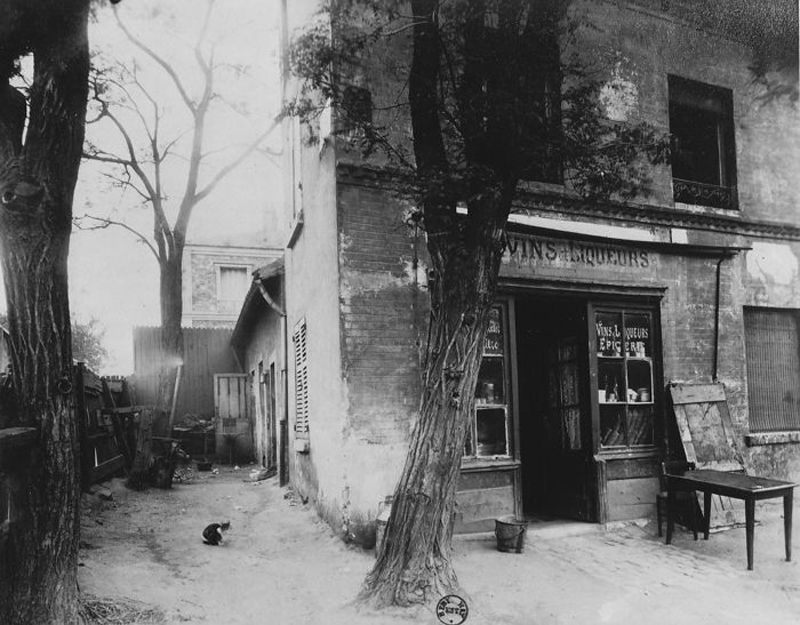

Image: Public Domain

Choosing to live

“Jetez-moi dans la mer …

car je sais que c’est moi qui attire sur vous

cette grande tempête.”

“Cast me into the sea …

For I know that for my sake

This great tempest is upon you.”

—Jonah 1.12

THE FRENCH PHILOSOPHER, Blaise Pascal, famously stated in his Pensées, « Toutes les difficultés de l’homme viennent de son incapacité à s’asseoir tranquillement dans une pièce en sa seule compagnie. » (“All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.”) Indeed, the themes of silence and solitude have both fascinated and frustrated many eminent philosophers and artists alike, not least French-Algerian, Noble Prize-winning writer, Albert Camus (7th November 1913–4th January 1960).

Camus is associated with the Existentialist philosophers, who essentially surmised that life is absurd and devoid of meaning and, as such, the only metaphysical question we should ask ourselves is whether or not life is worth living. And yet, unlike his counterparts Søren Kierkegaard, Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre, who had more pessimistic worldviews, Camus believed not only must we nobly endure our suffering but that we should, in fact, celebrate our existence, specifically through championing ordinary life, be it through friendship, nature, food, sunshine, dancing, swimming, kissing, even football, which he revered above all else. As his famous essay, “Summer in Algiers” (“L’été à Alger”), concludes: “If there is a sin against life, it consists not so much in despairing as in hoping for another life and in eluding the implacable grandeur of this one.”

Image: Public Domain

Gilbert Jonas, artist and painter, believed in his star. Indeed, it was all he believed in, although he felt respect and even a kind of admiration for the religion of others. His own faith, however, had its virtues, since it consisted of admitting, somehow obscurely, that he had done nothing to merit what he had achieved. And when, around his thirty-fifth year, a dozen critics suddenly fought over the glory of discovering his talent, he showed not the slightest surprise. But his serenity attributed by some to smugness, could be on the contrary entirely explained by a trusting modesty. Jonas gave credit to his star rather than his merits.

—Albert Camus, Exile and the Kingdom, “Jonas or The Artist at Work”

Albert Camus is better known for his canonical novels, The Outsider (L’étranger), The Plague (La peste), The Fall (La chute) and the unfinished, The First Man (Le premier homme). It is his short story collection, Exile and the Kingdom (L’exil et le royaume), that particularly entrances me, however, including the magnificent “The Guest” (“L’hote”), recently dramatized into David Oelhoffen’s stunningly shot and impeccably acted film, Far from Men (Loin des hommes), which tells the tale of a reclusive, pacifist schoolmaster, Daru, who is tasked with delivering a murder suspect into the hands of the French authorities set against a backdrop of the Algerian War of Independence.

