TateShots, Agnes Martin

A beautiful mind

When I think of art I think of beauty. Beauty is the mystery of life. It is not in the eye it is in the mind. In our minds there is awareness of perfection.

We respond to beauty with emotion. Beauty speaks a message to us. We are confused about this message because of distractions …

It is not in the role of an artist to worry about life—to feel responsible for creating a better world. This is a very serious distraction. All of your conditioning has been directed toward intellectual living. This is useless in art work. All human knowedge is useless in art work. Concepts, relationships, categories, classifications, deductions are distractions of mind that we wish to hold free for inspiration …

The way of an artist is an entirely different way. It is a way of surrender. He must surrender to his own mind.

—Agnes Martin, ‘Beauty is the Mystery of Life’

BLUE … BLUE … BLUE … How I stand in reverence before the beauteousness that is the colour blue. As the Russian painter, Wassily Kandinsky, wrote in his creed to the creative life, Concerning the Spiritual in Art, enlightening us with his own ruminations on the sublimest of shades in the painter’s palette: “The deeper the blue becomes, the more strongly it calls man towards the infinite, awakening in him a desire for the pure and, finally, for the supernatural … The brighter it becomes, the more it loses its sound, until it turns into silent stillness and becomes white.”

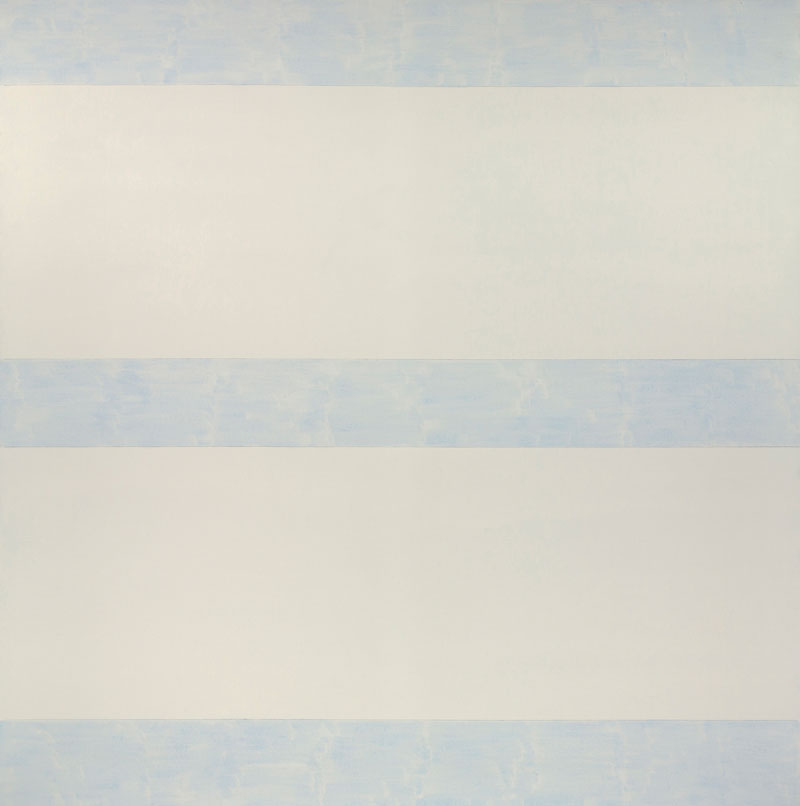

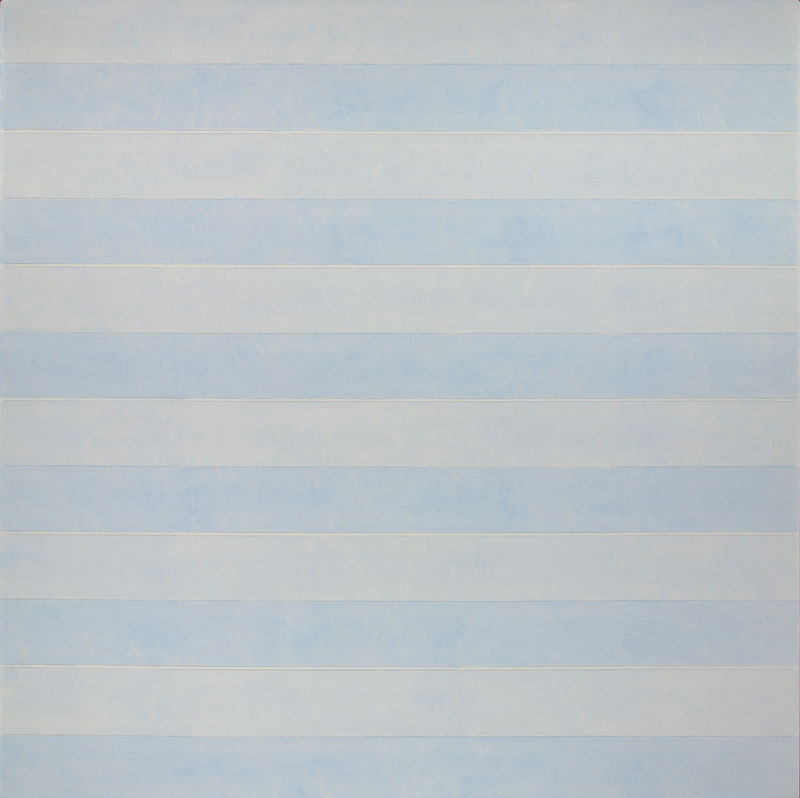

In the final phase of her artistic career for which she is probably best known, Agnes Bernice Martin (22nd March 1912–16th December 2004) painted her own homage to the most ethereal pigment in a series of “bleached out blues” encapsulating her unique ode to creative inspiration and, more specifically, the path to self-knowledge through surrendering to the inherent beauty within the depths of our very own minds.

c. 1993-1994, acrylic on linen, 60 1/16 in. x 60 1/16 in., Gift of the Artist.

Photograph: © Collection of the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico

Cradled on the mountain I can rest

