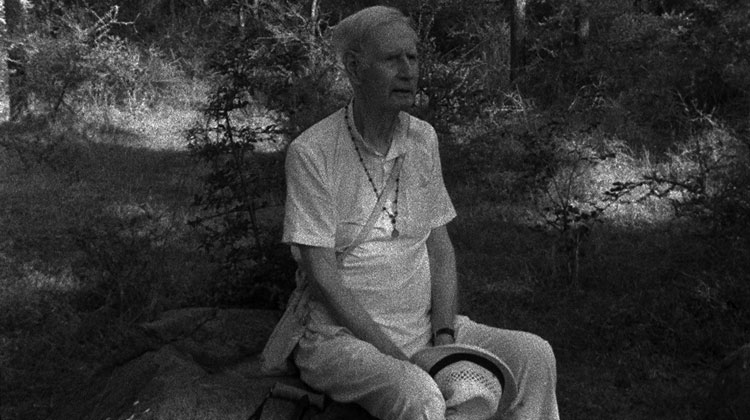

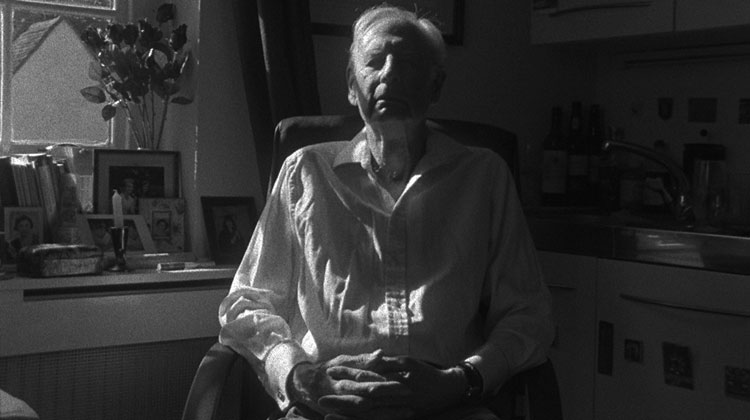

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 4.0] The Culturium

A dialogue on the nature of the Self

Alan Jacobs is currently President of the Ramana Maharshi Foundation, UK. In an interview with The Culturium’s Editor, Paula Marvelly, he discusses his spiritual journey, the teachings of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi and the answer to the most fundamental question of all, “Who am I?”

“Marvelling in wonder at such beauty,

Man’s impelled to perform his vital duty,

Of awakening from this dire dream of life.

Through strong effort comes his prize for strife,

Grace descends and destroys sad ego mind,

Pilgrim’s freed and eternal peace does find.”

—Alan Jacobs, “Rose Garden”

Paula Marvelly: IT WOUD BE nice if you could outline the points in your life where there was some kind of spiritual meaning and the key points when you were able to see that there was something more than who you thought you were.

Alan Jacobs: My father was a religious man—he was an orthodox Jew and he used to take me to the synagogue every week from the age of five, so I had an input of spirituality from an early age.

During the war, I was evacuated to America and there I lapsed quite a lot because during that period I didn’t find very much. When I came back, I went to Malvern College and the Headmaster, whom I admired very much, was a truly spiritual Christian. When I joined his Divinity Class, he took an interest in me because he recognized that there was something that I was saying that was different. He invited me to his discussion group, so that was the first time I was involved in spiritual dialogue.

When I left school, I had to do my National Service. When I came back and returned to the synagogue, there was a new rabbi appointed called Rabbi Louis Jacobs, who was really outstanding. He was a great theologian and a profound thinker. Again, I joined his discussion group as something attracted me very much to what he was saying.

One day, there was a sermon he gave in which he said that we must not take for granted what we hear. We have to be our own authority and make our own enquiry, our own search for the truth. This impressed me very much because it wasn’t just a matter of accepting traditional teachings.

Then around that time, I had what I call the first “real experience”. I had started to do hatha yoga for keep fit purposes and one day I was sitting crossed legged in a meditative state and all of a sudden, I was enveloped by a very profound silence that held me. Then a voice spoke quite loudly within the silence and said, “Who am I?”

At the time, I didn’t quite know what to make of this. But I had a friend who was well up on spiritual matters and I told him about it and he said that I should go and see Kenneth Walker, who was one of the leading teachers of the Gurdjieff method in England. I was 27 at this point.

I went to Kenneth Walker and he asked me to come along to his discussion group. I was very impressed with him. I actually loved him in the sense that he as a very genuine person. I then got involved in the Gurdjieff Society as it seemed to fulfil all my needs. I liked the people and the teaching appealed to me and it turns you into someone with spiritual muscle.

PM: Which tradition did Gurdjieff draw on?

Alan Jacobs: Mainly Sufi but it’s a Westernized version that has been customized. He found the Sufis during his tour of the Middle East.

Fundamentally, the principles are that everything you do should be done with attention. Man is asleep and in order to wake up, it is a question of attention. There is a teaching where the central focus is called Self-Remembering. The effort is to remember the Self.