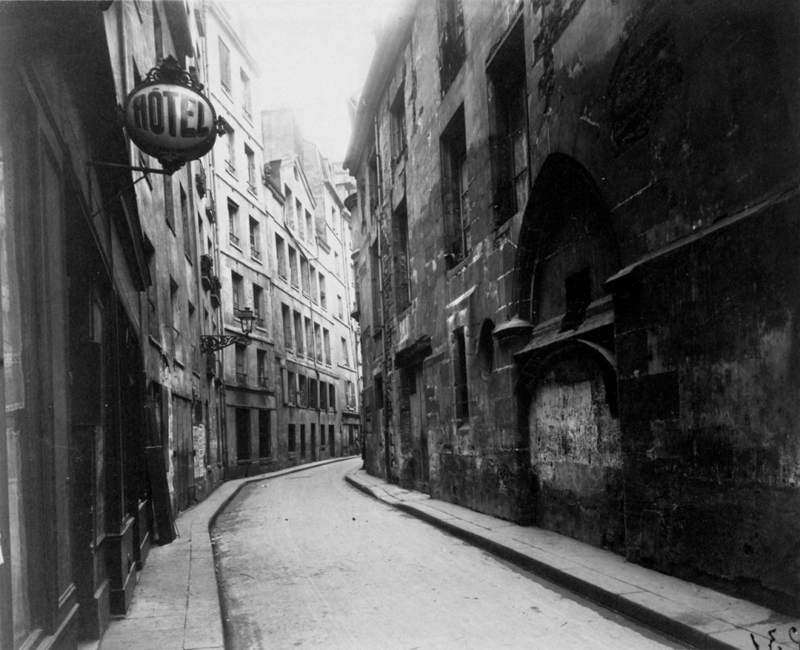

And yet whereas “The Guest” presents us with the themes of silence and solitude in the midst of a merciless land populated only by stones and the vagarities of the elements, “Jonas or The Artist at Work” (“Jonas ou l’artiste au travail”), also contained within the anthology, examines similar motifs amidst the domestic arrangements of an up-and-coming artist, situated in the very heart of an unnamed metropolis. Good-natured and forever the optimist, Jonas has found his true passion in life—painting—and lives a modest existence with his devoted wife, Louise, and their three children, supported by a monthly stipend, the brotherly friendship of his old school friend and architect, Rateau, and the guiding light of his star. Nevertheless, in spite of his benevolent surroundings, Jonas, akin to Daru, suffers an existential crisis, which forces him to re-evaluate the meaning he has given to life.

Image: Public Domain

Jonas was now attracting a school. At first, he had been surprised, not seeing what anyone could learn from him since he had still had everything to discover himself. The artist in him was groping in the dark; how could he teach the true paths? But he quickly understood that a disciple was not necessarily someone who aspired to learn something. More often, on the contrary, a person became a disciple for the disinterested pleasure of teaching his master. After that, Jonas could accept this surplus in honours with humility. The disciples explained to Jonas at length what he had painted and why. Jonas thus discovered in his work many intentions that rather surprised him and a host of things he had not put there. He thought he was poor and, thanks to his students, suddenly found he was rich. Sometimes, faced with such hitherto unknown riches, Jonas would feel a surge of pride. ‘It’s true, though,’ he would say to himself. ‘That face in the background really does stand out. I don’t honestly understand what they mean by indirect humanization. Yet I’ve gone rather far with that technique.’ But very soon he would shift this uncomfortable mastery to his star. ‘It’s the star,’ he would say to himself, ‘that’s going far. As for me, I’m staying close to Louise and the children.’

—Albert Camus, Exile and the Kingdom, “Jonas or The Artist at Work”

Jonas’ naïveté in the face of the manipulative sycophancy of his disciples and local art dealers is both touching and troubling as we witness his attempts to please everyone around him, inevitably at his own expense. Thankfully, his noble heart attributes his rising success to his star and he is able to retain his humble demeanour; nonetheless, the time and serenity he needs to create his paintings are severely impeded as his modest apartment fills up with the constant comings and goings of other people and their selfish needs.

Moreover, the challenge for any artist, not least a famous one, is made explicit in this elegant narrative that explores the way in which creative endeavour is often sacrificed for social pleasantries, economic necessity and familial ties—taking a stance against them risks rejection, alienation, even exile. Indeed Camus himself struggled throughout his life with being viewed as an outsider in metropolitan France, both ethnically (he was Algerian French, a so-called “pied-noir”, as well as being of Spanish descent) and intellectually (his non-acceptance of Left Bank Existentialism causing the acrimonious split with Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir).

