Image: Public Domain

How the solitary life by the sea

gave one woman a reason to live

I open my eyes in a darkened room. Am I alive? Logos moves as I rear up on the bed to turn on the light. Two o’clock. Shielding my eyes, I see that I’m fully dressed. I wash my face and brush my teeth. I didn’t eat last night. Is it worth feeding this body? I make some hot cocoa, and find a bowl of tuna salad in the refrigerator. My first meal on Christmas Day, 1962. Or my last, ever.

I’ve crossed a bridge unlike any other. I’m no longer among the living but among those who are about to die. From this side I can look back at what it was to be alive. All those people whose approval I sought: none of them is here now. The half dozen people I’ve thought of as my friends: not here either. I’m looking my own death in the face, and there’s no one to stand here with me. Alone, dying, as I was alone living.

From this side, how can it matter what anyone else thinks? From this side, how can it matter what I look like? From this side, how can anything at all matter? Is now the time, then? Is it?

AN UNKNOWN WOMAN by Alice Koller (13th September 1925–21st July 2020) is one of those rare and timeless books that improves with repeated rereading. Written in straightforward, even stark prose, it contains, nonetheless, profound insights into the psychological and philosophical issues of self-identity and what it means to survive in a world that no longer makes any kind of sense.

Having reached an existential crisis at the end of her thirties, Alice Koller decides to remove herself, quite literally, from the workaday world and the tedium of the daily grind. Despite having a PhD in Philosophy from Harvard University, she has spent many years working as a jobbing clerk and typist, flitting from one city to the next, her only aim to earn enough money to keep body and soul together.

More specifically, her quest to find the “perfect relationship” with a man has left her disillusioned with humanity and its vain hopes and empty promises of ever finding a worthwhile and meaningful life.

Image: Public Domain

The October morning sunlight pours against my reflection in the bathroom mirror in a New York apartment that isn’t mine. My makeup has ceased to be a subterfuge: it looks thick and caked, even though I carefully rub off all but the barest cover for my skin. Two long lines are being etched on either side of my mouth. Semicircles are beginning to form under my eyes. My thirty-seven years haven’t been visible until now. I can no longer conceal them […]

I stare into the mirror. I don’t have a life: I’m just using up a number of days somehow. There is no reason for me to be here. No plan formulated at some point in the past has led me to this void that is my day, every day. No obligation requires me to live in this apartment, or in this city. I don’t live anywhere: I perch. Four months in New York, three in Cambridge … Two months in Berkeley, four in Santa Barbara. Boston. New York again. I despise my busy-work job, and yet I don’t try to find something else. I try, instead, to turn it into a permanent connection: I must be certain of my income, at least. I must have something certain in all this flux: no career, no home, no man […]

I’m tired, from the inside out. Tired of perpetually having to fight for everything: degree, men, jobs, money. Tired of running after things that always elude me […] It has to stop. Can’t I just stop, right now, and try to figure out what I’m doing. What I should be doing?

If I could only get away somewhere. Somewhere quiet, without traffic or factories. Somewhere I can be really alone, so that I don’t have to be pleasant to people all day long, so that I don’t even have to see other faces when I walk outside my door. Somewhere where I don’t have to do anything but think all day long […]

I sit down on the edge of the tub, trembling. I have a goal that is my own. A goal: a focus for the long minutes of the day. I will get money, and then I will go away.

Finding an ad in the weekend newspaper for a “totally private but not isolated” house in Siasconset, on Nantucket (of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick), an island off the coast of Massachusetts, she wastes no time in extricating herself from her current existence.

She also decides to procure a dog, a male German Shepherd, “To warn me about strangers. To take walks with me. Yes, that makes it all fit together.” But there’s just one problem—what shall be his name?

This puppy will be my only contact with anything living. He’s the only creature I’ll be talking to. Words. Discourse.

Logos. I say ‘Logos’ over and over. This is the name. Logos: the rational principle of the universe; the Word; reasoned discourse. The puppy’s name is Logos.

Image: Public Domain

In the manner of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden, Koller immerses herself in the simple, solitary life in order to cleanse the dross of her troubled past and reveal her deepest, innermost self. After stocking up on provisions, housetraining her puppy and acclimatizing herself to the rhythms of Nantucket, she finally turns to address the serious business in hand:

Now I have to begin. I sit in front of my typewriter, aware of this moment as the center around which all of my preparations have swirled. I’m here to understand myself, deliberately to turn myself open to my view. I know, as I sit here, what I must have known for many years: that I can recognize what’s true about myself when I see it. It’s whatever I find myself refusing to admit, whatever I say no to very fast. That blanket admission right at the start may save me a lot of time. May save me, period. I’m using that ‘no’ to protect myself from something. What? I’ll find out. I’ll write down everything I can remember, so that I can see the full extent of it, pick out some patterns in what I’ve been denying for so long.

