularity of rapid-cut editing and other gimmicky montage techniques, which detracted from the true poetic spirit of cinema: “The dominant, all-powerful factor of the film image is rhythm, expressing the course of time within the frame.”

And thus, coupled with his fascination with all things transcendental and dreamlike, Tarkovsky compiled, Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema, a remarkable literary revelation of both his work and life, and which was completed shortly before his death in exile in Paris.

Reading Tarkovsky’s artistic testament renders an even deeper insight into the raison d’être behind his work than watching his films alone. Here, he is talking about “Art—a yearning for the ideal”:

Before going on to the particular problems of the nature of cinematic art, I feel it is important to define my understanding of the ultimate aim of art as such. Why does art exist? Who needs it? Indeed, does anybody need it? These are questions asked not only by the poet, but also by anyone who appreciates art—or, in that current expression all too sympathetic of the twentieth-century relationship between art and its audience—the ‘consumer’ …

In any case it is perfectly clear that the goal of all art—unless of course it is aimed at the ‘consumer’, like a saleable commodity—is to explain to the artist himself and to those around him what man lives for, what is the meaning of his existence. To explain to people the reason for their appearance on this planet; or if not to explain, at least to pose the question …

In a very real sense every individual experiences this process for himself as he comes to know life, himself, his aims. Of course, each person uses the sum of knowledge accumulated by humanity but all the same the experience of ethical, moral self-knowledge is the only aim in life for each person, and subjectively, it is experienced each time as something new.

Again and again man correlates himself with the world, racked with longing to acquire, and become one with, the ideal which lies outside himself, which he apprehends as some kind of intuitively sensed first principle. The unattainability of that becoming one, the inadequacy of his own ‘I’, is the perpetual source of man’s dissatisfaction and pain.

And so art, like science, is a means of assimilating the world, an instrument for knowing it in the course of man’s journey towards what is called ‘absolute truth’ …

Art is born and takes hold wherever there is a timeless and insatiable longing for the spiritual, for the ideal: that longing which draws people to art. Modern art has taken a wrong turn in abandoning the search for the meaning of existence in order to affirm the value of the individual for its own sake.

What purports to be art begins to look like an eccentric occupation for suspect characters who maintain that any personalized action is of intrinsic value simply as a display of self-will. But in artistic creation the personality does not assert itself, it serves another, higher and communal idea. The artist is always a servant, and is perpetually trying to pay for the gift that has been given to him as if by a miracle.

—Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time: Reflections on the Cinema

Photograph: Mosfilm

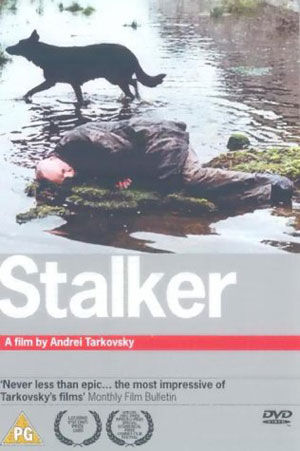

Stalker

My first taste of Tarkovsky’s genius on film was Stalker (1979), loosely based on the novel, Roadside Picnic, by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, who also wrote the screenplay.

On the surface, the plot is fairly straightforward: a meteorite has decimated a provincial Russian town twenty years previously, the area of which is now dubbed “The Zone”, having been mysteriously infused with supernatural power. There is an inner chamber within The Zone called “The Room”, which once entered will fulfil your deepest desire. The Zone is fiercely guarded by the local army; however, the desperate and suffering make the journey to The Zone, despite the fact that many have disappeared in their attempts.

A successful Writer (looking for inspiration?) and a Scientist (looking for scientific explanations?) enlist the help of an experienced Stalker, or guide, to help them reach The Room, in order to realize their innermost dreams. Despite their arduous and dangerous journey, upon the threshold of entering The Room, they both falter, crippled with feelings of remorse and self-doubt. As Oscar Wilde once said:

There are only two tragedies in life: one is not getting what one wants, and the other is getting it.