Solitude and freedom are the same

under every fallen leaf

Others do not really exist in solitude, I do not exist

no thinking of others even when they are there, no interruption

a mystic and a solitary person are the same

Night, shelterless, wandering

I, like the deer, looked

finding less and less

living is grazing

memory is chewing cud

wandering away from everything

giving up everything

not me anymore, any of it

retired ego, wandering

on the mountain

no more conquests, no longer an enemy to anyone

ego retired, wandering

no longer a friend, master, slave

all the opposites dead to the world and himself unresponsible

perhaps I can now really enjoy sailing

adventure in the dark

very exciting

—Agnes Martin, ‘The Untroubled Mind’

Born in Macklin in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, as a child growing up under the influence of a stern and heartless mother, Agnes had long periods of enforced isolation that drove her to look deep within herself for solace. Not unlike Antony Gormley, who similarly endured periods of enforced solitude at an early age, it instilled within her renunciation and self-discpline, qualities that would serve her right through until the end of her days.

Moving to the United States in her twenties, Agnes worked as a teacher for several years before deciding at thirty to become an artist. Working initially in New Mexico making abstract landscapes and still lives, she finally settled at 45 in New York in a studio in the Coenties Slip. Little of her work survives from this period, owing to her habit of destroying anything that failed to match up to her vision of artistic perfection. After the death of a close friend, the abstract painter Ad Reinhardt in 1967, she abandoned the art world altogether and hit the road in a pickup truck, effectively resurfacing in New Mexico again on a remote mesa at 56 where, after building herself an adobe dwelling and log-cabin studio, she developed her five-foot square paintings for which she is best known. Agnes continued to live in solitude until the very end of her life, save for her final few years in a retirement community shortly before her death at 92.

