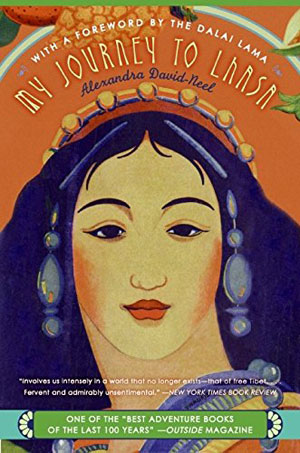

Image: Public Domain

How a woman’s quest for solitude

led her to Tibet’s forbidden city

“How happy I was to be there, en route for the mystery of these unexplored heights,

alone in the great silence, tasting the sweets of solitude and tranquillity.”

ALEXANDRA DAVID-NÉEL’S travelogue belongs to an era when it was possible to slip into protracted obscurity and follow one’s dreams to the very end of the earth. Such was its impact, My Journey to Lhasa influenced many of the Beat writers, including Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, as well as the Eastern philosopher, Alan Watts.

And thus in 1923, intrepid and unperturbed, a fifty-five-year-old French woman, a former opera singer and one-time director of the Tunis Casino, set off disguised as a male pilgrim with her adopted son Yongden, a “Red Cap” lama, to ascend to the ancient Tibetan city of Lhasa, becoming the first European woman ever to try in the attempt.

Ever since I was five years old, a tiny precocious child of Paris, I wished to move out of the narrow limits in which, like all children of my age, I was then kept. I craved to go beyond the garden gate, to follow the road that passed it by and to set out for the Unknown …

Image: Preus Museum,

[CC BY 2.0] Wikimedia Commons

At the time of her journey, Tibet was under the control of an autonomous government based in Lhasa, having recently gained independence from China; in order to prevent any outside influence, all foreigners were prohibited from travelling throughout the country. Inspired by the challenge, David-Néel’s beautifully written narrative is thus all the more compelling when the possibility of exposure from her incognito status is always hovering just under the text.

Entering the path

Alexandra David-Néel (24th October 1868–8th September 1969) was already a veteran spiritual mendicant, having studied Oriental philosophy and comparative religion in Paris, as well as having travelled for many years living in monasteries and caves throughout Asia and the Far East. She was also proficient in both Tibetan and Sanskrit and had been ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist nun.

Entering from China, mother and son pose as arjopas, or religious pilgrims, begging for food and shelter as they follow the Mekong River towards the Dokar Pass, carrying very few possessions lest David-Néel’s identity be discovered, with the exception of a pistol, a compass and a couple of old spoons.

Image: Public Domain

Being winter time and often travelling at night to avoid detection, their journey is treacherous and exhausting. Bands of thieves roam the gorges and valleys, preying on wandering mendicants, only serving to add to the dramatic suspense. The region is also densely forested and mountainous, forcing them to navigate their passage, often through snow and ice without the aid of maps, relying only on the dubious directions of local natives.

No return

Despite bodily privation and extreme physical hardship—not least when Yongden injures an ankle leaving them both stranded for several days without food in the midst of a whiteout—David-Néel remains steadfast in her commitment to reaching the forbidden city, even taking time to admire the stunning surroundings along the way:

… the scenery was grand beyond all description. Behind extended the waste I had crossed. In front of me was a precipitous fall of the mountain. Stretching far below, black undulating crests vanished into the darkness. The moon rose as I looked around in a trance of admiration. Its rays touched the glaciers and high snow-robed peaks, the whole white plain, and silvery unknown valleys toward which I was to proceed.

The impassive landscape of the day seemed to awaken under the blue light which metamorphosed it, sparks glittered to and fro, and faint sounds were wafted by the wind …

Image: Public Domain

Maybe elves of the frozen waterfalls, fairies of the snow and djin-keepers of mysterious caves were to assemble and play and feast on the illuminated white tableland; or perhaps some grave council was to take place between the giants whose heads wore helmets of cold radiance.

What mysteries could not have been discovered by the inquisitive pilgrim who, hidden, dared remain there motionless till dawn. Not that he could ever have related the wonder of the bewitching night, for his tongue would soon have been stiffened by frost!