There were some good teachers there and I found myself being led into the hierarchy—I was made secretary of this and secretary of that. After eleven years, because I got to know the people who were running it, I came to see that the people were marvellous as teachers but when it came to their personal lives, there was a lot of power struggling, negativity and discontent.

Around that time, J. Krishnamurti appeared on the scene in England. He was teaching in Wimbledon and later at Brockwood Park. It occurred to me that I should really have a living master. In the Gurdjieff Society, Gurdjieff was dead and there was nobody who could really declare who had woken up or not, although they were advanced souls.

Krishnamurti seemed to be the answer for me at that point. He was a wonderful speaker, dynamic on the platform and everything he said seemed to make sense. The fundamental principle was awareness—you should be continuously aware of what’s going on internally, which in turn would lead to some kind of Self-knowledge. I did follow his teaching but again I got caught up in the machinery. I used to run a joint discussion group with an Indian called Kishor Parekh and we did this for a number of years. I also met Krishnamurti on two occasions.

At a certain point, I went to Russia. I was working as an art dealer at that time and visited the Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg. During my trip, I had oysters and I became very ill with hepatitis. My wife, who also followed these teachings with me, brought me a yoga magazine to read while I was recuperating and in it was a picture of Bhagavan Sri Ramana Maharshi. When I looked at the picture, it seemed to say, now you are ready for me.

Prior to this, I had already had two other “Who Am I?” experiences—the first time in a Douglas Harding workshop and the second with one of Douglas’ friends, Alan Rowlands, who was an Alexander Method teacher.

So by the third experience, I threw myself into Sri Ramana’s teaching and read everything I could and tried as best as I could to understand it. The mentor I had at this time was Sri V. Ganesan, who is the great nephew of Bhagavan, who wanted to start a foundation in England.

I was chosen to assist Nair Vasudevan, who had actually sat at Sri Ramana’s feet. But after three years or so of running the Ramana Maharshi Foundation, Nair Vasudevan wanted to give it up as he wanted to live in the country and go into retreat and write—he didn’t want to travel anymore up to London. So I asked Ganesan about who was going to run the Foundation from now on and he said that I was. I said that I wasn’t equipped so he said for me to go and see Robert Adams.

My wife had died suddenly in the interim period—she was my first wife and we had been married for twenty-three years and had three children. I did subsequently marry again to a Jungian practitioner and medical doctor—that marriage lasted for ten years but eventually broke down.

Then I met Jane Adams and we fell in love and so I left my second wife and moved in with Jane. Jane became the Secretary of the Ramana Maharshi Foundation UK.

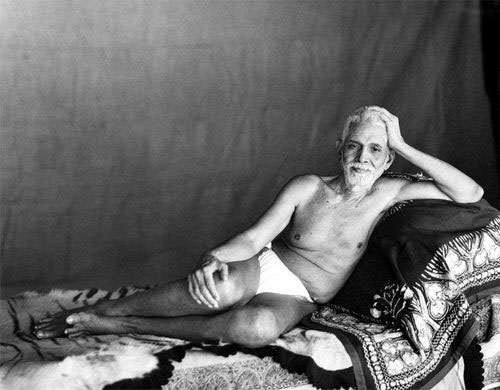

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

However, around this time, I started to go to the Ramanasramam in Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu, India, fairly regularly, once a year. On one particular time, I met an old friend there whom I trusted and said you have come at the right time, there’s a wonderful new teacher on the hill.

I took all this with a pinch of salt as I have heard all these stories before but he then told me that Mira Pagoux, Papaji’s second wife, had said that this new teacher was the only free being she had met in India since Papaji. So I thought I must go.

The teacher was Radha Ma. When I met her, I felt an immediate connection, as if something was coming from her that was sacred—it struck me deep in the heart. Again, she took a personal interest in me and spent some time correcting my view of the teaching and made me internalize much more of it than I had previously done.

I had been more or less a “half bhakta”, thinking God was mainly outside. Radha Ma pushed me inwards. After that, I kept contact with her continuously. I would go every year and she guided me on sadhana. We corresponded via email and I became one of her closest people in her circle.

So that’s the history of the search. When Ganesan eventually decided to give up the Foundation, I became the President. I have looked after the Ramana Maharshi Foundation UK now for twenty years. Jane and I also decided to live separately, although we are still very close friends.

I kept in touch with Radha Ma until her recent death by self-immolation. Nobody is entirely sure what happened to her. She was only forty-two.

The monastery in Tiruvannamalai, which she founded, wrote to me and said it was their view that it was a case of what is called jiva samadhi, which refers to someone of very high spiritual attainment who makes a decision to leave the body because they want to be on another plane of being so as to assist those they love. She felt she could do this more effectively from another place rather than from where she was.

She was fearless. She threw herself into the fire, laughing quite happily by all accounts. They did take her to hospital but the burning had gone too deep. And now people who were close to her are waiting to see if there is going to be any message from her. This is what the swamis in her monastery have told me and I believe them.