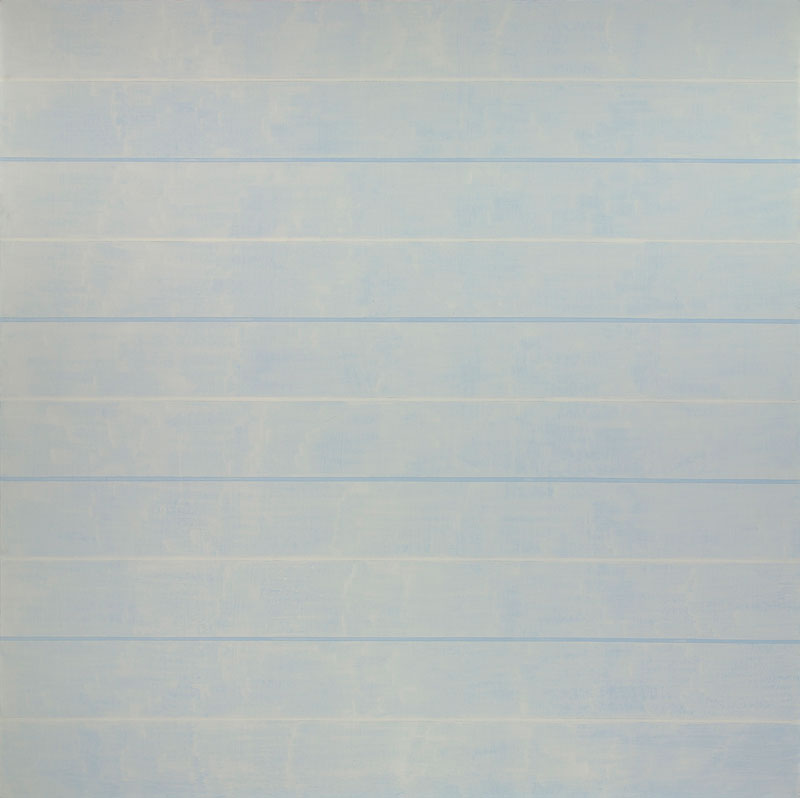

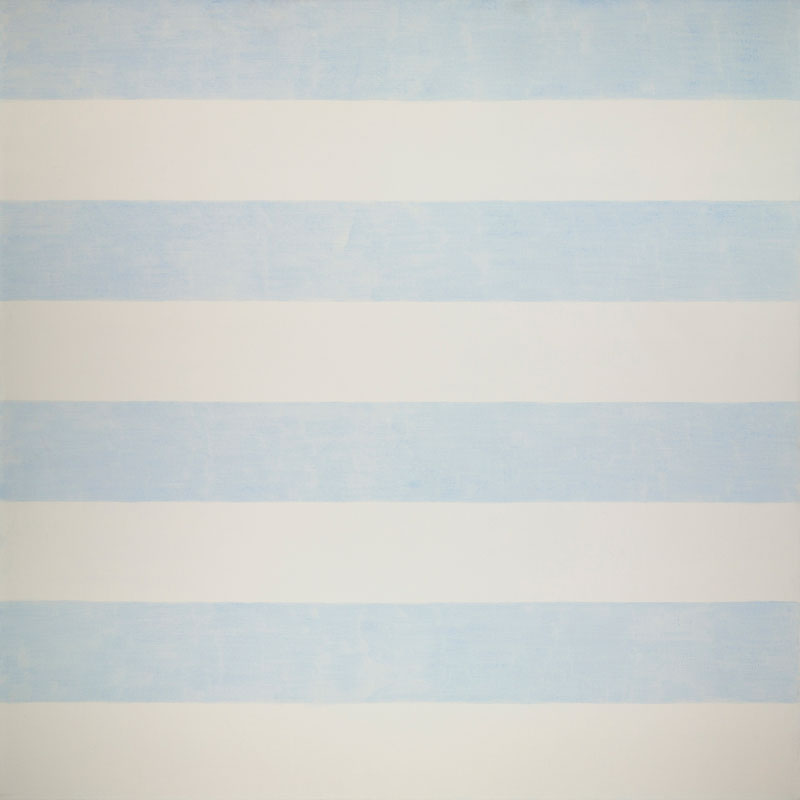

c. 1993-1994, acrylic on linen, 60 1/16 in. x 60 1/16 in., Gift of the Artist.