So that’s first: to get it all written, no matter how ugly.

But I know now, too, that all the years I made myself sit over philosophy books, examine philosophers’ reasoning, set out my own reasoning for a teacher to examine—all that accumulated discipline can now be shaped into the one tool I need: to be able to say with perfect care whatever I want to say. I can push my saying to the point of saying what I mean.

Acting as her own psychotherapist, Koller embarks on a retrospective dissection of her outer and inner life—friendships; relationships with parents; career choices as a professional actress and academic; liaisons with the opposite sex. Nothing is exempt from her discerning scrutiny as she endeavours to find the very source of her pain and unhappiness.

She quickly develops a daily routine of writing, collecting her mail from the post office, walking with Logos along the beach. Without, her existence is basic and uncomplicated and yet a maelstrom of emotion and feelings are roaring within:

I walk: desk to couch, couch to table, table to fireside chair, chair to stove, stove to refrigerator, and there I lean, crying … Why am I here? There’s no place else to be. What am I doing here? I don’t really know. What am I trying to do here? To find some way to live […]

Damn it, damn it, damn it. I make a hard fist with my right hand and punch the side of the refrigerator until the fleshy edge of my hand hurts. I make a pillow of my arms and lean up against the cold smoothness, burying my head. I can’t do it. I can’t think my way through thirty-seven years of not knowing what the hell I’m doing. What a fake, a fraud, a phony, an ignorant bitch I am. I sit here on an island with a typewriter and some paper, expecting the truth to unfold before my waiting eyes. I’m playing a part: another role for the big actress. Footlights up. Houselights down. Curtain. Scene: the hermit in her retreat.

Image: Public Domain

As the weeks pass by, the quietude enables Koller to delve deep within her past and isolate the source of her insecurities and suffering. By examining the relationship—or lack of—with her mother, she realizes that all her disastrous encounters with men and her ill-fated acting career stem from the primordial need to give and receive love:

Suddenly […] ideas crash together inside my head. The applause I played for everywhere and the attention I made my mother give me were exactly the same thing: substitutes for her love. I tried to make the whole rest of the world give me what she couldn’t give me. If I were the greatest actress, maybe she’d look at me. And if she looked at me, I’d have her attention, her real attention, which was her affection: I’d have her love. So of course I could never get enough attention from other people, because they were always giving me the wrong thing: they weren’t giving me her love. I’ve never believed that I’m beautiful because she never told me that I was.

I lay my forehead hard against the desk, and my arms encircle my head. I have to realize that my thirty-year trail away from being a little girl has been nothing more than standing on the same spot, moving my legs up and down. I’ve never stopped being that five-year-old, old enough to know that I was missing something, not old enough to know that it surely ought to have come to me without my having to pay for it. And I’ve been trying to buy it, lying and pretending ever since.

So. All the years are wasted. I’ve been doing things for a reason irrelevant to the doing of them. How could I have known what I want? I’ve skimmed over the surface of things, hoping to extract from them something they couldn’t possibly contain.

But Koller doesn’t stop there. Courageously, she continues to deconstruct the framework of her personality until she reaches the very foundation of her egoic self:

Oh, creature, who is this ‘I’ that I speak of? The only ‘I’ there is is a little girl, kept a dwarf for thirty years by a need that has only to be said out loud to be discarded. I grew up all around it, festering around a core that I didn’t know existed. To remove the core is to remove the whole growth that it supported. I’m now cut back to the bare ground […]

How can I think of going to New York to look for a teaching job? It’s all I can do to find reasons to eat, to dress, to get out of bed. I can’t imagine what reasons could get me on a plane, could let me ask a lot of people who have never helped me before to help me now. To help me do what? Find a job that will give me money to keep me fed and dressed. But that’s not enough to get me out of bed each day. First I have to find a reason for doing that […]

I haven’t really lived this life that’s lasted thirty-seven years. I’ve only played at living it, pretending I’ve been alive, saying and doing things to let other people believe I’m alive. But the joke’s on me. Because now that I’ve stopped playing the game, there isn’t anything real to take its place. I’m not even capable of recognizing what I’d be looking at if I were to come upon something that wasn’t a game.