I was fairly recently invited to edit another great teacher, Rajini Menon’s great book, Face to Face With Reality. She is also a jnani, who answers questions by correspondence. Her email address is given at the end of the book, which was published by Yogi Impressions. We invited her to London where she made a great impression in our satsang. She has also made some excellent videos on YouTube.

Like Anandamayi Ma, all her sadhanas were achieved in a previous life. She gives the details of her awakening in the foreword to her book. I have written a preface as well. She is a remarkable woman. The book was endorsed by Swami Dayananda Saraswati, the leading authority on Vedanta at that time. It was a privilege to edit her book, especially as she was familiar with Sri Ramana Maharshi’s teaching having visited his ashram a number of times.

PM: So in your opinion, compared to all the people you have read, would you say that the teachings of Sri Ramana Maharshi are the highest and most profound?

Alan Jacobs: Yes, I am totally convinced. In the book I have written, Sri Ramana Maharshi: Supreme Guru, in my introduction, I make the case that traditionally, every thousand years, there appears on the planet a supreme guru.

Shankara was a little more than a thousand years ago—twelve hundred years or so—and what he did as a supreme guru was he codified the whole Advaita teaching from the Upanishads. He then went around India, setting up various monastic centres, establishing the Advaita Vedanta teaching and making it accessible for a long period.

Tradition also says that when the planet reaches a low point in the dharma, a sage appears of the highest calibre. Bhagavan comes at the turn of the last century, when we were moving into the First World War, the Second World War, atomic bombs and the holocaust, so this is a very low period indeed. He was also born on a festival of Lord Shiva.

What Sri Ramana has done as the supreme guru is that he started a renaissance in Advaita Vedanta. Before that, it was reserved for the brahmin initiates of gurus. He made it accessible to everybody. He deliberately made his teaching go to the West, through Paul Brunton and others, and then he brought Self-enquiry into the open.

For fifty years, Sri Ramana taught at Arunachala and has set the agenda for the next millennium, in the same way that Shankara did, so I do regard him as a supreme guru. The guru of gurus.

Anandamayi Ma, when she laid the foundation stone for Sri Ramana’s samadhi, made the comment that he was the sun and that they were only stars.

PM: So what are the tenets of Sri Ramana Maharshi’s teachings essentially?

Alan Jacobs: There are two backbone principles—one is the devotional aspect of surrender. We start from the principle that the Self is there in everyone but people don’t know it because it is occluded by the egotistic mind, the continuous chatter of the mind and all kinds of latent tendencies, which in the West we would call the subconscious. These create a cloud so people are not in touch with their real Self.

This real Self is in everybody and is the inner guru. The Bhagavad Gita says there is an inner guru in everybody. What actually happens is that if one surrenders to this inner guru, if you have sufficient faith to surrender to this inner guru within you, you then receive guidance.

Grace comes in proportion to the effort you make—you are actually led and the sadhana is directed. It is a gradual and graceful process because if it happened too quickly, the power of full Consciousness is too intense—the nervous system couldn’t take it. So it’s a gradual, graceful process of removing latent tendencies, which are called vasanas, through the surrender to the satguru in the heart.

Then, coupled with that, is the practice of Self-enquiry. Self-enquiry is quite simple—it is about turning the mind inwards to search for the source of the egotistic mind. But there’s no answer to the “Who Am I?” enquiry. Asking the question is sufficient because turning the mind inwards, little by little, you are drawn in the direction of the Self as the clearing process takes place.

This process is not quick, necessarily. It depends on how advanced the soul is and what previous sadhana has been done before, possibly in a previous life. Sri Ramana said that all his work had been done in a previous life.

Those two together—Self-enquiry and surrender—are the backbone of the teaching. Everything is centred on that.

PM: Are you saying that you have to have both?

Alan Jacobs: No. Sri Ramana did say you could achieve Self-realization through surrender alone but it has to be total. Self-enquiry is an aid to speed it up, to make it possible much more quickly.

Similarly, Self-enquiry on its own can also achieve it. According to Ganesan, Self-enquiry alone did bring some forty people or so to Self-realization. Two very notable sages were Papaji and Swami Ramdas but there have been many others. David Godman’s book, The Power of the Presence, gives all the details.

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 4.0] The Culturium

Alan Jacobs: Effort and grace are interlinked. You can’t actually do Self-enquiry in the conventional sense but you have to make the effort in that direction. As the Gita says, if the Self perceives that you want to achieve Self-realization, it becomes your friend. Then effort and grace become interlinked.

With the effort of Self-enquiry and Self-surrender, grace happens. So in other words, you are prompted to the next step, you’re given more understanding, you become more mature and you begin to see the end of it all in yourself. You find you have the possibility of accessing the Self to a certain point.

Sri Ramana has put it very succinctly—he says there is no effort without grace and no grace without effort.

PM: So what actually is grace?

Alan Jacobs: Grace is totally unmerited revelation. You appear to be stuck—you reach a kind of spiritual atrophy as if you don’t know quite what to do next. You’ve been thinking that you have been doing this and nothing is happening, that you’re still caught up in mind the whole time. Then, all of a sudden, you get some sort of insight and understanding and you are able to move on, with a completely fresh start. You become revitalized.