Photograph: © Collection of the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico

Helplessness, even a mild state of helplessness is extremely hard to bear. Moments of helplessness are moments of blindness. One feels as though something terrible has happened without knowing what it is. One feels as though one is in the outer darkness or as though one has made some terrible error—a fatal error. Our great help that we leaned on in the dark has deserted us and we are in a complete panic and we feel that we have got to have help …

But helplessness when fear and dread have run their course, as all passions do, is the most rewarding state of all. It is a time when our most tenacious prejudices are overcome. Our most tightly gripped resistances come under the knife and we are made more free. Our lack of independence in helplessness is our most detrimental weakness from the standpoint of art work. Stated positively, independence is the most essential character trait in an artist.

Although helplessness is the most important state of mind the holiday state of mind is the most efficacious for artists: ‘Free and easy wandering’ it is called by the Chinese sage Chuang Tzu. In free and easy wandering there is only freshness and adventure. It is really awareness of perfection within the mind. Everyone has memories of adventures within the mind, strange and pleasant memories, but not everyone is aware of adventures within the mind when they happen …

The solitary life is full of terrors. If you went walking with someone that would be one thing but if you went walking alone in a lonely place that would be an entirely different thing. If you were not completely distracted you would surely feel ‘the fear’ part of the time. I am not now speaking of the fear and dread of helplessness which is a very unusual state of mind. I am speaking of pervasive fear that is always with us. It is a constant state of mind of which we are not aware when we are with others. We are used to this fear and we know that when we are with anyone else, even a stranger, we do not have it. That is all that we do know about it. In solitude this fear is lived and finally understood.

—Agnes Martin, ‘On the Perfection Underlying Life’

Agnes was no stranger to feelings of fear and helplessness throughout her creative life. Diagnosed as a paranoid schizophrenic in early adulthood, she was bedevilled by the interior dialogues and disarray of her condition. Despite the fact that the “voices” did not interfere directly with her artistic output, she wrestled with catatonic trances, auditory hallucinations and bouts of depression, which instigated an investigation into the nature of the mind and the capriciousness of the ego. Indeed, deeply influenced by the teachings of Taoism and Zen Buddhism, Agnes sought to deconstruct the very fabric of the sense of self, terrifying as it was, in order to rest in the perfected state of the “vacant mind” and subsequently present the experience through her impeccable art.

