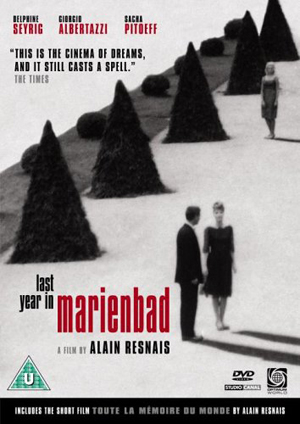

Alain Resnais, Last Year at Marienbad

Is all that we see or seem but a dream within a dream?

I walk on, once again, down these corridors, through these halls, these galleries, in this structure of another century, this enormous, luxurious, baroque, lugubrious hotel, where corridors succeed endless corridors—silent deserted corridors overloaded with a dim, cold ornamentation of woodwork, stucco, moldings, marble, black mirrors, dark paintings, columns, heavy hangings, sculptured door frames, series of doorways, galleries, transverse corridors that open in turn on empty salons, rooms overloaded with an ornamentation from another century …

LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD (L’Année Dernière à Marienbad) (1961) is an utterly beguiling and yet deeply unsettling movie. Like any great work of cinema, it rests on a seemingly simple plot, but which, upon investigation, proves to be as visually compelling as an Escher lithograph, with its geometrical and labyrinthine composition, leading us into an unresolvable, infinite regress.

Located in a baroque chateau, X (played by Giorgio Albertazzi) has returned to claim his inamorata, A (played by Delphine Seyrig), with whom he has had a passionate affair the previous year; however, A is currently involved with another man, M (played by Sacha Pitoëff), who is possibly her husband and discreetly watches over her every move.

Despite the fact that it is A, according to X, who has arranged the time and place of their rendezvous, she now claims to have no knowledge of having ever met him—in Marienbad or any other such place—let alone having any form of clandestine arrangement.

A Rashomonesque examination of an Oedipal love triangle on the surface, watching Last Year at Marienbad is in actuality a profound meditation upon the nature of reality, time, memory and personal identity, symbolized through its stylistic use of monochromatic montage, architectural symmetry and atonal musical score.

Image: © Alain Resnais

La Nouvelle Vague

Created by the artistic collaboration of the French Rive Gauche director, Alain Resnais (3rd June 1922–1st March 2014), and the Nouveau Roman author, Alain Robbe-Grillet (18th August 1922–18th February 2008), there have been a plethora of philosophical, phenomenological and psychoanalytical interpretations of the film, which still continues to enchant and bewilder critics alike, some heralding it a masterpiece of French New Wave modernism, whilst others condemning it as an exercise in pretentious self-indulgence.

Between these walls covered with woodwork, stucco, moldings, pictures, framed prints, among which I was walking—among which I was already waiting for you, very far away from this setting where I now stand, in front of you, still waiting for the man who will no longer come, who no longer threatens to come to separate us again, to tear you away from me. Are you coming?

The film opens with Rosmer, the enactment of a condensed version of Rosmersholm, a play by Henrik Ibsen about guilt, divided love and a fated suicide pact, driven by the ghosts and memories of the past. Marienbad similarly plays with repressed desire and shifting allegiance, whereby A is finally convinced by X’s relentless persuasion and reconstruction of former events, ending with their elopement into an unknown fate.

Like Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream—a drama focusing on love, time, reality and the loss of personal identity, which also features a play within a play—we are immediately alerted to the fact that all is not quite what it seems. Indeed, in the preface to the screenplay, Robbe-Grillet states that he was inspired by Resnais’ former work because, “I recognized in it the attempt to construct a purely mental space and time, those of the dream, perhaps, or of memory, those of all affective life—without being overly concerned with traditional causal links or with an absolute narrative chronology.”

And thus, in the manner of the Russian filmmaker, Andrei Tarkovsky, the film evolves and develops not through a linear, chronological sequence of circumstances but rather the repeated depiction of scenes, dialogue, fantasies and music, creating a mesmeric tableau oscillating between perception and memory, dream and reality, past and present, even life and death.

These whisperings, worse than silence, that you’re imprisoning me in. These days, worse than death, that we’re living through here side by side, you and I, like coffins laid side by side underground in a frozen garden …

Image: © Alain Resnais

Femme fatale

As the tension mounts between the two protagonists, the assembled guests—immaculately dressed in evening gowns and tuxedos, designed by Coco Chanel—continue with their parlour games and marksmanship competitions, making polite conversation and dancing the Viennese waltz. The mise en scène resembles more the backdrop for a Vogue fashion shoot with its theatrical and elaborate ornamentation, its cast a collection of mannequins, trapped in a timeless universe, whose only purpose is to create an atmosphere of bourgeois decadence.

Indeed, everything in Marienbad has the veneer of artifice, devoid of emotion and feeling against which X is forever struggling, in order to release A from her gilded cage.