Then you may be directed to write books, to read, to meet certain people. The right circumstances arise and your life becomes ordered. That’s the grace.

Although no thought force goes in vain, you can’t do it on your own. You need the coup de grâce, the blow of grace, to actually complete it.

To come into the orbit of this teaching is itself grace. Anyone who comes into the orbit of the teaching is already under the influence of grace and little by little, they are led in the right direction.

PM: You talked about sadhana, which I know means spiritual practice. So what should one actually do?

Alan Jacobs: Sri Ramana gives various suggestions. Surrender we have already talked about, which is fairly simple. With Self-enquiry, there are various approaches that he gives—there are about five or six in total. Most importantly, he says, find the one that is easiest for you to get into the heart any way you can.

So the sadhana is to find the practice that you are comfortable with; however, if you have really surrendered, the prompting of which sadhana to choose will come.

I personally do what I call “diving into the heart” and I’ve written quite a bit about it—it’s quite a sophisticated approach. I also practise the Atma Vichara method or “Investigation into the Source of the Ego” as taught by Michael James.

PM: What does it involve?

Alan Jacobs: In a nutshell, Ganapati Muni, who was one of the great disciples of Bhagavan, asked for advice about sadhana. Sri Ramana said that if you are able to turn the mind inwards and dive into the heart endeavouring to reach the source of the ego, this is all that is necessary.

The advice is embodied in the Eki Sloka. In the ashram above the couch in the New Hall, it is engraved in gold on black slab:

In the Inmost core, the heart

Shines as Brahman alone,

As I-I, the Self aware

Enter deep into the heart

By search for Self, or diving deep,

With breath under check,

Thus abide ever in atman.

He mentions diving into the heart in several places in his literature: The Forty Verses and The Thirty Verses and elsewhere.

Sri Ramana also says that for those who are identified with their mind and body, they can take the spiritual heart to be on the right side of the chest. After realization, the heart is a synonym for the Self and it has no location—it’s the All if you like, without circumference.

Diving into the heart with the breath control is explained in The Technique of Maha Yoga, which is published by the ashram. The focus of attention is between the eyebrows, in the pineal gland or the crown chakra. When anybody is doing any attentive work or trying to solve a problem, that’s where their energy comes from. The Gita also talks about focusing on this particular point.

Watching the flow of breath controls and quietens the mind—one takes a big inhalation in and then with the focused attention, like a laser beam, this attention goes into the right side of the chest as deep as it can, and then after that, one exhales. That’s all that is really necessary. That can be repeated whenever one feels prompted to do it—it completely takes you back into the present moment.

When I was put in charge of the Foundation, I knew that I had to teach Self-enquiry and so I pondered for quite a while and this particular method appealed to me.

When I met Radha Ma, I told her what I was doing and she checked my practice and approved it. When I wrote the foreword to her book, she signed it and wrote, “Keep diving as much as you can.”

So I am very happy with it and it does work as far as I am concerned. This is my sadhana. But there is no one sadhana for everybody. Bhagavan never actually said you must do this—he just made suggestions. He said any guru who tells you what to do shouldn’t be trusted because those instructions actually form a barrier between your inner guru and your own understanding. It has to come from within.

PM: Perhaps we could discuss Neo Advaita?

Alan Jacobs: Neo Advaita is a customized version of the traditional Advaita teachings to suit its own needs. It’s come about because the West has not inherited the Indian tradition of spirituality. In India, every child knows the Bhagavad Gita and they are brought up in a religious atmosphere. So these teachings come quite naturally if someone is already spiritually inclined.

In the West, it is an Indian import, customized to suit the Western mind. What Neo Advaita does is that it takes the absolute position of Self-realization—there’s nothing to do, there’s nowhere to go, you are already it—but by doing so, they only consider the destination but have ignored the journey. The journey is the spiritual practice, which they sideline.

So therapeutically, if I say you are perfect as you are, it doesn’t matter what you do, it’s all perfect, everything is happening in your awareness, you feel very good about this. But this awareness where everything is happening is not the real awareness of the jnani—it’s actually a reflected awareness. Bhagavan makes it very clear, as does Shankara, that these tendencies of the egotistic mind are reflecting Consciousness.

The Neo Advaita teachers have got hold of these concepts but they are still speaking from the mind, not from the no-mind state. They are speaking from reflected Consciousness. So it has a therapeutic value, it introduces young people into a social atmosphere of enquiry, it gives them a certain introduction but then the mature ones move onto a more traditional teaching, such as Sri Ramana’s. There has to be some spiritual practice in order to make a connection with your own inner guru.

At the Foundation, we find that people come to us after a few years of paying their fee and going to satsang for their monthly fix. The Neo Advaita teachers are itinerant teachers—they are earning their livelihood by it so they ask for reasonably substantial donations.

Having said all this, I think nothing happens in the universe haphazardly. The West needs softening up—it’s not yet ready for the full Advaita teaching, so Neo Advaita should not be frowned upon or disregarded, although it’s fallacious and only goes some of the way. I think more and more people will move into traditional teaching and various people are pointing this out.