Image: Public Domain

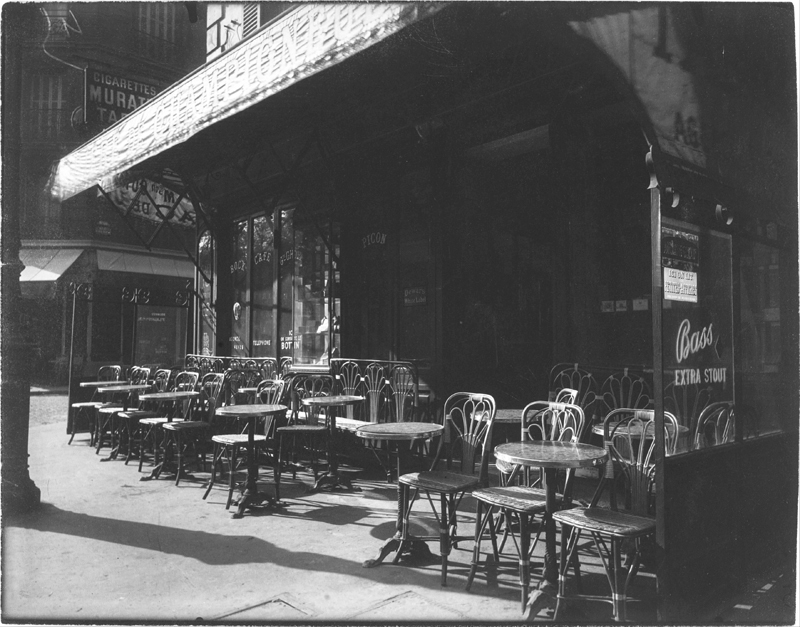

Yet Jonas was working less, without quite knowing why. He had always followed his routine but now he had difficulty painting, even in moments of solitude. He would spend these moments looking at the sky. He had always been distracted and absorbed but now he became a dreamer. He would think about painting, about his vocation, instead of painting. ‘I love to paint,’ he still said to himself and the hand holding the paintbrush would hang at his side as he listened to a distant radio …

On the days that followed he tried to work in the hall, the day after that in the shower room, under electric light, the next day in the kitchen. But for the first time, he was bothered by the people he encountered everywhere, those he hardly knew and his own family, whom he loved. He stopped working for a while and meditated. He would have painted a seasonal subject if the weather were better. Unfortunately, winter was about to begin, it would be difficult to do a landscape before spring. He tried, however, and gave up: the cold chilled him to the bone. He lived several days with his canvases, most often sitting beside them or standing motionless in front of the window. He was not painting anymore. Then he started going out in the morning. He would devise a project to sketch a detail, a tree, a crooked house, a profile glimpsed in passing. By the end of the day, he had done nothing. The slightest temptation—the newspapers, a chance meeting, the shop windows, the warmth of a cafe—held him spellbound. By evening he had no good excuse to assuage his lingering bad conscience. He was going to paint, that was certain and paint better, after this period of apparent emptiness. The work was going on inside, that’s all, the star would emerge again, washed clean and sparkling, from this dark fog. Meanwhile, he haunted the cafes. He had discovered that alcohol gave him the same exaltation as days of good work when he used to think of his painting with that tenderness and warmth he had never felt for anything but his children. With the second cognac, he rediscovered the poignant emotion that made him at once the world’s master and its servant. Simply he enjoyed it in a vacuum, his hands idle, without putting it into a work. Still, this was where he came closest to the joy he lived for and he now spent long hours sitting, dreaming, in smoke-filled, noisy places.

—Albert Camus, Exile and the Kingdom, “Jonas or The Artist at Work”

In a dazzling passage, Camus perfectly describes the ennui that beleaguered the intelligentsia of postwar Paris, harking back to his belief that despite the fact we are free, we are never quite free enough to escape. What exactly we cannot escape from thus becomes one of the most profound questions we need to ask ourselves, and yet for most, it is rarely addressed, let alone resolved. And so, like many of his artistic contemporaries, Jonas descends into listlessness and melancholy, interspersed only momentarily with fleeting moments of peace.