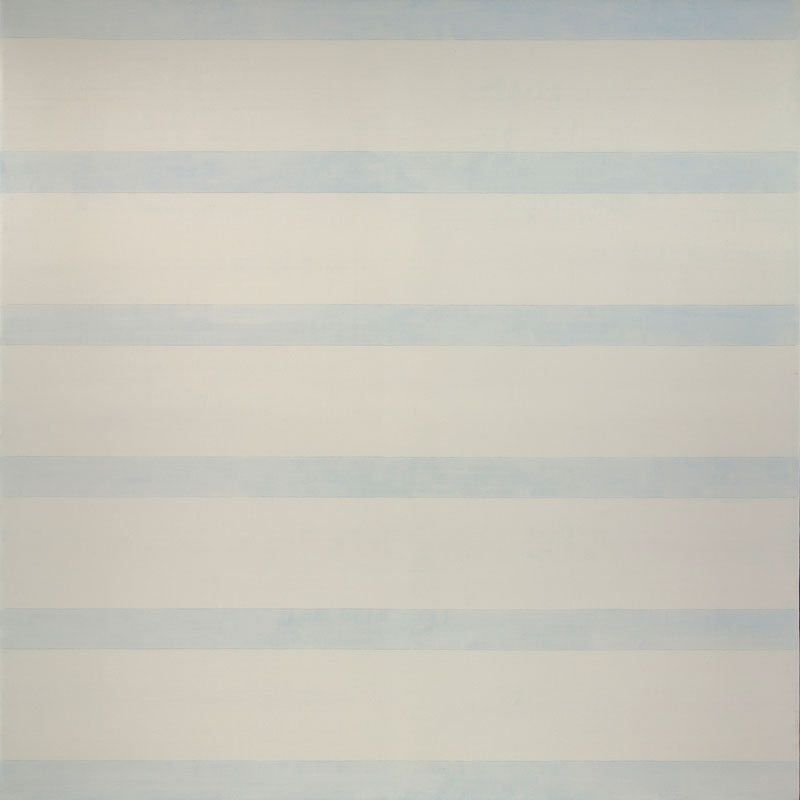

Furthermore, her self-imposed material deprivation, including periods of no electricity or running water, a meagre diet and a solitary life that would not even tolerate the presence of a pet, the manner in which her paintings eventually evolved into the harmoniously aligned horizontal stripes of varying shades of serene cerulean belie the fact that they were borne of physical hardship and mental turbulence.

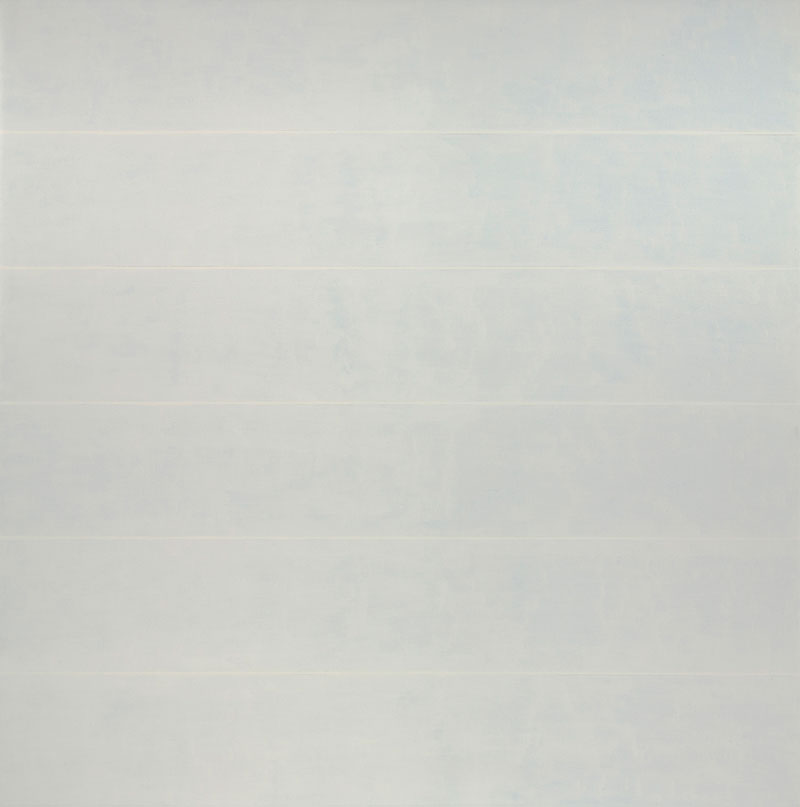

c. 1993-1994, acrylic on linen, 60 1/16 in. x 60 1/16 in., Gift of the Artist.

Photograph: © Collection of the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico

The life of an artist is inspired, self sufficient and independent (unrelated to society).

The direction of attention of an artist is towards mind in order to be aware of inspiration.

Following inspiration life unfolds free of any influence.

Finally the artist recognizes himself in the work and is happy and contented. Nothing else will satisfy him.

