Life imitating art

“The human race is the only species to have forgotten that the whole purpose of life,

the whole meaning of existence, is to have fun, to have pleasure.”

KNOWN FOR HIS minimalistic portrayal of provincial Persian culture, Abbas Kiarostami (22nd June 1940–4th July 2016) produced some of the most beautiful films in contemporary cinema—the Koker trilogy, Close-Up, The Wind Will Carry Us and Taste of Cherry—drawing comparison with other auteurs, namely Robert Bresson, Jean Cocteau, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Andrei Tarkovsky, Nuri Bilge Ceylan and Béla Tarr, who were all similarly preoccupied with timeless narratives encapsulated within transcendental motifs.

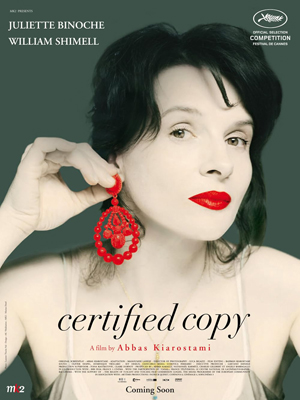

In one of only two films that Kiarostami made outside his native Iran (the other being Like Someone in Love, shot in Japan), Certified Copy is set in the small Italian village of Lucignano and features a philosophically pedantic British writer, James Miller (played by baritone opera singer William Shimell) and an emotionally volatile French antiques dealer, Elle (played by Juliette Binoche, who won the Best Actress award at the Cannes Film Festival in 2010 for her outstanding performance).

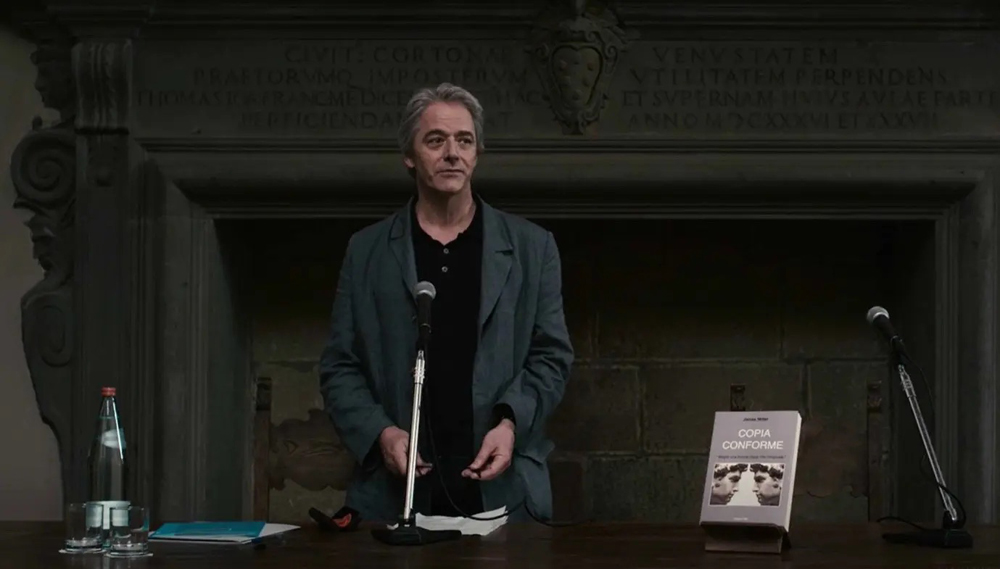

Kiarostami immediately sets the underlying theme for this exquisitely understated movie by having Miller give an opening lecture on his latest book, Copia Conforme, to a small Tuscan audience, wherein he outlines his theories on art, conceding it is “not an easy subject to write about, there are no fixed points of reference, no immutable truths to fall back on.”

The writer goes on to explore the psychological and philosophical aspects of creativity, not least the titular issue of whether an artistic facsimile has any intrinsic value of its own, echoing questions surrounding originality and the difference between the false and the genuine that have existed since time immemorial. Indeed, in a contemporaneous interview with the director, Kiarostami reiterates his cinematic message, believing that a copy has its own innate worth, as most original works of art are only available to a privileged handful of people. Copies, he says, allow for engagement with the common man and, thus, are a means of certification of the original’s inherent design.