Interestingly, Camus dabbled in the writings of the Buddha and reputedly kept a wooden statuette of the ancient sage on his mantelpiece. Such oriental leanings undoubtedly infused his philosophical theories, which advocated living intensely in the here and now as a panacea to the transitoriness of existence and, more specifically, escaping from judgement and prejudice, thoughts and ideas, indeed the very nature of the restless mind itself. Reading Camus often reminds me of the American Beat writer, Jack Kerouac, another rebel and lifelong traveller, who similarly examined feelings of dissatisfaction, boredom and angst. Indeed, the two men bear uncanny resemblances in the way in which they experienced the world through their writings, being and interests—both wrote about the male rite of passage from disaffected youth to what it means to be human and a man; both were literary geniuses influenced by Buddhist doctrines and yet cut down at the peak of their careers; and both were devilishly handsome and had an enduring passion for the “beautiful game” of football.

Image: Public Domain

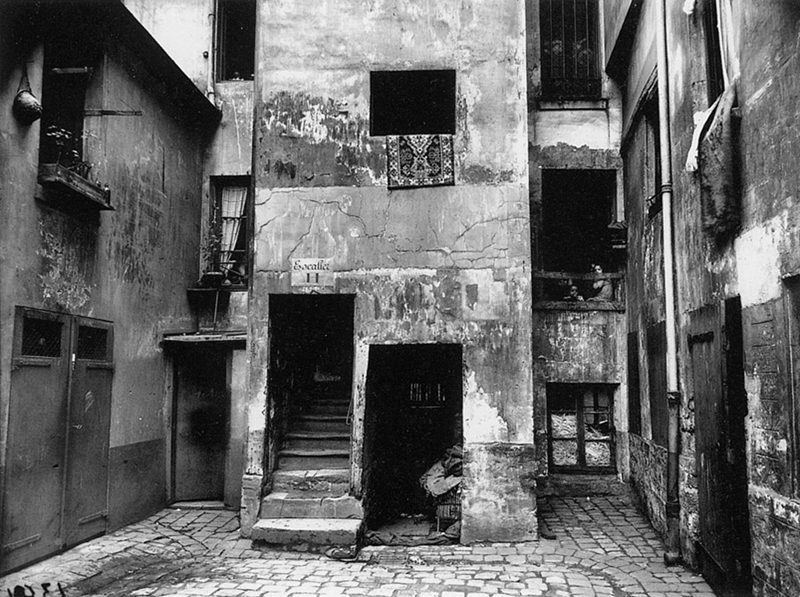

The next day, as early as possible, he climbed up to the loft, sat down, placed the frame on the stool against the wall and waited without lighting the lamp. The noises he heard were coming from the kitchen or the toilet. Other sounds seemed distant, and the visits, the ringing of the doorbell or the telephone, the comings and goings, the conversations reached him half-muffled as if they were coming from the street or from the other courtyard. Besides, when the apartment was flooded with a harsh light, the darkness here was restful. From time to time, a friend would come and camp beneath the loft. ‘What are you doing up there, Jonas?’—’I’m working.’—’Without light?’—’Yes, for the time being.’ He was not painting but he was meditating. In the darkness and this half-silence which, compared to his previous experience, seemed to him the silence of the desert or the grave, he was listening to his own heart. The sounds that reached the loft did not seem to concern him now, even if they were addressed to him. He was like those men who die at home alone in their sleep and when morning comes, the telephone rings and keeps ringing, urgent and insistent, in the deserted house, over a corpse forever deaf. But he was alive, he was listening to this silence within himself, he was waiting for his star, still hidden but ready to rise again, to emerge at last, unchanged above the disorder of these empty days. ‘Shine, shine,’ he would say. ‘Don’t deprive me of your light.’ It would shine again, he was sure of it. But he still needed more time to meditate, since at last, he had the chance to be alone without being separated from his family. He needed to discover what he had clearly understood, although he had always known it and had always painted as if he knew it. He had to grasp at long last that secret which was not merely the secret of art, he could see. That is why he did not light the lamp.

—Albert Camus, Exile and the Kingdom, “Jonas or The Artist at Work”

Interestingly, Camus wrote a two-act play or “mimodrama”, entitled “The Life of the Artist” (“La Vie d’Artiste”), prior to his short story, which unlike his other plays contains no dialogue, being constructed entirely of actions and stage directions. Written in a succinct, elliptical style, and oscillating between horror and humour, the drama again poses the perennial question—how can one be an honest, authentic artist and simultaneously live in a world replete with all the vacuous vicissitudes of the bourgeoisie? Composed during his faltering marriage and the fallout of his friendship with Sartre, coupled with the subsequent descent into a yearlong period of creative sterility and physical illness, the play ends tragically with the final curtain falling on Camus’ tragic hero whilst painting the face of his dead wife, his family and friends having long since abandoned him.