An artist’s life is an unconventional life. It leads away from the example of the past.

It struggles painfully against its own conditioning. It appears to rebel but in reality it is an inspired way of life.

—Agnes Martin, ‘Advice to Young Artists’

Agnes’ artistic process was exacting—she would sit, often for days or even weeks at a time, in her rocking chair awaiting her muse and mentor, inspiration. The image of a painting, fully formed, would then materialize in her mind and thus, she would extrapolate it using complicated mathematics to arrive at the dimensions of an actual canvas. If she was unhappy with the results, she would not think twice about destroying it. Excellence was her goal and she was not afraid to sacrifice everything in order to achieve her vision of minimalist perfection.

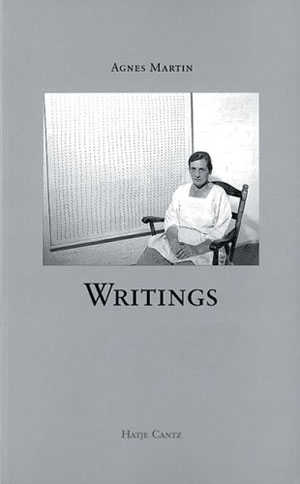

Around this time, despite living the life of a recluse, she embarked upon a series of public lectures, many of which are collected in Writings, delivered in the same manner as she presented her art—succinct, enigmatic, profound—imbued with the metaphysics of Eastern philosophy and pointing to a place uncontaminated by contemporaneous concepts of art theory and practice. For Agnes, the life of an artist was a means to freeing oneself from all fear and confabulation of ordinary existence and, instead, seeking to embrace the joy and beauty of living a truly authentic life.

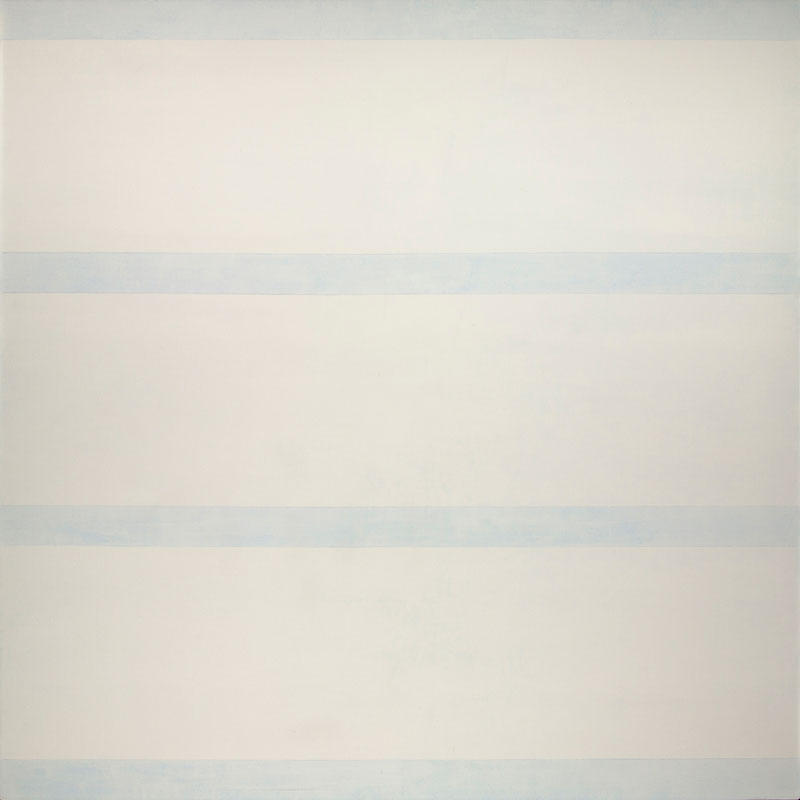

c. 1993-1994, acrylic on linen, 60 1/16 in. x 60 1/16 in., Gift of the Artist.