Image: Public Domain

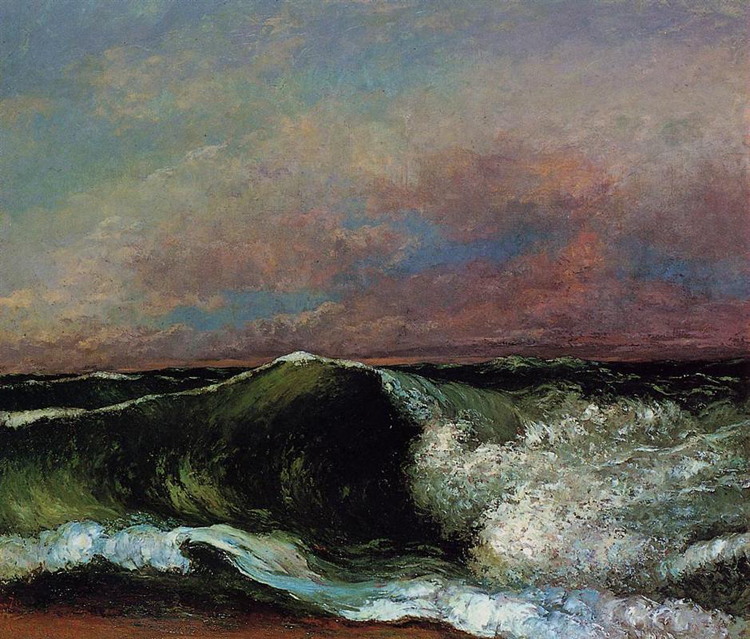

Amidst all the Sturm und Drang of Koller’s interior world, it is the sea that forms an omnipresent counterpoint, a tranquillizing and yet masterful being, in which all her anxieties and qualms are washed away by the spume and foam:

Being three steps away from my first look at the water each day is as exciting as though I were about to meet a man. The difference is that here I am never disappointed. The sea is always there and glorious, no matter what the wind or sun or lack of either does to it. It always catches me up into itself. From this point on the bluff, where my eye takes in the shore with the expanse of water toward the horizon, the very familiarity of the view enlarges my sense of its beauty. My walk begins with this smile.

Moreover, the vast oceanic expanse acts as Koller’s father confessor, a nonjudgmental, silent witness to her sacramental confession and absolution:

I study the curving line of the shore, the separation of sand and water cleanly marked by the narrow white edge of low tide. There is very little wind, the day is brilliant, the horizon seems within reach. It is fantastically beautiful here.

I shake my head to make the pieces of my interior kaleidoscope slide from pattern to pattern.

I’ve accomplished nothing in two different attempts at a career. No relationships I’ve ever had with a man were genuine. I missed out on being equipped with the most basic tools for living life: purposes and wantings and feelings are beyond my comprehension. Can I think of my life as valuable to me, even though it doesn’t matter to anyone else?

Valuable. I visualize the word. It carries no meaning for me.

Wait. It’s true that I’ve accomplished nothing in the eyes of people that I’ve let judge me. But suppose I use my own eyes. Suppose I take myself as my judge. That doesn’t transform my failure into accomplishment, but it lets me see what the failure was: I failed because the things I set myself to do weren’t things I chose to do. There was no real ‘I’ to do the choosing. That hollow creature led by a child’s heart, fighting rearguard actions all over the place to prevent anyone from noticing: I’ve torn it all away. And look what’s left: this small shuddering self.

Image: Public Domain

It is Christmas Eve, 1962. Koller’s philosophical journey has reached its emotional climax. As the dark night of the soul descends upon her, a lone inner voice surrenders to the inevitable void:

‘No!’ I get down on my knees and spike the floor. ‘No. No. No. No. I can’t stand it anymore!’ I lay my head on the cushion of the chair next to the fireplace, and bring my arms up to cradle my head, to close my ears off from what I am saying, to shut my eyes against what I see: Christmas Eves to come, a thirty-year, forty-year chain of them, empty, like this one. Not a chain of unconnected Christmas Eves, but an endless chain of days. Christmas Eves are only one day in each group of 365 empty days. Not only Christmas Eve, but all the other days, too, will be like this day […]

So I’ve reached a neutral point: it makes no difference whether I live or die. I’m afraid of nothing that lies ahead of me, and I leave nothing behind me. No more counting pennies, asking someone to put me up until I get money, waiting for some man, wondering whether I’m smart or beautiful. No more asking anyone for anything at all.