And so it is with the Writer and Professor; such is their anxiety over the potential manifestation of their most secret inclinations, it leads them to a spiritual crisis and to question the very nature of their lives.

Interestingly, throughout the entire length of their journey, it is Stalker who is forever wrestling with his spiritual conscience, never even wanting to venture into The Room. In a poignantly solitary moment, he laments the state of his own existence, one in which he no longer has any desire for anything, other than helping others access The Zone. This state of desirelessness, however, brings him no peace.

Photograph: Mosfilm

At this crucial turning point of the film, Stalker recites a poem, written by Tarkovsky’s father, Arseny Tarkovsky, considered to be one of the great twentieth-century Russian poets, and which was added to the screenplay:

Now summer is gone

And might never have been.

In the sunshine it’s warm.

But there has to be more.

It all came to pass,

All fell into my hands

Like a five-petalled leaf,

But there has to be more.

Nothing evil was lost,

Nothing good was in vain,

All ablaze with clear light

But there has to be more.

Life gathered me up

Safe under its wing,

My luck always held,

But there has to be more.

Not a leaf was burnt up

Not a twig ever snapped…

Clean as glass is the day,

But there has to be more.

And what is “more”? Stalker can all but hope for an omnipotent power, which surpasses even that manifesting inside The Room.

Photograph: Mosfilm

Beauty is summoning

Back at the café from whence they all originally departed, the arrival of Stalker’s wife confounds the Writer and Scientist, for here is a woman who has suffered interminably for her husband, bearing him a disabled child, and yet still she continues to love him with the same selfless devotion of her youth.

It is her unconditional love and human dignity that triumph in a world polluted by greed, secularism and self-interest, a world in which the Writer and the Scientist are both victims and fall foul.

Tarkovsky again:

I see it as my duty to stimulate reflection on what is essentially human and eternal in each individual soul, and which all too often a person will pass by, even though his fate lies in his hands. He is too busy chasing after phantoms and bowing down to idols.

In the end everything can be reduced to the one simple element, which is all a person can count upon in his existence: the capacity to love. That element can grow within the soul to become the supreme factor, which determines the meaning of a person’s life. My function is to make whoever sees my films aware of his need to love and to give his love, and aware that beauty is summoning him.

Photograph: Mosfilm

I have to say, watching Stalker has made all the films I have seen in the past pale into complete insignificance. I cannot think of any director who manages to encompass such a profound spiritual vision into his work, where in fact the spiritual vision IS his work. Interestingly, it is said that when Tarkovsky moved to the West, he read the complete works of George Ivanovich Gurdjieff, which greatly influenced his cinematic art.

The film is beautifully shot, with chromatic shifts in monochrome, sepia and colour, symbolic of the geographical locations in the film, as well as the states of mind of the characters. The haunting soundtrack comprising electronic synthesizers, tar and flute, composed by Eduard Artemyev, adds a further brooding, psychedelic element to the overall aesthetic experience.

In the final scene, Monkey, the daughter, sits quietly at a table, surrounded by glasses. In an utterly mesmerizing sequence, by an act of telekinesis, she moves the glasses along the table, one of which falls off and rolls away. A train then passes by, rattling the entire house in its wake. What does it mean? Individual divinity? Faith triumphing over suffering? Who knows. But it is a fitting end to an exquisite film.

Post Notes

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Instant Light

- Nostalghia.com: an Andrei Tarkovsky information site

- Open Culture: free Tarkovsky films online

- Arseny Tarkovsky: Life, Life

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Sergei Parajanov: The Colour of Pomegranates

- Ben Rivers: Two Years at Sea

- Carlos Reygadas: Japón

- Carl Theodor Dreyer: Ordet

- Abbas Kiarostami: 24 Frames

- Kaneto Shindo: The Naked Island

- Lisandro Alonso: Jauja