On the specific theme of portraiture, issues pertaining to authenticity are similarly explored. Even if a portrait is a so-called original, isn’t it essentially still a copy of the actual sitter? In the manner of Plato’s forms, a physical canvas can only ever be, in reality, a copy of a corporeal entity, with any subsequent copy, therefore, being merely a copy of a copy, so to speak—a refracted duplicate in a hall of mirrors, replicating itself into an infinite regress.

This particular point is exemplified by the principal protagonists when they visit a local museum, where a painting, La Musa Polimnia, is on display. In real life, the portrait of a young Roman woman holding a lyre, which has unknown origins, is housed in Cortona but for the purposes of Kiarostami’s invention, it forms the focus of the Lucignano gallery. Futhermore, in the film, the portrait has recently been discovered to be a fake but is provocatively described in the museum guide as a “real copy—it’s like the Gioconda della Toscana” (a reference to the Mona Lisa in the Louvre, which some art history conspiracy theorists believe to be a copy of the original masterpiece in the possession of the Swiss Mona Lisa Foundation). This invented parable serves only too well Kiarostami’s avowed aim of questioning the real-copy dichotomy of art itself.

Interestingly, Kiarostami weaves his ideas surrounding the nature of art even further into the film’s very own narrative, whereby the characters themselves become entangled in shifting perspectives and alternating levels of truth. Initially, Elle and Miller are presented as strangers but after a waitress in a cafe mistakenly takes the pair for a married couple, they continue to enact such an illusionary arrangement, with Elle projecting onto Miller all her frustrations from her own failed marriage of the past 15 years.

The viewer is then left with a bewildering conundrum as to the ontology of what they are actually watching, its import akin to a scene from Last Year at Marienbad, another masterpiece of psychological drama exposing the veil between reality and dream. Are we witnessing two people pretending they are married or are they in actuality wedded but playing a game of make-believe, portraying that they are strangers meeting for the first time in order to spice up their flagging relationship?

If we return to Miller’s opening prologue, we realize that we have already been prepared for the shapeshifting story, with its reflexive ambiguity and lack of any definitive scope. Some critics have described this aspect of the film to be “persistently baffling, contrived, and often simply bizarre”; however, I wholeheartedly disagree. We must remember that alongside his directorial skills, Kiarostami was also an accomplished photographer and poet and, as such, was able to see the world in a non-linear representation, offering multiple perspectives imbued with uncertainty and the interplay between love and loss. Even the principal protagonists speak in a beguiling melange of English, French and Italian, rendering Certified Copy a triumph of intellectual profundity and literary nuance.

After all, isn’t life itself merely a mystifying, theatrical drama, laced with elusive complexity and lack of any coherent meaning, where our roles and relationships with others are constantly subject to change? When Elle is tussling with her son’s laissez-faire attitude to his homework (and existence itself), Miller acknowledges that only philosophers and children appear to appreciate the transience of life: “We are going to die—so what?” he says, quoting back the son’s nonplussed riposte to his mother. For the right moment is now, Kiarostami is telling us through the opinions of his characters, being alive in the bittersweet flux of awareness, whatever its artistic and relational merits may be.

Post Notes

- Feature image: © Abbas Kiarostami, Certified Copy

- Kiarostami Foundation

- Abbas Kiarostami: 24 Frames

- Alain Resnais: Last Year at Marienbad

- Jean Cocteau: The Art of Cinema

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Cinematic Genius

- Andrei Tarkovsky: Instant Light

- Nuri Bilge Ceylan: Once Upon a Time in Anatolia

- Sergei Parajanov: The Colour of Pomegranates

- Ben Rivers: Two Years at Sea

- Michelangelo Frammartino: Le Quattro Volte

- Bill Viola & Michelangelo: Life Death Rebirth

- Marie Menken: Arabesque for Kenneth Anger

- Gabriel Rosenstock & Ron Rosenstock: Haiku Enlightenment

- The Culturium uses affiliate marketing links via the Amazon Associates Programme