Photograph: © Collection of the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico

My interest is in experience that is wordless and silent, and in the fact that this experience can be expressed for me in art work which is also wordless and silent. It is really wonderful to contemplate the experience and the works. I am sure there will always be some who make this response who will want to try to express it graphically.

But with regard to the inner life of each of us it may be of great significance. If we can perceive ourselves in the work—not the work but ourselves when viewing the work then the work is important. If we can know our response, see in ourselves what we have received from a work, that is the way to the understanding of truth and all beauty.

We cannot understand the process of life—that is everything that happens to everyone. But we can know the truth by seeing ourselves, by seeing the response to the work in ourselves.

Those who depend upon the intellect are the many. Those who depend upon perception alone are the few.

We perceive—We see. We see with our eyes and we see with our minds. We want to see the truth about life and all of beauty.

Both are a great mystery to us.

—Agnes Martin, ‘The Still and Silent in Art’

Similar to Georgia O’Keeffe who painted the exact same door of her adobe homestead over and over and over again, Agnes too, on the surface, appears to repeat the execution of a specific idea when viewed from an intellectual perspective. And yet, just like her fellow New Mexican artist, she sought to penetrate through the walls of mental construction in order to perceive more subtle foundations of underlying feeling, each attempt a unique contemplation upon the creative act.

Indeed, what abstract painting enabled her to achieve was the depiction of pure emotion—akin perhaps to the Forms of Plato—whereby her art was a conduit to the most fundamental of human sentiments: innocence; happiness; friendship; love. Moreover, the homogeneousness of her compositions effectively constituted a pictorial mantra, a relentless pulsation of colour, each painting penetrating deep unto the nature of things, provoking within us an apperception of truth and beauty, and ultimately, our very own inner selves.

c. 1993-1994, acrylic on linen, 60 1/16 in. x 60 1/16 in., Gift of the Artist.

Photograph: © Collection of the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico

We are in the midst of reality responding with joy. It is an absolutely satisfying experience but extremely elusive. It is elusive because we must recognize so many other things at the same time.

The memory of past moments of joy leads us on. The responses of happiness and joy are our first concern.

Works of art have successfully represented our response to reality from the beginning. The artist tries to live in a way that will make greater awareness of the sublimity of reality possible.

Reality, the truth about life and the mystery of beauty are all the same and they are the first concern of everyone.

I want to emphasize the fact that we all have the same concern, but the artist must know exactly what the experience is. He must pursue the truth relentlessly. Once he sees this fact his feet are on the path. If you want to know the truth you will know it.

The manipulation of materials in art work is a result of this state of mind. The artist works by awareness of his own state of mind.

In order to do so he must have a studio, as a retreat and as a place to work. In the studio an artist must have no interruptions from himself or anyone else. Interruptions are disasters. To hold onto the ‘silver cord’, that is the artistic discipline. The artist’s own mind will be all the help he needs.

There will be moving ahead and discoveries made every day. There will be great disappointments and failures in trying to express them. An artist is one who can fail and fail and still go on.

—Agnes Martin, ‘What is Real?’

And herein lies the quintessential raison d’être of Agnes’ life, namely the pursuit of truth through an unflinching commitment to representing joy and happiness by means of the medium of art. Indeed, she lived what she preached and was painting some of her masterworks within the final years of her existence.

Contemporary culture is fascinated with concept, form and content—the work of Agnes Martin, devoid of pride and egoic agenda, takes us away from all manifested phenomena into the realm of emptiness, formlessness, the void. Despite the mental illness that beleaguered her, the clarity of her mind, exhibited so luminescently through both her beautiful prose and paintings, evokes a state of utter transcendence to the transitory nature of life and a return to the reality of what is.

c. 1993-1994, acrylic on linen, 60 1/16 in. x 60 1/16 in., Gift of the Artist.