Mother and son confront every challenge presented to them on their arduous journey: the persistent demands by local villagers to tell their fortunes and exorcize demons; an attack by bandits forcing David-Néel to fire off her revolver; a ghostly lama’s fireside visit in the dead of night.

Even when the odds are stacked against them, David-Néel is always resourceful. Utterly fatigued by many long hours of tramping, she is desperate to light a fire to make buttered tea and generate warmth, using an esoteric breathing technique, which involves going into a trancelike state in order to raise the internal temperature of the body:

… the flint and steel were wet and cold. What if I warmed them on me, as I had dried dripping sheets when a student of thumo reskiang [tummo]? Thumo reskiang is but a way devised by the Thibetan [sic] hermits of enabling themselves to live without endangering their health on the high hills …

I put the flint and steel and a touch of moss under my clothes, sat down, and began the ritualistic practice. I mentioned that I felt sleepy on the road; the exertion while collecting fuel and pitching the tent, the effort to kindle the fire, had shaken my torpor, but now being seated, I began to doze. Yet my mind continued to be concentrated on the object of the thumo rite. Soon I saw flames arising around me; they grew higher and higher; they enveloped me, curling their tongues above my head. I felt deliciously comfortable.

Image: Public Domain

A loud report awakened me. The ice on the river was rending. The flames suddenly died down as if entering the ground. I opened my eyes. The wind was blowing hard and my body burned. I made haste. The flint and steel and moss would work this time; I was convinced of it. I was still half dreaming, although I had got up and walked toward the tent. I felt fire bursting out of my head, of my fingers.

I placed on the ground a little dry grass, a small piece of very dry cow dung, and I knocked the stone. A spark sprang out of it. I knocked again; another sprang out … another … another … a miniature fireworks … The fire was lighted; it was a little baby flame which wanted to grow, to eat, to live. I fed it and it leaped higher and higher. When Yongden arrived with a quantity of dry cow dung in the lap of his dress and some branches between his arms, he was joyfully astonished.

Final fruit

At last, their travails are nearly over; they are only a few miles from the forbidden city and already they are able to see the Potala, palace of the Dalai Lama, rising up before them in the distance:

As we advanced, the Potala grew larger and larger. Now we could discern the elegant outlines of its many golden roofs. They glittered in the blue sky, sparks seeming to spring from their sharp upturned corners, as if the whole castle, the glory of Thibet [sic], had been crowned with flames. Our eyes fastened upon it. We walked with a good speed, for success was near and gave us wings.

They find humble lodgings and during their two-month stay, mingle unnoticed amidst the New Year festivities and ceremonies, temples and hovels, markets and city streets. David-Néel has accomplished her dream and is fulfilled with overwhelming tranquillity. Only when they leave for Bhutan does she finally renounce her beggarly disguise and assume the role of a middle-class woman in preparation for the long journey back home to the West.

Despite being highly pragmatic and rational, often dismissing the superstitious beliefs of the local Tibetans as utter nonsense, Alexandra David-Néel is also deeply affected by the mystical phenomena she encounters, believing that their journey is blessed with a divine hand.

Image: Public Domain

Indeed, before their departure from the forbidden city, she stocks up on a selection of Buddhist books to help with her studies on Eastern philosophy, something which she continued steadfastly to do right through to her death at one hundred years old, when her ashes and those of Yongden who had died a number of years before her, were thrown together into the Ganges.

In order that you may awaken to the supreme deliverance, free yourself from fear and grief, turn your steps toward Knowledge … Just as, in the sky, the clouds form and melt away, without our knowing whence they come or whither they go, and without there being anywhere a dwelling place for the clouds, so do phenomena appear through a combination of causes and vanish through the operation of other causes, without our being able to assign any of them a place where they may dwell …

Post Notes

- Alexandra David-Néel’s official website

- Central Tibet Administration

- Irina Tweedie: The Daughter of Fire

- Hildegard of Bingen: Sibyl of the Rhine

- Alice Koller: An Unknown Woman

- Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love

- Mahapajapati Gotami: Mother of All

- Hermann Hesse: The Journey to the East

- Ismaël Ferroukhi: Le Grand Voyage

- René Daumal: Mount Analogue