Dennis Waite, for example, has written a very fine book, The Jungle of Enlightenment, in which he clearly points out the differentiation between traditional teaching and Neo Advaita.

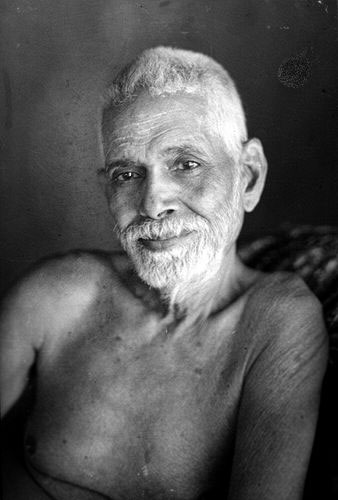

Photograph: [Public Domain]

Wikimedia Commons

Alan Jacobs: It is one of the key texts of the teaching and was written in Bhagavan’s own lifetime. Nan Yar is Tamil for “Who Am I?” and was produced in answer to questions. When Sri Ramana came out of samadhi, which he was in for about two years, he was able to answer questions but he wasn’t speaking. He was still in mouna, in silence. So he wrote the answers to the questions. Later, they were put in essay form, which he approved, as a continuous text.

When new people arrived at the ashram, they were given a copy of this text, so they had some understanding of his teaching. So it’s a cardinal text—it’s amplified in later texts he wrote but it’s one of the first.

PM: OK, let’s start.

Who Am I?

Alan Jacobs: This is the cardinal question. What Advaita is saying is that you are not the body, you are Brahman, you are God, you are the Self. But we are identified with the mind and body—we can’t help it, we are conditioned that way.

Shankara pointed out that the first thing a human being does is to identify with the physical form. Your parents say that’s little Paula there and Paula looks in the mirror and says, ah, yes, that’s me! She goes to school, has a name and the whole conditioning process goes on and on and on, continuously. So everybody is identified with the “I am the body” notion. This is how we all are.

“Who Am I?” is a counter question—it’s saying, no, you are not actually the body, you are the pure Self, God, Brahman, absolute Consciousness, whatever term you want to use. Also satchitananda—reality, existence, bliss—that’s who you really are. You are the divine. As Jesus says, the kingdom of heaven is within you.

So “Who Am I?” is a question designed to turn the mind inwards, to find out who I am really in truth. The body is simply a vehicle—we are born into a body on the planet for a specific purpose. And the specific purpose is to achieve Self-realization. If it doesn’t happen in this lifetime, it may happen in the next.

Tradition says that people who are brought into the orbit of this teaching are fairly ripe for it. In previous lives, they have reached some kind of equilibrium or balance between good deeds and bad deeds. And so grace comes and brings them into the orbit of the teaching. “Who Am I?” is the great weapon to turn the mind inwards, to penetrate through the complexity of identification, which is actually very strong and very powerful.

Bhagavan says that a knot, the granthi knot, is formed in the nervous system, which has to be severed.

PM: What is the nature of awareness?

Alan Jacobs: Everybody has kinesthetic awareness—every human being is born with it. So we are actually aware in a rough sort of way of everything that is happening. We receive impressions and we are aware of them.

We can increase awareness—hatha yoga increases your awareness by which you become aware of your movements, your limbs, your body. A teacher like J. Krishnamurti, for example, taught that you should be aware of everything you are saying and feeling as it happens, that there should be continuous awareness. Douglas Harding said the same.

So awareness can be increased. We are given a natural awareness—kinesthetic awareness in medical terms—but pure awareness is the Self, when it reaches its full intensity. The essential “I Am-ness” is pure awareness. This is the teaching of all the great sages, whether it is Sri Ramana, Nisargadatta Maharaj, or whomever—they talk about pure conscious awareness.

So pure awareness is a synonym for the Self but most of the time, it is mixed up with egotism and identification.

PM: When will the realization of the Self be gained?

Alan Jacobs: This is when the Self chooses. In other words, the inner guru is watching and guiding the whole process and, at a certain moment, it will know that a particular soul is ready for Self-realization, which is a major perspective shift. Then one reaches the no-mind state of satchitananda.

So it will happen when the Self chooses and is ready—the whole of sadhana is a preparation for that. Rumi, who was a great jnani from the Sufi tradition, said to his disciples that if any of them got what they wanted at that moment, it would kill them. This is because the Self is so intense, so powerful.

Even Bhagavan said it’s like an elephant going into a thatched cottage. So you really need to have your nervous system attuned by Self-enquiry and surrender.

PM: Will there not be realization of the Self while the world is there (taken as real)?

Alan Jacobs: In the first instance, we believe the world is real—this is the normal response of every human being that is born, that they are born into a real world. At a certain point when they come into the orbit of this teaching, this reality is questioned. We begin to see that we are living in a world that is created by the senses, that the sensorial apparatus and the organs of cognition are creating the world.