Photograph: © Collection of the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico

Hold fast to your life, to beauty and happiness and inspiration, and to obedience to inspiration. Do not imitate others or seek advice anywhere except from your own mind. No one can help you. No one knows what your life should be. No one knows what your life or life itself should be because it is in the process of being created.

Life moves according to a growing consciousness of life and is completely unpredictable.

If you live according to human knowledge, according to precept, values and standards, you live in the past.

If you live entirely in the past you will not know beauty or happiness and you will not in fact live.

You must believe in life. Believe that you can know the truth about life.

—Agnes Martin, ‘The Current of the River of Life Moves Us’

Without doubt, Agnes Martin believed in life and loved the very truth she conveyed through her work, distilled so reservedly and yet majestically in a concatenation of cobalt and cyan. She utilized other shapes—triangles, circles, trapezoids—and hues—rosy pinks, pale yellows, warm browns—and yet grids or bands of blue remained a formation to which she returned time and again (cf. Summer, Starlight, Night Sea, The Waves, Falling Blue, Stars), awakening in her, in Kandinsky’s words, a desire for the supernatural.

Indeed, her friend and long-time associate (and founder of the Pace Gallery), Arne Glimcher, revealing in his memoir the final days of Agnes’ life, holding hands in the infirmary of the retirement home surrounded by close friends and family, reminisced that they had sung Blue Skies together (composed by Irving Berlin), being one of her all-time favourite tunes: “Nothing but blue skies / From now on.”

c. 1993-1994, acrylic on linen, 60 1/16 in. x 60 1/16 in., Gift of the Artist.

Photograph: © Collection of the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico

If you have enough respect for yourself you will ask yourself:

‘What am I.’

If the answer is ‘I am a man’ then the question becomes: ‘What is a man.’

When you come to the end of all ideas you will still have no definitive knowledge on the subject. Then you will have to wait for inspiration.

Until you can clear up your true identity you will be tied to a repetition of this life.

I have come to tell you the easiest way to find an answer to this question. First you must say to yourself: ‘I want to live a true life.’ Then you must watch your mind to see the response that it is making to life.

You will discover the true response that you yourself make to life undistorted by the ideas of others.

You will make discoveries every day and they will all be very helpful.

Just as consciousness of the sublime is the path of life so is self-knowledge the path of life.

—Agnes Martin, ‘What We Do Not See If We Do Not See‘

Such was the legacy of Agnes Martin—a visual representation of one woman’s desire to live a true and authentic life against all the odds. Through steadfastly turning her back to the world and embracing an austere and solitary way of living, she found the “silver cord” of artistic discipline and awakened unto a realm of ineffable joy and happiness, peace and love.

And like so many mystics before her whose quest has been the pursuit of discovering the answer to the most fundamental question of all existence, “What am I?”, Agnes faced directly the all-pervasive fear inherent within the human psyche and transmuted it into a personal consciousness of being, a poetic passage of exquisite colour on the path to the threshold of the sublime.

[The photographic images of Agnes Martin’s work have been reproduced with the kind permission

of the curators of the Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico.]

Post Notes

- Agnes Martin Gallery, The Harwood Museum of Art, Taos, New Mexico

- Agnes Martin at the Pace Gallery

- Agnes Martin at Tate Modern

- Mason Currey: Daily Rituals, Women at Work

- Wassily Kandinsky: Sounds

- Paul G. Chandler: The Canvas of Life

- Antony Gormley: Sculpted Space Within and Without

- Rollo May: My Quest for Beauty

- Wassily Kandinsky: Concerning the Spiritual in Art

- Rashid Maxwell: To Save the Planet With a Paintbrush

- Guy Laramée: Fraîcheur

- Mark Rothko: The Artist’s Reality

- Nicholas Roerich: Beautiful Unity

- Albert Camus: Jonas or The Artist at Work

- Hannah Peschar Sculpture Garden & Zen Master Ryokan

- Rupert Spira: A Meditation on I Am