One evening, I went up to your bedroom … I had warned you I would come. You didn’t answer. When I came I found all the doors ajar … You’ve always been afraid. But I loved your fear that evening. I watched you, letting you struggle a little … I loved you. There was something in your eyes, you were alive … finally … I took you, half by force … Oh no … Probably it wasn’t by force … But you’re the only one who knows that.

The film now takes on a darker perspective with the implication of an act of sexual violence and aggravated force. Our feelings towards X are changing; we empathize with A’s ambivalence and distrust of his character and the fact that we still don’t even know his proper name. The boundaries between fact and fiction are blurring, making us question whether anything in Marienbad is in fact objectively real.

Image: © Alain Resnais

Je pense, donc je suis

In his brilliant analysis, Jorn K. Bramann declares that the structure of the film reflects the philosophical theories of René Descartes:

To the extent that this ‘purely mental space and time’ is cut off from any objective reality, against which it can be checked, i. e., to the extent that it is impossible within the film to determine with certainty whether any event is real or fictional, the flow of images, thoughts and events of Last Year at Marienbad is the equivalent of the self-contained, solitary mind of the Cartesian self.

The whole sequence of events conveyed by the film is like the interior monologue of one individual—presumably that of X. Descartes holds that all we can really be certain of is that we experience something—the content of our minds. Whether the content of my mind corresponds to anything outside my mind I cannot possibly know. I seem to have the experience of seeing a world and other people around me but I can never be entirely sure whether these experiences are merely mental, like a dream, or whether they are caused by real things and people outside my mind.

The world experienced by a Cartesian, in other words, is in principle like the flow of events and images presented in Last Year at Marienbad. It is a world which I cannot leave and the reality of which (its ontological status) I cannot determine. It is a world in which nothing may be real and in which I may, indeed, be the only existing being.

The whole story of Last Year at Marienbad is ultimately the dialectic of the Cartesian mind—its imprisonment in itself, and its anxious attempts to get out and to find a real world and other human beings. X’s important desire is not to win A, it is not an amorous passion. It is, rather, the Cartesian’s attempt to escape from solipsism.

X’s courtship is an ontological quest. His anxiety is that of the Cartesian individual who wants to make sure that there is something real beyond the contents of his own mind and that there are other beings like himself. The hotel is the labyrinth of the Cartesian mind that inspires the search for a way out but that also reveals every seeming exit as yet another part of the labyrinth. This is also shown by another way in which X tries to escape from the Cartesian world.

—Jorn K. Bramann, The Educating Rita Workbook

The whole story of Last Year in Marienbad is indeed a dialectic of the mind—everything X perceives is ultimately a mental projection, a magic trick, a dream. Thus, despite its avant-garde elegance and cinematographic élan, the film’s philosophical substratum makes Last Year in Marienbad an absolute masterpiece of modernist cinema.

Image: © Alain Resnais

À la recherche du temps perdu

In the closing scenes, at the stroke of midnight, released from their aesthetic asylum into the seemingly arcadian garden beyond, the lovers stumble in the darkness. Will they encounter Death, as Ibsen’s fated couple do, or will they discover Life, free at last from the confines of their labyrinthine ordeal? Perhaps they have merely awakened from a dream only to be cast in yet another one? As Jorn K. Bramann observes:

In his famous ‘Dream Argument’, Descartes reminds us that waking up from a dream can itself be part of a dream. No matter how awake we feel, we may still be asleep and in the grip of a dream. There is no possible way of getting ‘outside’ of our minds to determine in what state we actually are; inescapably we remain imprisoned in our minds.

It is similar with X and A’s escape from the hotel. Although X and A rebel against the confinements of the world of the castle and although they intend to leave their present life by going ‘somewhere else’, their futile rebellion is nothing more than yet another variation of life at the hotel. The end of the theatrical and ceremonial life is itself a ritual and part of the show.

—Jorn K. Bramann, The Educating Rita Workbook

The lack of any coherent resolution is the only meaningful way the film can ever end. And thus, we witness the lovers trapped yet again in space and time, illusion and darkness, ensnared by their collective fate.

The park of this hotel was a kind of garden à la francaise without any trees or flowers, without any foliage … Gravel, stone, marble and straight lines marked out rigid spaces, surfaces without mystery. It seemed, at first glance, impossible to get lost here … down straight paths, between the statues with frozen gestures and the granite slabs, where you were now already getting lost, forever, in the calm night, alone with me …

Post Notes

- Jean Cocteau: The Art of Cinema

- Abbas Kiarostami: Certified Copy

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinematic Genius

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Julian Schnabel: At Eternity’s Gate

- Lisandro Alonso: Jauja

- Maya Deren: A Study in Choreography for Camera

- Kaneto Shindo: The Naked Island

- Marie Menken: Glimpse of the Garden