“The Artist at Work”, on the other hand, takes a very different stance. Despite suffering the same torment and inner conflict as his theatre double, Jonas personifies the reinvigorated Camus when he has had time to reflect upon his life and evoke a “metaphysical rebellion”. Perhaps Camus the iconoclast is even playing with the notion that, contrary to Sartre’s belief that existence precedes essence, existence is essence—akin to the Buddhist concept, samsara is nirvana—and that the two are, to all intents and purposes, one and the same. And so, in the darkened exile of his newly constructed mezzanine studio, Camus portrays the artist withdrawing his attention inward, falling into a deep and meditative silence whereupon he reconnects with the luminescent source of his being, his ever-patient and trusted star—the secret kingdom within.

Image: Public Domain

A beautiful day was dawning but Jonas did not notice. He had turned the canvas to the wall. Exhausted, he was waiting, sitting with his hands open on his knees. He told himself that now he would never work again, he was happy. He heard his children shouting, the water running, the dishes clinking. Louise was talking. The huge windows rattled as a truck passed on the boulevard. The world was still there, young, lovable: Jonas listened to the lovely murmur of humanity. From so far away it did not conflict with that joyful strength in him, his art, those thoughts that he could never express but that set him above all things, in an atmosphere that was free and alive. The children were running through the room, the little girl was laughing, and Louise, too—he hadn’t heard her laughter for a long time. He loved them! How he loved them! He put out the lamp and in the familiar darkness wasn’t that his star still shining? It was, he recognized it, his heart full of gratitude, and he was still gazing at it when he fell, noiselessly.

‘It’s nothing,’ the doctor who was called in declared sometime later. ‘He’s working too much. He’ll be on his feet in a week.’—’He will get well, you’re quite sure?’ said Louise, her face haggard.—’He will get well.’ In the other room, Rateau was looking at the canvas. It was entirely blank, though in the centre, Jonas had written in very small characters one word, which could be deciphered, but it was hard to tell whether it should be read as independent or interdependent.

—Albert Camus, Exile and the Kingdom, “Jonas or The Artist at Work”

Jonas’ falling from the entrails of the loft is deeply symbolic in that it represents his jettisoning of the final vestiges of his former self into a state of acceptance of his lot; more specifically, taken as a whole, “The Artist at Work” is about falling from societal grace and falling in love with life itself. Moreover, despite the fact that Camus was an atheist, his prefacing the narrative with words from the Biblical story of Jonah and the whale alerts us to his sardonic wit whilst simultaneously exploring the most profound of truths, namely reconciling the contradictory and complementary need for solitary reflection with communal engagement, the original French driving the point home through its enigmatic play on words: « Dans l’autre pièce, Rateau regardait la toile, entièrement blanche, au centre de laquelle Jonas avait seulement écrit, en très petits caractères, un mot qu’on pouvait déchiffrer, mais dont on ne savait s’il fallait y lire solitaire ou solidaire. »

In another of Camus’ seminal texts, The Myth of Sisyphus, he writes: “There are no more deserts. There are no more islands. Yet there is a need for them. In order to understand the world, one has to turn away from it on occasion; in order to serve men better, one has to hold them at a distance for a time. But where can one find the solitude necessary to vigour, the deep breath in which the mind collects itself and courage gauges its strength?” And therein lies the dilemma for all of us, particularly if we follow a creative path. As Camus so eloquently enlightens us in the short stories of his exquisite collection, temporarily shunning the world by immersing ourselves in the silence within, be it through hermetic confinement or simply a room of our own, we are able to reconnect with our inner star, in the manner of Daru and Jonas, reigniting our innate purpose for living and restoring our inborn passion for life.

Post Notes

- The Albert Camus Society

- Michel de Montaigne: On Solitude

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Meditations of a Solitary Walker

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Agnes Martin: Writings

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- Carl Gustav Jung: The Red Book, Liber Novus

- William Blake: All Religions Are One

- Josef Pieper: Only the Lover Sings

- Jack Kerouac: Alone on a Mountaintop

- Lisandro Alonso: Jauja

- Julian Schnabel: At Eternity’s Gate