Quantum Physics tells us that this chair is not a solid object—it is actually a mass of electrons all swirling around in a bit of space. But if I touch it, it feels very solid. Again, Western Idealism philosophy, in particular the German Idealists like Kant and Schopenhauer, proved that space, time and causation are actually inbuilt into the organ of cognition, so automatically we create a sense of space.

We see events in succession and thus a sense of time is created but it is artificial, it’s a convenient measurement. Similarly with causation. Even animals make a connection between two events—cause and effect. We do the same, which creates what we call maya, the illusion of the world.

The sensorial apparatus is very limited for a human being. Animals in some cases have much greater sensorial powers than we have. Every animal creates its own universe—a cat has its own particular world, so does a dog, an eagle and so on. The human being lives in a manmade world.

When we talk about life on other planets, we can’t actually see any life because our sensorial apparatus won’t be able to perceive it since all our scientific apparatuses are only sensorial extensions of our own selves. In fact, there are all kinds of things going on that we can’t sense. In this very room, there are radio waves, high frequency waves, etc.

So we begin to question the reality of the world and see it as a representation on the screen of Consciousness. But is it really real?

Advaita says that the definition of reality is that it doesn’t change, it endures, it’s immutable, it’s eternal—this is what reality really means. All this that we see is in a state of flux—the ancient Greeks knew that. It all goes back to Heraclitus.

Again, Quantum Physics also supports this. So we then can say that the world isn’t as real as we thought it was; however, this is a provisional position. Bhagavan recommends that because we are so caught up in the world, identified with the world, that as a provisional position, we ought to see the world as unreal at this point, a dream. And although we go on living as if it is real, at the back of mind we know it is not real. This is a point I also learnt from Ramesh Balsekar.

After Self-realization, the world becomes real again because the jnani sees the substratum of the world as Brahman, in the sense that everything becomes illuminated, is all light. Christ was always talking about light. In modern times, we don’t talk about light, we talk about Consciousness.

Zen puts it beautifully. First there is a mountain. Upon examination, you begin to see that it’s a mass of electrons in a state of flux, so there is no mountain. Then the third stage, when you see Brahman as the substrate, there is a mountain again.

PM: What is the nature of the mind?

Alan Jacobs: The mind has two functions—it’s an instrument that contains intellectual discrimination and reason, all centred in the brain. We need these to navigate through the dream of life. All our decisions are made with the mind—problem solving, earning a living and so on. So in that sense, the mind is a great friend.

But the paradox is that the mind is also the mischievous monkey mind, as they like to call it. It is in a continuous state of chatter and self-reflection, creating havoc. It gets worried, it has fears about the future, it doesn’t like that but it does like this, and so on and so forth. So the mind is not a friend, it’s a plague.

The mind is all put under one umbrella word—ego. Ego is a word that is fashionable in Jungian psychology. It combines all the feelings of “I”—I am going to do this, I am going for a walk, I am going to have supper, I am going to tell him what I think of him, I am going to write a letter. Every time we say the word “I”, we are telling a lie, in a sense. It’s this false identification with the body.

So the mind and the ego have become linked—the teaching refers to the egotistic mind and the two have become synonymous. With Self-realization, there is a perspective shift—the mind changes. Bhagavan says it’s like looking at the moon at midday. It’s harmless, it’s a burnt-out rope, it’s no longer this chattering, mischievous mind.

Ramakrishna said for most people, the mind is the master but it should become the servant. There is a perspective shift whereby the mind becomes only an instrument because you are now living from the no-mind state.

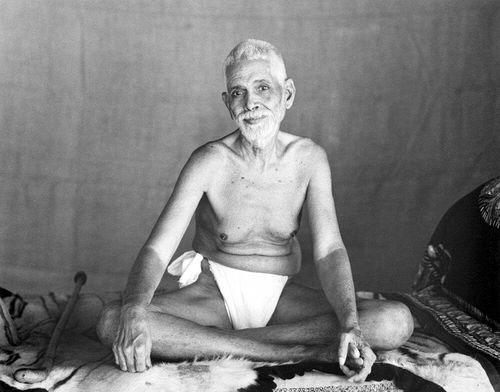

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 4.0] The Culturium

Alan Jacobs: The great advice the sages give is be still, be quiet. In the Book of Psalms, it says, be still and know that I am God. So to be still, to be the silent mind, the quiet mind, is the aim of the teaching.

There are various devices for this. One is a mantra. If you say a mantra, which has a certain potency, the mind can’t chatter because if you are saying, Om Namah Shivaya, the chattering mind can’t get in. At a certain point, the mantra stops and there is just the silence remaining.

The other one is watching the flow of the breath. Bhagavan said that thought and breath come from the same source of energy. If you just watch the flow of the breath coming in and out of the nostrils, the mind automatically quietens down. So if you are in an agitated state, just watch the flow of your breath. If you can’t get to sleep at night, instead of chattering to your own mind and having a dialogue that keeps you awake, just watch the flow of your breath.

Another other one is the hatha yoga technique, where you put the tip of your tongue into the roof or the palate of your mouth. It’s like a switch that turns off your mind.