I sit down on the couch, head back, hands clasped loosely on my lap. To have thought myself so big; to have found myself so small. To be nothing: to be qualified to do nothing, to be capable of doing nothing, to be needed for doing nothing, to want to do nothing.

While the rest of the world celebrates the Yuletide festivities, Koller wonders whether, in the midst of a sea of nothingness, she has even any will left to live. It is now 26th December:

I am awake one day beyond my time. Have I decided to live? I think I have only not decided not to. If I live, my life will have to be all mine, not anyone else’s. No one else saved it, if saving it is what I’m doing, and no one else can take its measurement. I haven’t very much to go on, but I’ll find my own way by myself, not by anyone else’s version of what I can or cannot do. I don’t know yet what I want to do, but when I find it out, I’ll do it. Whether I’ll do it well, whether I have the talent for it: these questions won’t arise. ‘Is this the thing I want to do?’ There’s the point on which my pressure won’t relent.

In the meantime, there are these days from waking to sleeping. Each one of them makes up my life. Each one of them must give me the same sense of whatever-it-is that being with Logos gives me, that walking along the ocean gives me. Closeness. Fitting me. Belonging.

Yes, from now on, I’ll shape my day to make each thing in it fill me.

I shall measure everything I do against my knowledge that I can die. Not just that I’m flesh and shall therefore one day die, but that I, by my own hand, can choose the day. Of each thing that I do, I shall now ask, ‘Is this thing I’m doing worth being alive for?’ The very doing is what matters. Even when I choose some future good toward which these present minutes point, I won’t let there be hours that I only tolerate. I won’t ever put up with unthinking habit or being bored, or ugliness in things or persons. I have nothing important to do, but I have no time to waste marking time. Each thing I touch or see or smell or taste or hear during my day must give me the sense of something good in the doing.

Image: Public Domain

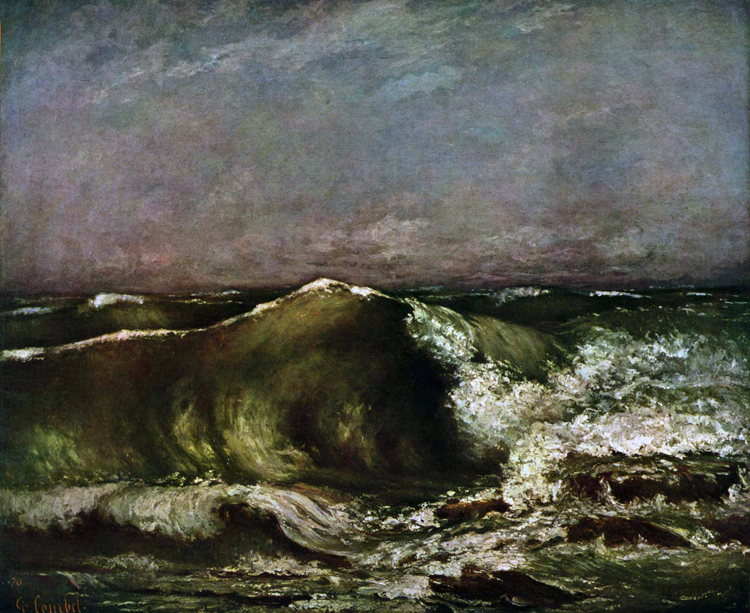

As the storm clouds abate, Koller feels the swelling of a deep peace and inner harmony. All the mental jetsam has drifted away, with only the most important salvage remaining from her life:

I am disburdened. That’s it. Free: not obliged, not required, not compelled to do anything. Free: no longer condemned to keep repeating the disasters of the past […]

And I know some few things. I love Logos: I must have him with me. I can’t think of myself without him. This ocean matters to me: my free access to it, the silence and the beauty, the vastness of the view.

Suppose I start with these things. And with the idea that other things may join with these. I don’t know now what they’ll be. Or when they’ll come to me. Or whether there will be anything else at all.

But I start with these. They are all the self I have. But they are mine.

A memory then floats to the surface of her mind of a young woman, who left an indelible impression, which only now can she fully appreciate:

The nun who stopped me on the Berkeley campus last year. Her black robes being blown by the wind entered into my peripheral vision as I lay reading on the sloping ground […] As she climbed the winding path, I realized that it was her own movement, not the wind, that were making her robes whip and flow around her. She was walking, not mincing. Her stride was long but graceful. It was the walk of Indians.

I turned back to my book, but then I heard footsteps on the grass behind me and there she stood, looking down at me, her hands clasped loosely in one more easy gesture. [Alice Koller then directs her to the information office.]

She smiled at me again, thanked me, raised her hand a little higher than the gesture that had told me not to disturb myself, and said, ‘God bless you.’ She spoke directly to me, as though she were imprinting the words on my mind. And then, in the same astonishing harmony, her body moving without hindrance, moving with its garments rather than in opposition to them, she started up the hill again.

I stood looking after her until she was out of sight. She was the only person I had ever seen who was free. She moved so naturally because inside she was also graced. When she blessed me, I understood that she was giving me something of what constituted the core of her being. It was something that was at once so personal and yet so impersonal that I almost ran after her to ask her to explain to me how that could be […]

I know why I think of her now. Things have been feeling new to me for the past several days, and she, in spite of her acquiescence to the authority her robes symbolized, remains in my memory as some exemplar of independence. No, not quite. Of genuineness: although she accepted the authority of the Church, it was she who chose it, and her choice freed her. How do I know? It was the quality that came across to me.

Image: Public Domain

Again, the uncompromising simplicity of Koller’s narrative acts as a foil to the perspicaciousness of her mind. Moreover, the absence of any quotations taken from illustrious philosophers of the past gives her autobiography an accessibility and immediacy one wouldn’t expect from someone with such a formidable academic career.

Even her own opinions, in the company of others at least, no longer interest her:

Talking about myself was my way of inviting people to think about my problems; to help me solve them; to (Jesus!) feel sorry for me because the knots were so entangled; to reassure me; to compliment me. Oh, most especially that: to tell me how clever and bright and kind and beautiful and insightful I was […]

I don’t need to talk about myself any longer because I don’t need people for those purposes any longer. I certainly don’t need people for solving my problems: I fall into thinking about them without constraint; I find myself handling them in some way that ends up being comfortable, suited to me. I can even tolerate not resolving them immediately. I can let them go back to be chewed over a little longer […]

And I don’t need anyone to tell me what I’m like, what I do well, what I ought to try. I know who I am a little bit more each day. I simply am this or that, so compliments and reassurances are both irrelevant. It’s a waste of both our time for me to invite anyone else to evaluate me: no one else can have my vantage point on me.

Image: Public Domain

Rarely have I been so captivated by such a raw and honest confession of someone’s interior world. Indeed, the non-sectarian, unpretentious vocabulary serves only to reinforce the profundity of her unique and remarkable journey, one which transcends language and even knowledge itself:

What sort of knowledge is this, that it can’t be taught either by specific example or by abstract precepts? I think it’s that knowledge Socrates meant when he said that virtue is knowledge but it can’t be taught. It can’t be taught but it can be learned. You have only to set yourself to be both teacher and learner at the same time. What you learn is something true of yourself alone. The reason no one else can teach it to you is that anyone else who has such knowledge knows only something which is true of himself, of herself, alone, too. Should it be called ‘knowledge’ at all, since it concerns what is unique, as every self is?

The New Year rolls in and it is time for Koller and her “Sweet Puppy” to depart. In the final chapters, after having found the elixir of existence, her preparations for leaving are anticlimactical, even banal—packing up her books into boxes; buying a new collar for Logos; washing the rug on the living room floor. Life has a brand new flavour and yet its implications are taking time to fully assimilate.

In fact, she does not yet know what sort of life will befall her beyond her solitary sanctuary. For now, at least, there will be no more pining for intimacy with others, no more searching for completeness outside herself. Man, or indeed woman, may not be an island, but for Alice Koller, her reclusion on Nantucket will remain forever in her heart:

I stand watching the whitecaps form and roll into shore.

I don’t have to wait to get married to have a home: I’ll make my own […] I don’t have to wait for someone to give me a sense of continuity: I’ll carry my continuity within myself. I’ll belong wherever I am. I’ll institute my own permanence.

I find myself smiling.

Post Notes

- Virginia Woolf: A Room of One’s Own

- Michel de Montaigne: On Solitude

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Meditations of a Solitary Walker

- Philip Gröning: Into Great Silence

- Xavier Beauvois: Of Gods and Men

- Shūsaku Endō: Silence

- Ajahn Sumedho: The Sound of Silence

- Rainer Maria Rilke: On Solitude

- John Zerzan: Silence

- Alexandra David-Néel: My Journey to Lhasa