Eventually, when the chattering mind is extinguished, the mind is quiet. The no-mind state is relatively silent, as far as we know, though we don’t know anything about the no-mind state until we get there—it’s only speculation.

PM: What is the means for constantly holding on to the thought, “Who am I?”

Alan Jacobs: It is a matter of attention. A lot of people who practise meditation increase their power of attention—maybe they start off by looking at a photograph of Bhagavan or the wick of a candle. If you develop this power of attention, you can turn the mind inward much more frequently and the mind will become quiet.

Some sages advocate continuously putting the attention on the Self and they are absolutely right; however, for most people they can’t put their attention on the Self because they hit a wall of all the various tendencies, so you have to penetrate through first before you can get to the pulsation.

My practice of diving in the heart is a radical approach towards getting there because it is using the power of the breath. The prana is very important, very powerful. Speaking to some people in the ashram, they told me that they never do any effort without using the prana, so it is an extra focus.

PM: The residual impressions (thoughts) of objects appear to move like the waves of an ocean. When will all of them get destroyed?

Alan Jacobs: This is a forecast of the Self-realized state. Most classical texts use the ocean as a metaphor for the Self—they talk about the waves on the ocean and then diving into the ocean. The Ashtavakra Gita is all ocean metaphor.

When Self-realization happens, the ocean becomes tranquil and quiet, like the silent mind, the state of the jnani. And yet this doesn’t mean that he doesn’t interact in life—he’s just not identified with it. Karma yoga says you play a role.

There’s also a line in Jean-Paul Sartre where he is in his favourite café and he points and says, that man over there is playing the role of being a waiter. Most people in their professional careers are playing a role—when they go home at night, they drop the role totally.

Karma yoga is playing the role you are given without identification, without attachment, without thinking about the result. You just play the role that you are given—it may be a professional role, a parental role, a child role, a bread roll, a bankroll.

Actually, the mind is a bundle of thoughts and we have a role for every situation—so whatever situation you find yourself in, you have an appropriate response. Jean Klein said you never have to worry about personality—it always responds appropriately. You go to a cocktail party, the role comes out, with the boyfriend another one, with your boss another one as well.

We are playing these roles continuously—there’s a bundle of them working all the time as laid-down programmes. The whole basis of NLP [Neuro Linguistic Programming] of which I am a practitioner, is all based on observing these different roles and getting rid of all the negative ones and affirming the positive. A lot of people have negative roles and they love their misery and suffering—they actually enjoy it and wallow in it.

The key with karma yoga is that you act your role without attachment, just like an actor on the stage. Laurence Olivier, when he played Hamlet, was still Laurence Olivier behind it all.

PM: Is it possible for the residual impressions of objects that come from the beginningless time, as it were, to be resolved and for one to remain as the pure Self?

I would also like to ask as an adjunct to this point that when there is Self-realization, are there still waves on the ocean or is it that there is simply non-attachment to those waves?

Alan Jacobs: Anyone who is Self-realized doesn’t ever make a claim to being Self-realized. Bhagavan said, do you feel love and peace in their presence—that’s the test. Then you are attracted to that person because you feel some kind of power.

One senses that there aren’t any waves with these people—it’s all love and peace. When they act the role, they are not identified with it. So if for some reason they get slightly angry, it’s a role-playing anger. Even Sri Ramana got angry on a few occasions.

I think the point is that there is a distance, a space between what is going on; however, I don’t make any pretence of Self-realization myself so I can’t really answer. I am an ajnani who is working towards Self-realization.

PM: How long should Self-enquiry be practised?

Alan Jacobs: As often as you get the impulse. Paradoxically, you can’t do Self-enquiry, you only have an impulse. All effort is actually impelled from within—you can’t “do” this teaching. The paradox is that you have to do the best you can, knowing that you are not the doer.

PM: What is the nature of the Self?

Alan Jacobs: The highest definition is the Self is Brahman or the Absolute. In Western theology, you could say the Godhead. Meister Eckhart calls it the Godhead. Almighty God is the same as Ishvara, which is a provisional position that you adopt for devotional purposes until you reach Brahman, the Absolute.

The other definition in Advaita teaching is satchitananda. Sat is reality or sheer existence. At this moment I know that I exist. I am here now—that’s reality. Heidegger and the Existentialists were all interested in this whole question of what is existence.

Chit is Consciousness. Consciousness is synonymous with awareness—it is the screen on which all this is happening. Bhagavan uses the metaphor of the cinema. You go to a cinema show and see all this happening on the screen—fires, rapes, burglaries, whatever, but the screen is not affected. It’s all pictures on the screen of Consciousness.

Ananda is bliss or love. This is an ecstatic state when you are out of the normal antics of the mind, where you are in a higher state, which is peaceful, quiet and has qualities of pure silence, unconditional love and ecstasy.

Photograph: [Public Domain] Wikimedia Commons

Alan Jacobs: Well, yes. Let’s put it this way—this teaching is rooted in determinism. Fifty percent of Western philosophers are determinists. They say we are all governed by necessity and that free will is an illusion. We think we have got free will but it is part of the structure of determinism.

Who is in control of the determination? The adjunct of Brahman is called Ishvara, which in theological Christian terms is Almighty God, who according to Bhagavan, predetermines the life of each soul, or jiva, for their spiritual development. So the life you are given is actually your sadhana, your spiritual path.

Everything that happens is preordained. You can’t look at the world horizontally—from this perspective, for example, it looks terrible, with horrible things going on all the time. People say there can’t be a God of love—just look at all the suffering.

In actual fact, it is a vertical process. There’s an individual karma for each soul from birth to death but you don’t actually see what’s happening in that life. All you see is, for example, somebody being run over, and you say how terrible but that was necessary in the karma at that point.

So God is actually controlling the whole world. Bhagavan says that not one atom, not one molecule moves without permission. It’s all choreographed down to the last detail. But we can’t understand it—it is beyond the mind because we don’t know the mind of God.

Bhagavan said that once you come into the orbit of the teaching, you are on the way out to another plane of being, which isn’t samsara, the whirlpool of recycling birth and death. You move to another state of being, another plane of existence. People asked Bhagavan what he meant by this to which he replied that you would only find out when you get there.

PM: What is non-attachment?

Alan Jacobs: That’s a bit like karma yoga. If you are playing the role, you are not identified, attached to the role. You shouldn’t be attached to any object—they are only given to us for our convenience. So when you say “me” or “my”, particularly “my”, you are attached.

Again, paradoxically, Douglas Harding used to say that the walls of Advaita are built on bricks of paradox. We have to act in the world quite normally and behave like everybody else—this is my house, my room, my television set—but really, we shouldn’t be attached to any object or to any person. It doesn’t mean that you don’t value or love them but real love is without attachment. Attachment is removing the egoistic element from possession.

PM: Is there any use for reading books for those who long for release?

Alan Jacobs: Yes. Bhagavan said that the first step you should make is having clear intellectual understanding of Advaita Vedanta. He did write certain texts to give this—Talks, the collected works of his own writings, etc. He also translated some of the key works of Shankara as well. So one needs to read books in order to have a clear understanding.

After that, you only read books to enrich a particular aspect of the teachings you are interested in. He said that for those whose minds are not very quiet, then they can quieten them down by reading the right book. Bhagavan himself was very interested in poetry.

The trouble is, if you become a bookworm, you just repeat stuff you have read in books—there are people who can give lectures on Advaita Vedanta who are professors but there is no practice, they have just read it all from a text. That kind of reading is useless. There is a danger that there is too much reading but a little is definitely necessary.

PM: What is happiness?

Alan Jacobs: Happiness is our real nature, so if we realize the Self, we are purely happy. Happiness is peace, bliss, ananda. Being in touch with the Self is the real happiness.

PM: What is wisdom insight (jnana drsti)?

Alan Jacobs: This is the gift of the subtle mind, where there is more insight, more intelligence. If you read Ramana’s Talks or Robert Adams’ books, or any of the sages in literature, you find this subtlety of observation.

PM: What is the relation between desirelessness and wisdom?

Alan Jacobs: Vasanas or latent tendencies—there are benign ones and malign ones. There’s nothing wrong with the benign asanas, for example, love of poetry, music, literature, art. They don’t have to be renounced. But there are also malign vasanas, which are desires—greed for wealth, lust for its own sake where there is no love involved, ambition. These desires are malign because they lead to a huge identification and can rule and destroy people’s lives.

Ideally one should lose the malign vasanas. Just accept what is given to you in the normal course of life as a gift—it doesn’t mean you have to be identified with it.

It’s all to do with balance. The key to the teaching is equanimity, to be contented, not to move between the opposite swings, the opposite polarities of like and dislike. It’s about being in the middle. This is a sattvic state, being in the centre.

PM: What is the difference between enquiry and meditation?

Alan Jacobs: Enquiry we have already discussed. Meditation can be any form. There are lots of different forms of meditation. They can be self-observational meditation like vipassana, where you just watch what is happening, what is coming up, impartially without any judgement.

Another meditation would be increased concentration or quietening of the mind. There are many forms. I suppose the highest form of meditation is Self-enquiry.

PM: What is release?

Alan Jacobs: Release is removing the attachment to the mind-body and then you are a free being, you are you free. Self-realization is the ultimate liberation, the ultimate freedom, the ultimate release.

Photograph: [CC BY-SA 4.0] The Culturium

Post Notes

- Alan Jacobs’ Amazon page

- Alan Jacobs’ poetry blog

- The Ramana Maharshi Foundation, UK

- Ramanasramam official website

- Alan Jacobs: Heart of Heart’s Chalice of Love’s Fire

- Alan Jacobs: Poems to Make the Soul Sing

- Upahar: Bright Like a Million Suns

- Sri V. Ganesan: The Ultimate Question

- Paula Marvelly: A Singular Man

- W. Somerset Maugham: The Saint

- Paula Marvelly: Rendezvous With Ramana, Part I

- René Daumal: Mount Analogue

- Marsilio Ficino: Know Thyself